The Cost of Coal, Extraction: West Virginia

Mountaintop-removal mines in Appalachia has wiped whole towns from the map.

Mountaintop-removal mines in Appalachia have demolished an estimated 1.4 million acres of forested hills, buried an estimated 2,000 miles of streams, poisoned drinking water, and wiped whole towns from the map.

Lindytown, West Virginia, once home to dozens of families, is now an isolated, lonely place, with only one original family remaining; everyone else sold out to Massey Energy (now Alpha Natural Resources), which was laying waste to a nearby mountain. West of Lindytown, a mountaintop-removal mine caused the population of Blair to fall from 700 in the 1990s to fewer than 50 today, according to the Blair Mountain Heritage Alliance.

Photos by Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

Roger Richmond

Lindytown, West Virginia

Lindytown, West Virginia, was once home to dozens of families, many with roots dating back generations. In 2008, residents started moving away because of a nearby mine. Today, only one original family remains: Roger Richmond and his mother, Quinnie. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

I can remember when I was real young walking through the hall into the kitchen early in the morning and Mom would be at that old cabinet there. She was making biscuits. That's what I'd walk in there for, see if she's got those biscuits made, 'cause I was wanting those biscuits and a couple of strips of bacon to eat. I remember doing that.

We had chickens, pigs. Dad built a pigpen over there. The chicken coop used to sit down there in this corner. Lot of people around here had chickens. We grew a lot of our own basics. Green beans, corn, cucumbers, potatoes, beets, cabbage.

There was houses up and down on both sides up here. After you round this little curve, there was houses on the left-hand side, then there was two on the right. Used to be houses all on up the holler. It used to be pretty bustling, you know. Cars going up and down the road all the time. Kids. Used to have quite a few kids around here.

Quinnie Richmond in front of the home where she now lives with her son, Roger. "I don't think the community will ever be like what it used to be," Roger said. "All the houses that used to be here was built by people that lived in 'em." | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

Sometimes it gets lonely now, a little bit. Momma will be sitting on the couch, and she'll say, "There ain't no more traffic."

Mom, she says a lot of things, like "I want to get out of here." But anytime we go down the road, she wants to turn around and come right back before I even get to where I'm going. I think it's just that Alzheimer's. She'll say, "I got to get home, I got to make phone calls." She can't use the phone no more. Got no idea how to do it.

She tells people she does all kinds of stuff--all the cooking and washing and ironing. Mom does not do none of it anymore. She used to. When she got up, she would start and wouldn't quit till it almost got dark. Either cooking, cleaning, or doing something. Or ironing. Mom always ironed everything. T-shirts. She used to iron her bedsheets. I'm telling you! She wouldn't sleep on a bedsheet unless it was ironed. Now Dad put a stop to it when she tried to iron his undershorts. He said, "You can iron the T-shirts, but you leave them undershorts alone."

Anyway, that's all gone.

I was a miner for about 30 years. I retired when I turned 55. My back's all messed up. I spent most all my time underground.

Quinnie Richmond at home. "Sometimes it gets lonely now, a little bit," her son, Roger Richmond said. "Momma will be sitting on the couch, and she'll say, 'There ain't no more traffic."' | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

Coal is life in this state. My own personal opinion, I know coal has a lot of problems, but I think it would definitely hurt this country if they tried to do away with it right now. Until they get a source that they know can replace it. And I do think mountaintop removal sometimes is the only way to get at it. It's necessary. But I'm not sure that what happened to Lindytown was necessary. Sometimes I wonder if the coal companies couldn't be better stewards in their jobs, in what they do, where they wouldn't have to destroy communities near as much. It makes you wonder whether they could do that or not.

What happened here was the coal company bought everybody out. They decided that to keep from having to pay out a whole lot of money in damages and stuff like that, they'd go ahead and buy as much of it as they could get. Dad didn't want to sell. He didn't want to go through all that movin', all that goin' out lookin' for another place. This was their home, what they'd always been used to. When he passed, he was 87. That was in 2010.

After everybody moved, the coal company tore all the houses down around here, because the vandals just plumb destroyed 'em. Then the company brought a big ol' backhoe in here and tandem trucks, and they loaded 'em all and took 'em out of here. Took everything.

Now when me and Mom go out and come back and I come up this road, particularly after dark, and just see how eerie it is, sometimes it makes you feel sad, you know? I remember back seeing all the houses. Always around the holidays, around Christmastime, come up through here, you'd see practically all the houses lit up with Christmas lights and stuff. Come up through here after dark now, and it's just dark. (Interviewed June 1–2, 2012)

Charles Bella

Blair, West Virginia

"Look up there what it looks like," Charles Bella said of the mountaintop-removal mine near his home in Blair, West Virginia. "It's been 12 years now since that's been reclaimed, and it still looks like a bomb hit it." | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

People think that this mountaintop mining just moves on down the road quickly, but it's not that way. We took out about 14 seams of coal here, and it took six, seven years to do it. No idea how much coal they pulled out. Millions and millions of tons. Somebody made some money. Oh yeah.

