Is virtual reality a new frontier for environmental communication?

Researchers use VR to simulate what it feels like to be a coral reef living in an acidifying ocean

Photo by zamuruev/iStock

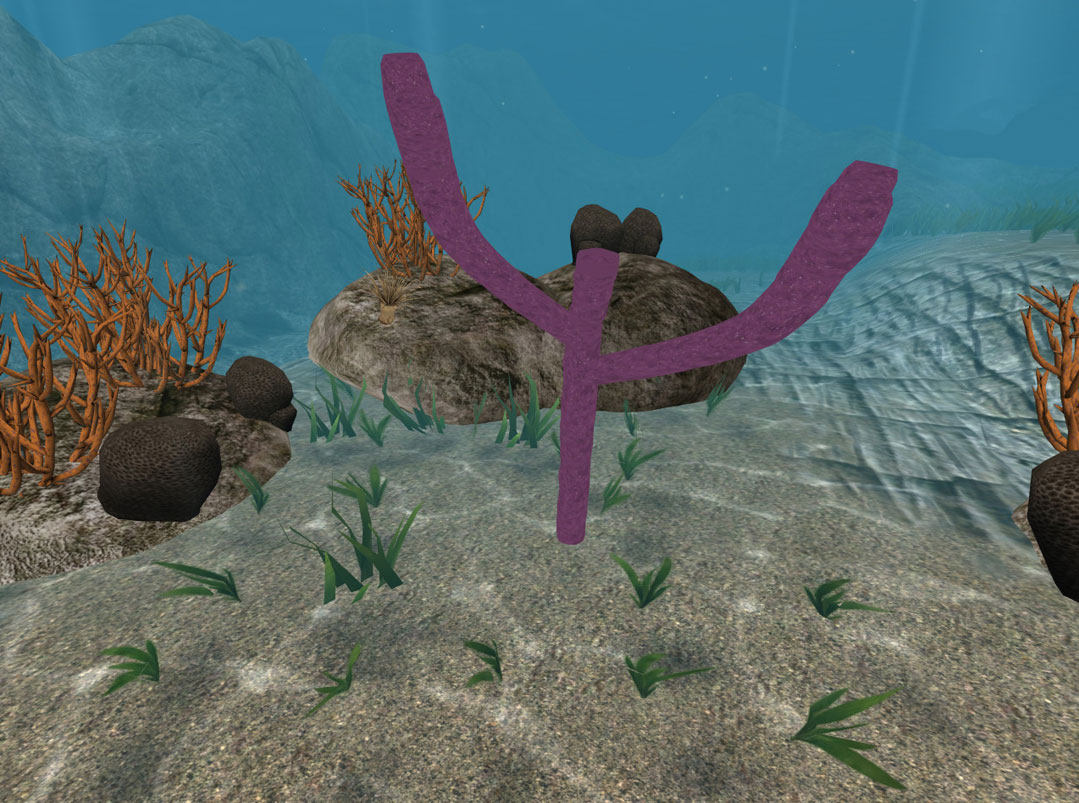

Imagine you are a piece of coral, slowly degrading from the acidification of the ocean you call home. As you gaze at your coral body, you hear a crack and watch as one of your limbs breaks off from the rest of your torso. You are marching to your imminent death, and there’s little you can do.

OK, back to being human. Let’s be honest, picturing what it’s like to be an animal—particularly an unfamiliar one like coral—is pretty darn hard. Environmental communicators are very familiar with this problem. It’s easy to tune out talk of “climate change” and difficult to dish out compassion for animals or plants that you’ve never even seen, especially when celebrity gossip and cat memes compete for our attention. How do we break the pattern of public apathy to increase environmental engagement?

A recent study by a group of researchers from the University of Georgia, the University of Connecticut, and Stanford University suggests a promising new way to heighten such engagement: through virtual reality.

