Animals Are Our Neighbors in Cities and Suburbs, Not Pests

With a little knowledge, we can learn to coexist with the coyote in the backyard or the turkey walking down the street

HEATHER TSETSI never usually let her dog, Lily, into the yard unsupervised. But one cloudy spring afternoon in 2009, she made an exception. She darted inside to grab something from upstairs, and when she returned, her large black standard poodle was signaling to be let in. Surprised, Tsetsi opened the screen door, and Lily walked calmly inside. As soon as she closed the door, Tsetsi recalls, she saw "something tan" walk right by her house.

That something tan was a coyote, living in the very center of Atlanta, Georgia. Over the next few years, Tsetsi and her neighbor Tisha Titus realized the coyote was denning between their lots, in a small overgrown space enclosed by their back fences and a train line. They took to calling her Wylie (as in Looney Tunes' Wile E. Coyote). She clearly lived there as much as they did. Titus would pull into her driveway to find Wylie sunning herself on the concrete. "She would always stop and acknowledge my existence. But there wasn't any fear. It was just kind of like, 'Hey, I see you up there. I smell you,'" she says. Wylie ate figs off their trees and shared space peacefully with the neighborhood cat, a 16-pound butterball named Ginger.

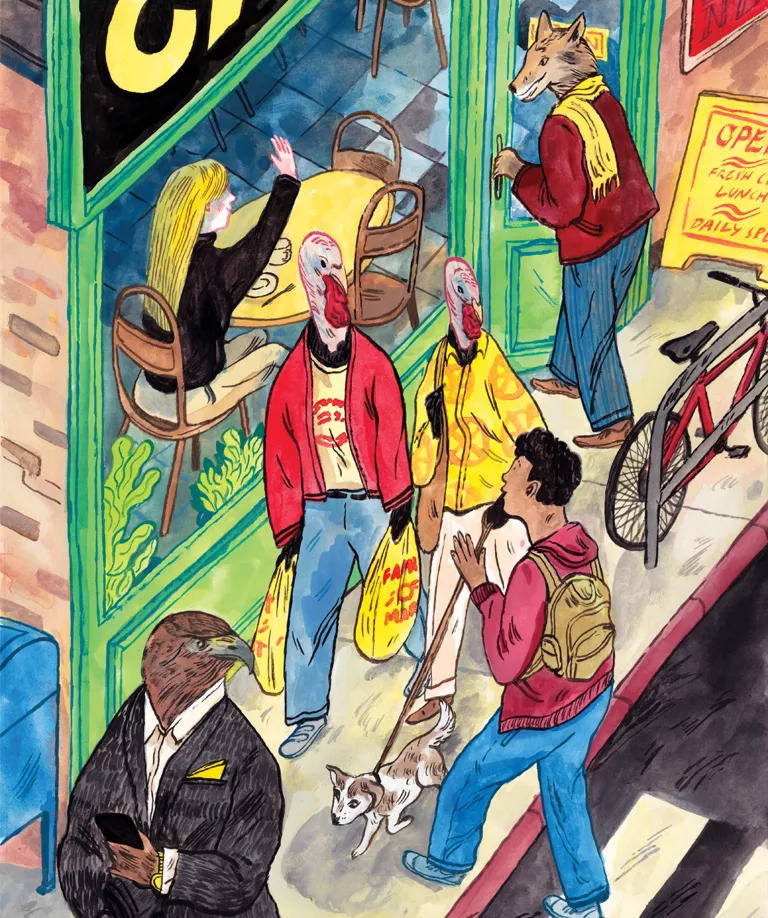

As we humans alter our ecosystems, we also create opportunities for animals. Organisms that benefit from human proximity are called synanthropes. It is easy to picture animals thriving off our trash: urban rats and pigeons, or seagulls by the boardwalk. But those animals represent just one part of the anthropogenic ecosystem. The trash-eating synanthropes often form the base of a food web that feeds less obvious neighbors, such as red-tailed hawks flying over Manhattan. Other synanthropes like suburban turkeys thrive where human activity eliminates the predators that may cause their rural counterparts to struggle.

People are happy to see some of these animals—they are a sign that perhaps we haven't completely failed our wild neighbors. Many people move to suburbs or beyond to feel closer to the land, to get easy selfies with spring wildflowers, to grow or hunt their own food, or just to feel the quiet thrill of finding a fawn curled up in the forest. But when deer munch on our gardens, beavers dam up streams and flood our yards, turkeys attack, and coyotes dine on unleashed chihuahuas, suddenly nature is not so charming. In our human-centered daily lives, it's often easy to forget that nature is all around us, no matter where we live.

