Coal versus Recreation in Utah

Haze from Utah's coal-fired power plants threatens its vibrant outdoor-recreation industry.

A clear view of Balanced Rock in Arches National Park, Utah. | Photo by Whit Richardson

One hand on the wheel, the other clutching a cup of coffee, Ashley Korenblat steers her red Ford pickup into a dirt parking lot at the trailhead of Navajo Rocks, a 19-mile single track in Grand County, Utah, just outside Canyonlands National Park. The figure-eight trail winds through the pinon and juniper highlands above the town of Moab. "It's a huge thrill," she says. "It goes through four or five desert ecosystems—big sections of rolling slickrock, canyons with alcoves, shady parts with plants and springs. From the road, you wouldn't know any of it was there." The trail also boasts classic Utah views: On one side are the sandstone layers of the Book Cliffs. On the other side are the sparkling La Sal Mountains, so named because their distant sprinkling of snow looked, to Spanish explorers, like salt.

Korenblat owns Western Spirit Outfitters in Moab. She's a mountain bike guide with 18 years of experience and is a passionate advocate for the region's growing recreation sector (the baseball cap she wears over her curly cloud of chestnut hair says "Moab #playbabyplay"). As though to illustrate that new economy, two young men drive up in a silver Subaru, hauling a trailer loaded with bright-green Kona bikes. Another car rolls in carrying three more mountain bikers. The five vacationers spill out, strip immodestly out of their road clothes, pour their limbs into shimmering tights and tops, and layer their outfits with shorts and T-shirts.

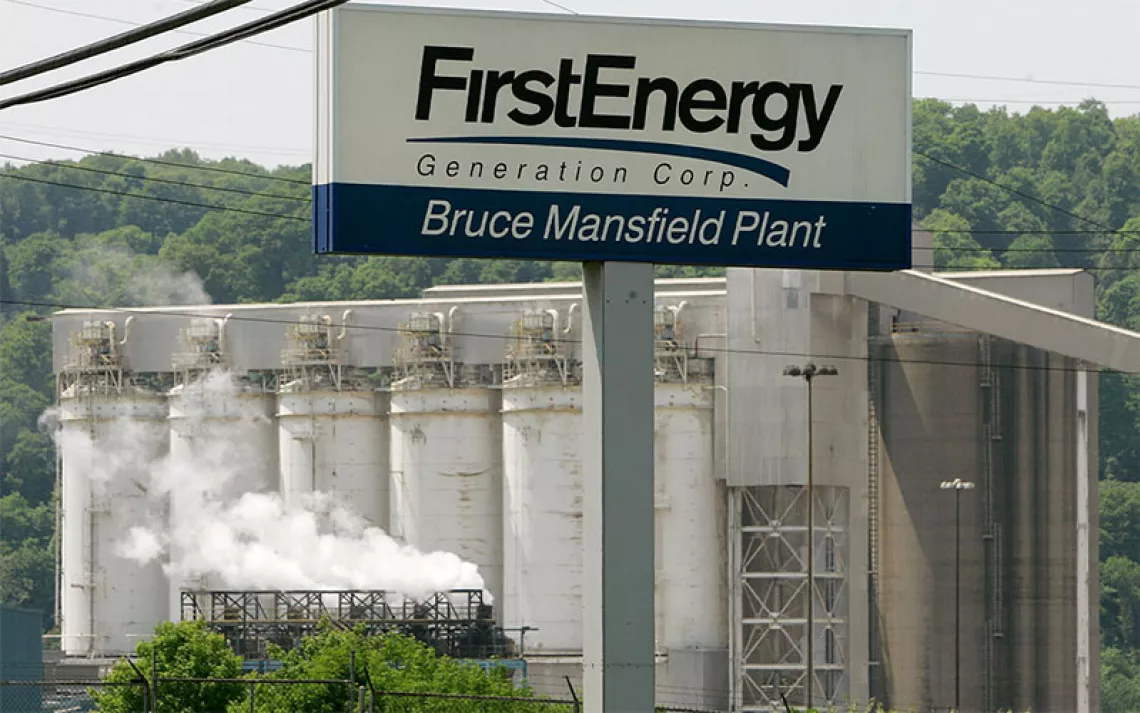

Emissions from PacifiCorp's Huntington coal-fired power plant blow into neighboring national parks in Utah. | Photo by Alyn Johnson

Emissions from PacifiCorp's Huntington coal-fired power plant blow into neighboring national parks in Utah. | Photo by Alyn Johnson

"Where are y'all from?" asks Korenblat, an Arkansas native. She invites them over to view a trail map she unfolds across her truck's tailgate, encourages a nervous beginner, and sends them on their way.

When outsiders think of Utah, they usually picture Korenblat's stomping ground in the southeastern part of the state: redrock cliffs, flood-cut canyons, and improbable arches that sometimes glow green in the snow. But it's the pine-covered Wasatch mountains, cutting through the center of the state, that have defined Utah's economy for more than a century. The Wasatch Range fed and watered Mormon settlers who built their capital on its western front, and provided coal to fuel their industries. A county just east of the mountains is even named for the stuff: It's called Carbon.