From '94 up to '99, it was so dusty around here you couldn't hardly stand it. It got to the point you couldn't sit on your porch. You'd even have to take the pets in the house. And then you had all the noise from the equipment--backup horns, all that--24 hours a day. That was right back there the top of this ridge. It was a manmade hell here.

Bella parked his Ford beside his house the day he got laid off from his last coal mining job in 1999 and hasn't driven it since. "All my work clothes and stuff still's in it," he said. "Ol' greasy coverall and all." | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

My mom and dad, they lived right here beside of me. They put their life savings in their house, and then because of the mountaintop mining, they only enjoyed it for three or four years before they had to pack up and leave. I worked in the mines. I didn't like the underground because I was always afraid of the top fallin'. I worked on the mountaintop mine. That comes back and haunts me to this day. I was part of destroying my own community. (Interviewed May 29, 2012)

Donna Branham

Lenore, West Virginia

"People don't know how hard it is on the Appalachian people," Donna Branham said of mountaintop-removal mining. "They have no idea. And they don't want to know. As long as they don't have to look at it, they can ignore it." | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

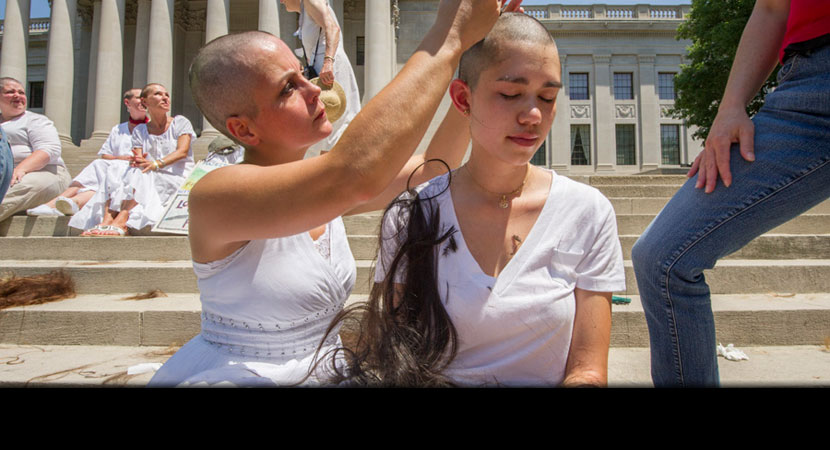

It's a hard decision to take your hair off. It really is, but it's not as hard as watching them destroy my land, watching them destroy my children's future.

I grew up in a coal camp in Scarlet, West Virginia. The load-out for the tipple was like a mile and a half below my home. So I was used to the dust and the noise and the pollution.

My dad worked 39 years at that mine. When he retired, they shut the mine down, and him and my mother thought that they would have a really good life in that community. All of my dad's brothers and sisters--there were 11 of them--lived there. I had grandparents, great-grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, you name it. We all lived there. It was a nice, peaceful way of living.

Well, the same company came back and started stripmining. They let off shots that tore the foundation of my parents' house apart. The chimney pulled away from the house. The roof leaked. Their life was just miserable. The breaking point came one evening when my dad was getting out of the bathtub. It was around 7 in the evening, and they weren't supposed to be blasting after 5 p.m. They let off a big blast and the house shook like there was an earthquake. My dad had a heart attack.

The Branhams met in high school and married shortly thereafter. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

So they ended up selling, which I think was what the mining company wanted anyway. My mom and dad moved, along with my aunts and uncles and everybody. The family just got scattered. My mom made it one year after they moved from Scarlet. And the day she died, I held her head in my lap and she cried for home. She wanted to go home.

They always talk about the cost of coal. I can tell you the true cost of that lump of coal. It cost my family. The only people that get rich are the people that own the coal mines.

When I felt those first streaks of the razor in my hair today, I felt empowered. I felt liberated. It gave me strength. I want the world to know how much it hurts my people. If they would come and live where we live and see what we see, they'd be out there rallying with us. My hair will grow back, but the mountains will not. (Interviewed May 28, 2012)

Hershel Aleshire

Blair, West Virginia

Hershel Aleshire of Blair, West Virginia: "Back when I was a kid, we made our own fun. We fished and we played ball and rode horses. We run after girls. Some of it I ain't gonna tell ya. Turn the camera off, I still ain't gonna tell ya."