Forgetting synanthropes are out there has consequences—for them and for us. It means we react to their sudden appearance with surprise, and sometimes with panic. We light up group texts and Nextdoor because we are shocked to find that the nature we live with is not actually the nature we want, and it's not behaving in the way we expect. We set out birdseed to attract orioles and finches but get angry when squirrels show up instead. We put out poison to rid ourselves of rats and find to our dismay that hawks are poisoned in turn.

Our suburbs and cities are not for us alone, and neither are the gardens, buildings, bridges, and trash cans we build. They are also for our synanthropes. Acknowledging that we alter ecosystems is only the first step. The next is creating coexistence. If we want our synanthropes to succeed, the solution won't be about which animals we deliberately feed, or which populations we promote or control. Instead, coexistence requires accepting our synanthropic ecosystem and understanding what aspects of our own lives benefit—or harm—other species.

"GENERALLY, when you take a species that's uncommon and introduce it, the last thing you're really worried about is it becoming overabundant," says David Scarpitti, a wildlife biologist in the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. And yet, that's exactly what's happening with wild turkeys.

When Europeans colonized the Northeast, they came with a taste for turkey legs and a love of cutting down forests. By the end of World War II, wild turkeys were almost completely gone from their natural ranges in the Midwest and eastern United States. But people still wanted to see and hunt the big, beautiful birds. Over the past 120 years, Scarpitti says, there have been various attempts to reintroduce turkeys.

Success finally came with the trapping and rerelease of some of the last remaining wild birds. The recovery of the turkey, says Michael Chamberlain, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Georgia, "is one of the most dramatic examples of a conservation success story, because turkey populations just exploded."

Turkeys are thriving in urban areas and in the suburbs, parading through the busy streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and across the campus of Harvard University. Their claws click on as much asphalt as dirt. The big birds might take shelter next to wooded running trails or in parks and feed on a mixed diet of wild food and human-provided birdseed. Turkeys prosper where houses have large enough lots to create habitat but where people aren't always rushing back and forth in force.

Perhaps the wild turkeys upending the human-animal pecking order have gotten a little too bold.

Yet even as turkeys are excelling in urban areas, they are declining in wilder ecosystems. Chamberlain has documented an 18 to 20 percent decrease in wild turkey populations. No one knows why. It could be because of habitat loss, predators like raccoons, climate change, or a little bit of all three.

There are several possibilities as to why they might be thriving in the suburbs. Birdseed and fruit from trees are as good for turkeys as they are for chickadees, Scarpitti notes. The presence of large numbers of people keep natural predators at bay, and human hunters aren't allowed in residential neighborhoods, making them safe spaces for turkeys to grow bold.

That boldness, unfortunately, is making the birds less than welcome. A rafter of turkeys at NASA's Ames Research Center in California sent astrophysicists scuttling. They have attacked postal workers. One wild turkey haunted a popular trail in Washington, DC, causing panic and even a little bloodshed. Faced with a fully fluffed-out male turkey standing hip-high, many respond with fear. People have been known to fend them off with sticks, umbrellas, and bicycles.

Fear could be useful, though, if it's the turkeys feeling it. "How could you address some of the issues with suburban turkeys?" Chamberlain says. "You shoot them." As long as people continue to create habitats in which wild animals thrive yet are unwelcome, the most successful animals will be those that are adept at avoiding humans. Chamberlain's research supports the efficacy of using hunting to elicit that behavioral change. In a 2023 study of collared turkeys, he and his colleagues looked at the tracks of turkeys, coyotes, and humans. They showed that after being hunted, turkeys moved away from places where people might access public land and toward private property. Hunt the suburbs, he says, and a little fear could keep turkeys and people apart. It's a technique that is deployed frequently for another overly successful suburban denizen: the white-tailed deer. Many parks, neighborhoods, and even airports now pay for yearly deer culls to reduce population numbers.

Perhaps the wild turkeys upending the human-animal pecking order have gotten a little too bold. But for a city or suburban coyote, having a dash more boldness than that of its rural counterparts might be an important personality trait if the animal wants to make it among humans, says Julie Young, an animal behaviorist at Utah State University.

In a 2019 study of collared coyotes in rural and urban areas, Young and her colleagues showed that rural coyotes were very shy of humans, racing away without looking back when people tried to draw close. Suburban and urban coyotes, however, were more tolerant, particularly when there was good cover they could hide in. The city coyotes were also more willing to explore new objects, another sign of boldness.

A coyote that's too shy, she notes, won't take advantage of food and denning opportunities near humans and may not fare well. On the other hand, eating local pets, or consuming food directly from human hands and nibbling at a finger in the process could get a coyote "lethally removed," Young says.