Directly south of Carbon County is Emery County, where the Hunter and Huntington coal-fired power plants provide electricity for the half million customers of Rocky Mountain Power, a division of utility giant PacifiCorp. Nearly 400 workers and their families depend on the plants; without them, the small towns of Castle Dale and Huntington might cease to exist.

The plants' pollution, however, drifts south into the five national parks—Arches, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, Canyonlands, and Zion—for which Utah is famous, and which draw some 2.5 million visitors every year.

"The prevailing winds blow emissions from those two coal plants smack into us," says Chris Baird, a former director of the Canyonlands Watershed Council. The resulting haze, says the EPA, cloaks the towering red rocks in a milky film more than 300 days a year.

Moab city councilmember Heila Ershadi has fought to clean up the tourist mecca's increasingly dirty air. | Photo by Whit Richardson

"Every county in Utah has developed according to the assets that it has," Baird says. Emery County has coal; Uinta County has oil and gas. Grand County has a little oil, a little gas, and some potash. But its economic engine mostly depends on its breathtaking geology. "People come here to look at stuff," he says, leaning forward in his chair and running a hand through his tousled brown hair. "They take little walks to viewpoints and want to take pictures. If they can't see what they came to see, that's a big problem."

It is not, however, a new problem. Polluted air has been recognized as an issue at Arches and Canyonlands since at least the 1970s. Back then it was blamed on a uranium-ore processing operation on the outskirts of Moab. The company moved out two decades ago, and the U.S. Department of Energy is cleaning up Moab's old uranium tailings.

But the smog didn't go away, and public officials gradually realized that air pollution wasn't just a local problem. The haze that hung in the air around Arches and Canyonlands, like the haze that once plagued views at Grand Canyon National Park, was coming from somewhere else—to a large degree, from regional coal-burning power plants like Hunter and Huntington.

Ashley Korenblat is a mountain bike guide in Moab, where recreation tourism anchors the local economy. | Photo by Whit Richardson

In 1990, Congress gave the EPA the authority under the Clean Air Act to curb regional haze, even when pollution from one state affects another. The next year, the EPA targeted Arizona's Navajo Generating Station as the culprit behind the Grand Canyon's haze and ordered the plant's owners to install controls for sulfur and soot. It would take years, and many cycles of lawsuits brought by the Sierra Club and other environmental groups, before the EPA extended those orders to other states and folded in other pollutants known to foul the air. Special attention was given to Class I areas like national parks—places preserved, at least in part, for their singular, iconic views. In particular, EPA scientists targeted nitrogen oxides, a class of chemicals that form when the nitrogen burned out of coal (and other fossil fuels) hits the air. In sunlight, nitrogen oxides can turn into ground-level ozone, a major component of smog.

Hunter and Huntington release about 20,000 tons of nitrogen oxides every year. It would be possible to cut that atmospheric load by 90 percent, the EPA says, with a technology called "selective catalytic reduction," which turns nitrogen oxides into benign nitrogen and water. Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming all have plans to adopt this technology; some utilities are in the process of installing it at a few of their plants—including a PacifiCorp plant in Wyoming.

Utah, however, has held out. Four years ago, the state's Department of Environmental Quality submitted a plan to the EPA to mitigate haze that did little to cut emissions of nitrogen oxides from coal plants. The EPA didn't accept the plan and told the state that it had to do better. Utah submitted a new plan in May 2015 that was almost identical to the old one, except that it claimed credit for the recent closure of a tiny coal plant in Carbon County that was a 10th the combined size of Hunter and Huntington.

"The only difference is how Utah is framing its arguments," says Cory MacNulty, senior program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association. "The state's plan does nothing to cut emissions at the Hunter and Huntington facilities. Instead, it takes credit for a plant that is already closed, the Carbon plant. And what's at stake is the air quality at national parks, the communities near those parks, and the people who visit them." That plant had to be shut down anyway, she notes, because it couldn't meet new federal standards for mercury. And closing it didn't help Grand County at all, Baird says: "That wind doesn't even blow in our direction."

Korenblat worries not just about the effects of coal plant exhaust on scenic views but also about what ozone—which is known to exacerbate asthma—does to the lungs of people who live in southeastern Utah or go there to grind up hills, explore slot canyons, run marathons, and scale rock faces. "It's going to be a huge marketing problem," she says, "if it turns out we have an air-quality problem in Moab."

The federal government's health standard for ground-level ozone is 70 parts per billion. The American Lung Association recommends an even stricter limit, 60 to 65 parts per billion, to protect both adults and children. At a monitoring station installed at Island in the Sky, a sheer-walled mesa within Canyonlands, the EPA's "eight-hour average" for ozone—which is figured by calculating the average of the annual fourth-highest daily maximum, measured over three years—came in at 67 parts per billion.

"The suggested mitigation for high ozone is not to exercise," Baird says. "But isn't that what 2.5 million people come through this area every year to do? Isn't that what outdoor recreation is—exercise?"