I'm not the oldest person in Blair. Alfred Jones is the oldest. He's about 86 or 87. I'm 83. I still drive the four-wheel all the time. Yesterday we rode some 40 miles through the mountains.

"My wife, she died maybe two years ago," Hershel Aleshire said. "We were married 62 years. She was a fine woman. If she'd've had a good man, she'd've been all right." | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

I was born up the road and lived there till I was about eight years old. Then my daddy bought this holler, and I've lived here ever since. Back when I was a kid, we made our own fun. We fished and we played ball and rode horses. We run after girls. Some of it I ain't gonna tell ya. Turn the camera off, I still ain't gonna tell ya. I's kind of mischief when I was young.

Aleshire shares a laugh with his next-door neighbor Carlos Gore. "I'm too old to move now,'' Aleshire said. ''Why would I want to move?" | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

I raised my family right here. My daughter, she lives about 10 miles on down the road. She's got two kids and my son's got two. Great-grandkids, I got five of them. I worked in the mine on a preparation plant for 42 and a quarter years. My daddy got me the job, and I worked with him till he retired. I retired in 1992.

I hate to see 'em destroy the mountains, but I know people's got to work. And I don't know where one balances with the other. Because what they're doing, it'll never be no good anymore. Trees will never grow back. All it'll be is a briar patch. Like I say, I don't know. (Interviewed May 29, 2012)

Marilyn Mullens

Cool Ridge, West Virginia

Tomorrow we're planning an event in Charleston at the West Virginia State Capitol steps, a silent protest, where women from Appalachia will come together to shave our heads. We want to show a solidarity with our mountains that are being stripped, our people that our getting sick. Just to show that we're willing to give up something to get people to pay attention. I grew up in the coalfields in Boone County, in Sand Creek Hollow mostly. Living there, it's coal mining. That's the big industry. So you don't really pay attention if it has any effect on the environment, especially when you're a kid. I moved away and came back in '93. I was busy being a single mom and going to nursing school and doing my military duty.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

Marilyn Mullens organized the Memorial Day protest against mountaintop-removal mining: "We just want people to be aware. Know that every time you turn on a light switch . . . someone here is paying for that with dirty water, with air that they can't breathe." | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

In the late '90s, they started doing mountaintop-removal mining, which is where they just blow the tops off the mountains. They use tons of dynamite. There's dust everywhere. They clearcut the trees. It's just a big mess. Then in 2001 we had a horrible flood in the hollow where I live, and a lot of my friends and neighbors lost their homes. And we all knew that it was because there were no trees or topsoil on the mountain anymore. We knew that was what caused the flood, but according to the coal companies, it was an act of God, because it rained hard.

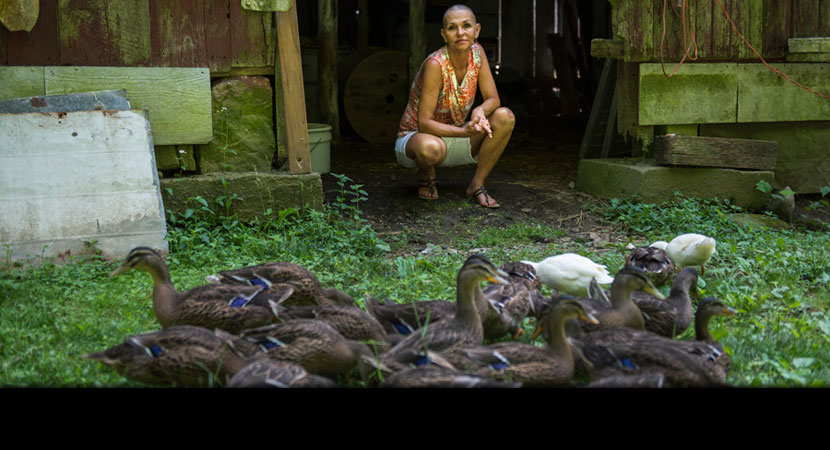

Marilyn Mullens at home in West Virginia, the day before she had her head shaved to protest mountaintop-removal mining. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

In 2004 I was on active duty in California, and my dad called and said my home had come off its foundation. There was a big sinkhole. They were still doing blasting. My house sat for five years before I could sell it, and I had to take a loss. A lot of people don't even have that option. That's there home, that's where they've always been, that's all they have.

When I was growing up, we learned how to garden, we learned how to quilt, we learned how to can and preserve food. That was part of our Appalachian culture. We took care of the land. I think a lot of the women that you're gonna see tomorrow [at the protest], these are the women that don't want to see that destroyed. We want our children to experience West Virginia and Appalachia like we experienced it as children.