The middle of the bold bell curve is where the successful suburban coyote lives: just outgoing enough to den and find food among humans but not so much that "you've done something as an animal that people find unacceptable," she says. The ability to pass on these traits may be genetic, or it might simply be learned. Young hopes to do a follow-up study, switching pups from rural litters and city litters to see how their behaviors play out in new environments.

If people accept that the rats that gross them out feed the hawks that they're in awe of, that coyotes live nearby but won't harm them, that they need to watch for turkeys just like they watch for bikes or cars, how differently might they behave?

The line between shy and bold is the one that ensures deer, coyotes, and turkeys won't be seen too often. But confronting overbold turkeys or coyotes in our suburbs—and facing the choice to live and let live, to control, or to cull—is ultimately a question of the kind of environment humans want to create. Can we accept that our suburbs are part of nature? Or are we content to constantly keep the animals we don't want at bay?

IN ATLANTA, Wylie established herself in the sort of place people don't think of as close to nature, unless the nature is rats and squirrels. Wylie didn't seem to mind city living, and her human neighbors, Tsetsi and Titus, didn't seem to mind Wylie. The coyote was a "good" synanthrope. She never touched the cat food or the garbage cans, and she helped rid her neighbors' yards of other synanthropes people love to hate: garden-destroying rabbits and rats.

But in such an urban environment, it seemed like Wylie's dating options were thin. A male coyote would have to cross freeways and industrial corridors just for a date. Then, on Valentine's Day 2014, Tsetsi spotted Wylie in the backyard. She wasn't alone—a male with a distinct reddish cast to his fur was with her. Romance blossomed, and in the spring Wylie and "Valentine" produced a litter of seven puppies. Tsetsi's and Titus's yards quickly became coyote daycare, so they called Chris Mowry, a biologist at Berry College who tracks coyotes in the Atlanta metro area. Mowry put up a camera trap on a maple tree in Titus's backyard and captured photo after photo of pups tumbling, wrestling, and sunning themselves with their mother on a retaining wall.

Mowry's cameras have spotted coyotes everywhere. They're in Grant Park and Piedmont Park. They're playing in the Chattahoochee National Recreation Area and in suburbs like Marietta and Alpharetta. Any kind of green space looks good to a coyote, Mowry says, but ideal spots don't have a lot of human activity.

Wylie seemed more than usually tolerant of being seen by humans. Most urban coyotes will never be seen at all if they can help it, notes Stanley Gehrt, a wildlife ecologist at Ohio State University. He describes urban coyotes as "misanthropic synanthropes." They benefit from being close to people—but they don't have to like it.

In his many years collaring and observing coyotes around Chicago, Gehrt has found that coyotes will eat anything and everything. "One of our coyotes, she knew [when it] was trash night," Gehrt recalls. Another "knew where all the cat colonies were, and it went from colony to colony eating cat food," he says. Coyotes also eat garden vegetables and the rodents who eat seed that has fallen from bird feeders. Cemeteries, especially, can be a good habitat for coyotes, Gehrt says. The green spaces are large and quiet, and some cultures believe in leaving out food for the dead.

The stable access to food means coyotes can easily make more coyotes, as Wylie and Valentine demonstrated. "We've documented higher reproductive rates, and definitely higher survival, in an urban environment," Gehrt says. In a rural area, a coyote pup's chance of surviving its first year of life is only about 33 percent. In Chicago, it's 61 percent. Urban areas like Chicago can even serve as source populations to surrounding rural areas, as young coyotes born in the city wander out to try country life.

If the eating is so good in the city, it might seem strange that coyotes would want to leave. In every litter, however, a few do, spreading out toward the suburbs where the going is a little tougher food-wise but other advantages abound. This is where the misanthropic part comes in. "A raccoon will become a couch potato in one day if you give it enough doughnuts and french fries and stuff," Gehrt says. "Coyotes are much more complicated." In the most dense urban areas, the animals become more nocturnal to avoid human activity. That limits the amount of time they can spend looking for food and defending territory. This balancing act can come at a cost. In a 2023 study, Gehrt and his colleagues showed that the amount of cortisol in coyotes' fur samples—a measure of stress—was higher when they lived in areas with more human development. "You have an animal living in a city with millions of people . . . while still avoiding people," he says. "What other wildlife species has that kind of challenge? Not many."

In New York City, synanthropes like rats, pigeons, squirrels, and sparrows are capable of thriving very close to people, living in human structures and off of human trash. But they are also a food source for another synanthrope, soaring between skyscrapers and nesting under bridges: the red-tailed hawk.