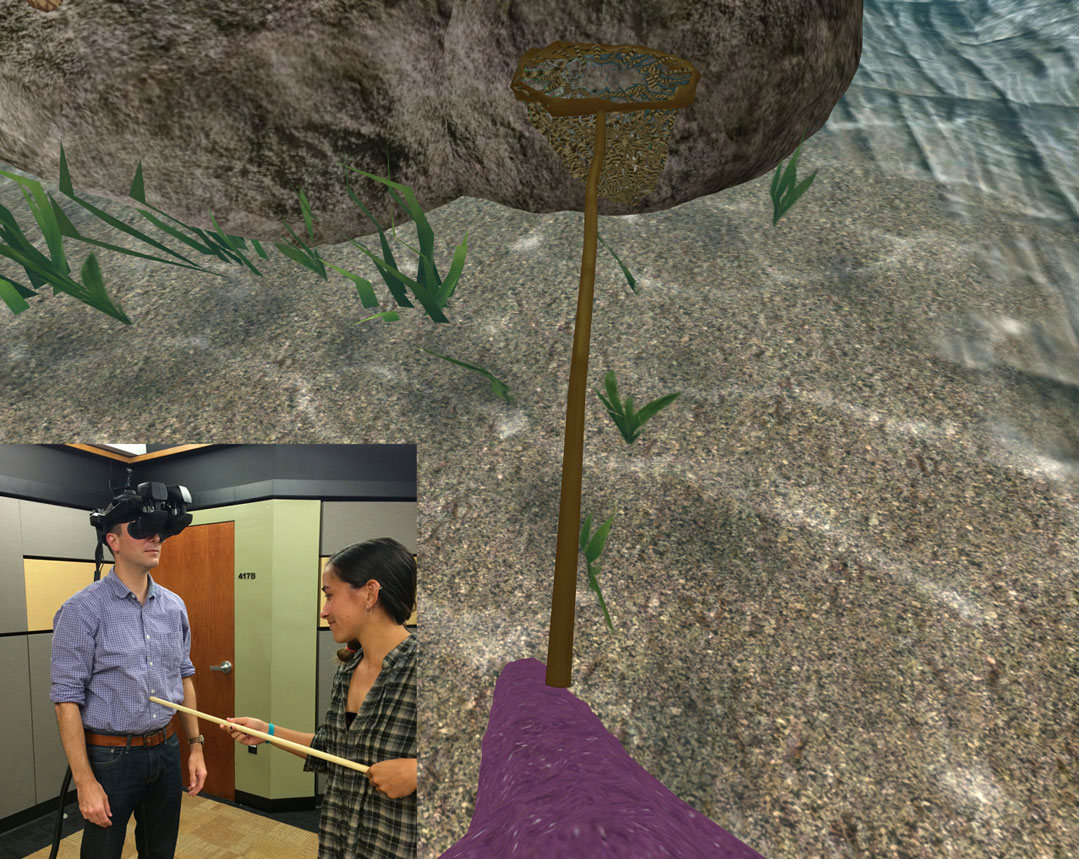

In two separate experiments, subjects wore VR headsets to approximate the experience of—you guessed it—being a piece of coral. That crazy thought experiment above? It’s actually exactly what the subjects lived through while immersed in their virtual experience. To be clear, the subjects didn’t just watch and hear their virtual coral bodies degrade. In order to make the participants also feel a more visceral connection to their virtual selves, researchers induced what they call “body transfer”—a.k.a. tricking the brain into reassociating a virtual body with your own body. They did this by tapping and prodding the participants’ body parts whenever their corresponding virtual body parts touched other virtual objects. The researchers also increased the participants’ spatial presence within the virtual world using spatialized sound and floor vibrations.

Researchers induce "body transfer" by prodding the participants' body parts whenever their corresponding virtual body parts touch other virtual objects. | Photo courtesy of Grace Ahn

Subjects use virtual reality to enter the bodies of coral. | Photo courtesy of Grace Ahn

After five to 10 minutes of such immersion, participants filled out a series of follow-up surveys that measured their overall connection with nature. Their responses were then compared with a control group that merely imagined the scenario in the same way that you did at the beginning of this article. Remarkably, the experiments showed that the participants who spent a few minutes in the immersive virtual environment showed more compassion and active concern for the environment than their control group peers. The effects also lasted for at least one week.

This study follows from a long line of VR studies conducted by Grace Ahn, an assistant professor at the University of Georgia, who began her VR research while earning her PhD in communications at Stanford University. Over the years, Ahn has studied VR in a variety of contexts, including its ability to promote greater interpersonal empathy and better health habits. After reading studies that showed empathy increases among participants who merely thought about the perspectives of birds in an oil spill, for example, Ahn was inspired to apply her work to environmental empathy.

“The original idea for this study actually came about in an earlier study when we looked at whether virtual reality could get you to better understand people with disabilities. We tested this in the context of red-green color-blindness,” Ahn said. “We were really interested in how virtual reality could quite literally put us into the shoes of another person—really experience what it’s like to live as a person with a disability, and we were interested in extending this idea to nonhuman entities.”

Ahn believes that VR has huge potential for informing the public on environmental issues. “There’s a whole bunch of research that shows that environmental behaviors can be influenced by virtual simulations, so I can see a lot of that go into educational contexts.”

To explore this application further, Ahn’s research team will continue conducting follow-up studies on virtual reality’s role in environmental education. “We’re trying to really parse out what type of information is better delivered in virtual reality, because we don’t think that VR is going to be the answer to everything,” she said. “One strength of virtual reality is that it’s able to give you a very vivid experience. That being said . . . I don’t think we can say that virtual reality can completely replace traditional storytelling because experiences, in and of themselves, don’t tell the entire story. You can have a very visceral experience, but you don’t have any context, so in order for people to better understand the experience, there needs to be more information given in a more traditional way.”

Even so, she says, “I do believe that we might be at the cusp of a new revolution. We had the internet revolution 20 years ago, and that really changed the way that we communicated, and then we had the mobile revolution a decade ago. Now I think we are ready for another communication platform, where it’s going to really change and transform the way we currently understand how we communicate.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club