PacifiCorp and Rocky Mountain Power declined to respond to phone calls and emailed questions, deferring to Utah's Department of Environmental Quality. "A decade of research," the agency's executive director, Alan Matheson, wrote in an email, proves that haze in the national parks of the Colorado Plateau "is not caused by emissions of nitrogen oxides from the coal plants."

That's different from saying that the coal plants don't emit nitrogen oxides, or that those nitrogen oxides don't drift across the state to the Colorado Plateau. The state's own analysis confirms that they do. And everyone agrees that installing nitrogen controls on the plants would significantly reduce those emissions. PacifiCorp and the state dispute only that reducing emissions would improve visibility in the national parks, which is the driving issue behind the haze regulations.

Retrofitting Hunter and Huntington to reduce nitrogen oxides from their smokestacks, Matheson argues, would not pass a cost-benefit analysis. "We can't ask hard-working ratepayers to pay nearly $600 million for no measurable benefit," he writes. "In an age of limited resources, that money could be spent in other ways that generate much more significant benefits to air quality." Forcing PacifiCorp to spend more money on the plants, he suggests, might even backfire, in that it might "result in extending the scheduled depreciation of the power plants and, therefore, their operating life." (Environmentalists dispute the $600 million price tag.)

Clean air is what economists call a "non-market value." It's not a commodity that can be traded and sold. Korenblat can explain to Utah's legislators how mountain biking alone employs 300 people in Grand County, paying out $8.4 million in salaries, while statewide, tourism and recreation contribute $7.5 billion to the economy every year. Baird can explain the cost of the coal plants to public health. (The Clean Air Task Force puts Utah's public health costs from Hunter and Huntington's pollution—measured in asthma attacks, heart disease, and premature deaths—at $200 million.) But, says Moab city councilmember Heila Ershadi, "Whenever I hear the term 'cost-benefit analysis,' I think of a little child with asthma, struggling to breathe."

Ershadi moved to Moab from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, almost 10 years ago. In 2013, she decided to run for the city council "just to shake things up." She handily beat the incumbent. Part of the reason, she says, is that "people wanted a fresh energy" to address the community's environmental problems, which affect not just tourists but also Moab's 5,000 residents. High on that list is the town's increasingly dirty air.

Ershadi, a mother of two, counts among her supporters a young couple, Chad and Margaret Harris, who moved from Salt Lake City because their then-two-year-old son, Wred, had developed asthma. "I wish I could say that moving here made everything better," Margaret says, "but it hasn't." During the family's first weekend in Moab, Wred had an asthma attack so severe that he landed in the hospital.

Margaret knows that coal is not solely responsible for Moab's dirty air and her son's asthma. As Korenblat says, "No one snowflake is responsible for the avalanche." Grand County no longer has its large, polluting minerals plant, but traffic backs up in the national parks (one jam on Memorial Day weekend last year led park officials to suspend visits to Arches), seasonal wildfires fill the air with soot, and in Utah, you can still burn your garbage in the open. Pollen counts are rising as the climate changes, too, further worsening the airborne toxic soup.

While Utah could ban trash fires, there's not much it can do about limiting wildfires or the exhaust from tourists' cars. The coal plants, on the other hand, are "concentrated pollution sources, and ones that we can identify," says Lindsay Beebe of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign in Utah. "Their contribution can be addressed with a specific regulatory solution." Hunter and Huntington contribute 40 percent of the nitrogen oxides that come from Utah's electricity sector; cars and trucks in Grand County emit only a 10th as much.

The EPA has been slow to act on Utah's latest proposal—so slow that last summer the Sierra Club joined with the National Parks Conservation Association and HEAL Utah in a lawsuit to hurry the agency along. Finally, in December, the EPA announced that it would open up the matter to the public and for 60 days solicit comments on two options: approve the state's plan or impose a federally enforceable schedule that would control nitrogen oxides with the best technology on the market. A final decision is expected in June.

Ershadi knows that her best chance at influencing the process is to convey to the EPA what's at stake for Moab and Utah's national parks. Last July, she got a shot at that when Shaun McGrath, the EPA's regional administrator for the southwest states, visited Moab. "I think he saw how special this place is," she says. "I just hope it will matter."

Korenblat, ever the businesswoman, took McGrath out for a bike ride. She presented her own favored solution: Emery County could develop its outdoor recreation economy as Grand County has done. Coal is already on the decline there; PacifiCorp recently closed the Deer Creek Mine, which once supplied Huntington. And Emery County has natural assets to exploit: "It has a world-class bouldering area that people will come year-round to visit, and all kinds of new mountain bike trails in Goblin Valley State Park." Perhaps the county's old exploitive industry sites could become historical curiosities that people will one day come to wonder over, like the old borax mines in Death Valley.

"It won't be an instant transition," Korenblat says, "which is why we have to get started right away. It'll take time to get the word out. But it's real. The recreation economy is real."

WHAT YOU CAN DO

The EPA is considering a final plan to reduce dangerous haze pollution from Rocky Mountain Power's Hunter and Huntington coal-fired power plants. The agency is soliciting public comments on its draft plan until March 14. Please tell the EPA to protect clean air in Utah's national parks and communities.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club