A crew working on the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge recently had to remove a hawk's nest "that was probably 10 years' worth of twigs and bark and plant material," says Sunny Corrao, a biologist with the wildlife unit of New York City Parks. The hawks didn't mind. A pair returned to nest under their newly renovated home, in a slightly different location.

Like the presence of urban turkeys, birds of prey in the five boroughs is a sign of conservation success. As of 2021, 96 hawk nests had been spotted in New York City by the parks department and citizen scientists engaging in a Cornell Lab of Ornithology project called NestWatch. "Birds of prey have started to make a comeback in our environments as we've reduced the use of chemicals such as DDT," Corrao says, and they have now been holding steady for about a decade. Now, she notes, "red-tailed hawks are the most common bird of prey you're going to see in New York City."

Hawks compete with falcons for the bridge real estate but have light towers, sports stadiums, and building ledges to themselves. "We have a new [hawk nest] in a clock tower just right in front of the clock," notes Corrao. These hawks—whose claws are much more used to brick and concrete than branches, and who may never fly over a full-size forest in their entire lives—are the most urban of urban creatures. Red-tailed hawks in particular habituate easily to people and can adapt to a wildly diversified diet, says Justin White, who studies human and environment interactions at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. In his own studies of prey in red-tailed hawk nests, he's found 28 species represented.

Because New York City is home to owls, peregrine falcons, bald eagles, and osprey in addition to hawks, many people have asked Corrao if birds of prey can solve the city's rat problem. Put in enough owl boxes and welcome enough hawks and surely they'd eat all the rats, right? Wrong. "They're not going to make a sizable impact on your rat population," she says. Rats spend so much of their time underground and indoors that even a hawk with a subway card wouldn't make a dent.

And rats aren't always a healthy food source. Among the most common types of rat poison are anticoagulant rodenticides, which cause an animal to die from internal bleeding. Rodenticides can end up sickening or killing hawks that unknowingly prey on poisoned rats. A 2021 study in New York City found rat poison in 89 percent of the 72 sampled red-tailed hawk livers. Later, an estimated 41 percent of the hawks died from ingesting that rodenticide.

According to Corrao, the city's parks department doesn't use rat poison during hawk breeding seasons, and tries to discourage residents from using it as well. Instead, the city is trying snap traps and Rat Ice (essentially dry ice) as well as pumping carbon monoxide into rat burrows, methods that don't harm hawks trying to feed families. It's a constant tightrope walk trying to manage the synanthropes humans don't want—the rats—with the hawks they want to see. This balancing act between the animals we find charismatic and the ones we call pests is made all the more precarious by their connected food web.

SLINKING MOSTLY unseen through cities of millions and thriving off ecosystems that emerged through rapid human planning, not thousands of years of growth and weather, our animal neighbors show an impressive adaptability. Where people thrive, synanthropes will thrive too—whether they're hawks, coyotes, or turkeys. Coexisting with them means acknowledging that they can and do make it in our cities and suburbs sometimes even better than in the wild. Managing them often involves a delicate balance, says Scarpitti, the wildlife biologist in Massachusetts. "We do deal with people on both sides of the spectrum, people who are really frustrated with the presence of turkeys . . . and then there are people who are really interested in it and really find a lot of enjoyment of having turkeys on the property," he says. "It's usually almost split down the middle."

New Yorkers "enjoy seeing raptors in the city because they're typically pleasing," Corrao notes, and people are often surprised to find signs of wildlife in such an urban area. Corrao uses any opportunity to educate residents about how animals can adapt to cities. In Atlanta, Tsetsi and Titus like to teach their neighbors about coyotes when sightings pop up on Facebook, letting residents know that with a healthy amount of respect, coexistence is possible—no culling needed.

Once people get beyond the shock of seeing wildlife where they don't expect it, maybe appreciation could follow. Animals are flexible, and people are too. We humans could learn to change small pieces of our lives to coexist with our nonhuman neighbors. If people accept that the rats that gross them out feed the hawks that they're in awe of, that coyotes live nearby but won't harm them, that they need to watch for turkeys just like they watch for bikes or cars, how differently might they behave?

When Gehrt started studying coyotes in Chicago, he says, "I had preconceived notions about where they could live, where they couldn't live." He thought they'd never make it downtown, in the industrial areas, by the river. "Every time I say they can't do that, you know, after a few years, there are coyotes doing exactly that." Once we recognize the sheer adaptability of city creatures, it's hard not to be impressed. They will be our neighbors whether we want them or not. We might as well try to get along.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club