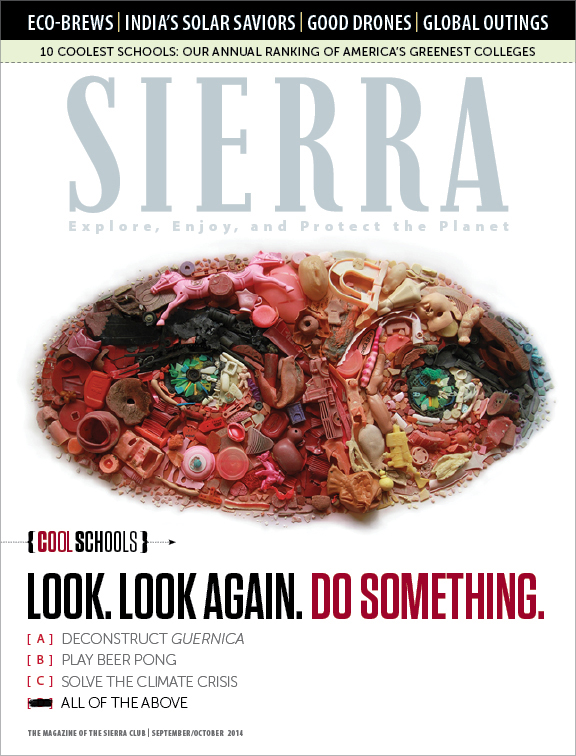

The Finer Side of Flotsam

Pam Longobardi works on Sierra's cover. | Photo courtesy of Pam Longobardi

Pam Longobardi despises her artistic medium of choice. She considers it a global scourge that's both tangibly harmful and potently symbolic of how our runaway consumerism is killing the planet.

Longobardi makes art out of plastic--specifically, out of sea-worn trash that she's hauled from beaches worldwide. She transforms the flotsam into powerful pieces, including the sculpture of two green eyes, at once haunted and accusatory, that stares out from the cover of this issue of Sierra. She calls it Plastic Looks Back, and if you look closely, you'll discover artifacts from her far-flung plastic-hunting expeditions: a fishnet float from Greece, a Hello Kitty head from Alaska, bits of pulverized plastic "sand" from Hawaii, a Virgin Mary from Panama.

While Longobardi considers herself an artist, an archaeologist, an activist, and a laborer, her primary job is as a professor at Georgia State University's Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design, in Atlanta. In her course Art and Environment, she asks students to "look at the triangulation between science, art, and activism in addressing environmental crises."

Like many of the art professors Sierra interviewed for this year's "Cool Schools" issue, which celebrates the artistic side of environmental activism, Longobardi believes that a persuasive piece of eco-art can be an effective tool in the arsenal of social change. (See "A Thousand Words.") "The most sensitive artists are like antennae," she says. "They have a highly attuned visual acuity, so something will come to their attention before the general population is aware of it. They can warn us when bad things are coming."

Plastic's oceanic epidemic first registered on her artistic radar in 2006, when she journeyed to the southernmost point on Hawaii's Big Island and came upon a beach almost entirely covered in detritus that had floated in from distant shores. "I felt like I was looking at a crime scene," she recalls. "Here were these manmade objects that at one time had been useful products, then were forgotten, and then drifted across the entire ocean. And now here it all was, at my feet. So I decided to re-situate it back into a cultural context, to see what it could teach us about the ocean's decline."

Since then, she's made scores of sculptures and installations out of her growing collection of sea trash. Through her Drifter's Project, she has organized the removal of tons of plastic from beaches around the globe, and encouraged locals to turn much of that trash into art. Last year, she won the $50,000 Hudgens Prize, one of the largest cash awards for an artist in North America; the judges wrote that her work "highlights notions of commerce, consumption, and the wastefulness of human society, as well as the powerful and unseen forces of nature to demolish and transform the objects we create."

Despite the success it has brought her, plastic remains her nemesis. Every now and then she turns away from it and goes back to her original passion: painting. "I have to find time to paint," Longobardi says. "Sometimes the plastic just gets to be too much."

Watch a video about Pam Longobardi's Drifter's Project:

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club