Marilyn Mullens, shortly after she had her head shaved to protest mountaintop-removal mining. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

What was it like? It was great. We played in the river, we played in the creeks, we played in the mountains. That was my backyard. I have an uncle, I remember he used to take me to find the fairies, in this little hollow. We'd walk along the railroad tracks and go way back in, and we'd be looking for fairies. And it just looked like a place where fairies would be. It was beautiful--green, with a creek running through it. The little waterfalls that would come off the mountain. We'd gather moss and make our rugs. Pick the dandelions and the plantain and make our salad. It was beautiful.

Marilyn Mullens (left) and Donna Branham on the steps of the West Virginia State Capitol. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

Those mountains are like living beings, and every time I've seen them where they've been blown up, I can just hear 'em screamin'. Just cryin'.

I used to fly home when I was on active-duty military, and every time I'd fly back to West Virginia, every time I'd see those mountains, I'd start crying because I knew I was home. And now I just see destruction from the plane, just mountain after mountain destroyed. How can that be right? It's not. It's just not right. (Interviewed May 27, 2012)

Leo Cook

Bandytown, West Virginia

Cook visits the former meeting hall of Local 8377 of the United Mine Workers of America near his Bandytown, West Virginia, home. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

I grew up in Ducky Fuller holler, right up there on that mountain. I loved it. When I was a kid ... lord, I'd catch crawdads and lizards and go fishin'. You could drink the water out of that creek up there.

The whole top of that mountain was nothing but farming country, where the mine is now. We used to have a tater patch up there. Of course back then we had to raise what we eat. Grew corn, beans. We had cellars that we kept it in. We had chickens and hogs and cows. We hunted every night. Coon huntin' and rabbit huntin' and squirrel huntin'. That's how we had stuff to eat, you know.

We had a big radio—it run on a battery. We listened to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday night, you know. We felt like we was rich. I'd walk off that mountain with a quarter, and I'd see a movie and buy a bag of popcorn. For a quarter. You could buy a pop for a nickel. My dad started out in logging. I'd see him come home in the wintertime and take his pants off and stand 'em up on the floor, 'cause they's frozed. He used to tell me that the timber was so big it'd take two days to cut one tree down with a crosscut saw. Two days. This is the God Almighty truth -- I seen trains go outta here, a flat car'd have one log on it. That's all it'd haul. One log. That's how big they were. I worked for the mining companies for 28 and a half years. Six or seven days a week. I made good money.

"I saw Lindytown disappear," Leo Cook said. "Three people up there that died, and I believe in my soul -- I'll go to my grave believin' this—that aggravation's what caused it."

This mountaintop removal done wrecked West Virginia. Ain't no way these trees are going to grow back. Ain't no way. Might be little pine trees or a little locust tree or grass, but that's it.

My neighbors -- a lot of 'em don't like me fighting the mountaintop removal. They say, "Leo, you got no business getting involved in that." I say, "Well, one of these days you're gonna wish you got involved in it. When it's too late, it's too late."

I got a letter about a month or two ago that they're gonna be blastin' up over there, within a thousand foot of my house. A thousand foot ain't that far away. They haven't tried to buy my place, but I'm a'lookin' for it.

I saw Lindytown disappear, and what happened in Lindytown, it's gonna happen here in Bandytown too. It's gonna happen right here. It's comin'. It's comin'. (Interviewed May 31, 2012)

Paula Swearengin

Glen White, West Virginia

On the steps of the West Virginia State Capitol, Paula Swearengin shears Tori Wong of Virginia. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

When they started stripmining, I can remember my grandfather saying that he'd bag groceries before he'd blow up mountains. He said it was wrong, and he was a coal miner for 45 years. It's all he ever did.

In 2000 my grandpa died and my grandmother started getting sick, so I decided to take my boys back to West Virginia. I noticed things weren't right. A little girl next door had a rare form of bone cancer. There was a little boy, 14, dying of kidney failure. One day I was a working single mom, and the next day I was standing on mountains screaming at people.

Paula Swearengin blow-dries her hair one last time before having her head shaved to protest mountaintop-removal mining. | Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

I am a coal miner's daughter. I am a coal miner's granddaughter. But I am also a mother, and there's no way you can justify poisoning my children. My children have just as much right to a future, and just as much right to enjoy these mountains and the beauty of these mountains, as I did. And I will fight to my death for that. Watch out, King Coal, because here come the Queens of Appalachia. (Interviewed May 28, 2012)

THE COST OF COAL

Videos | Photo Gallery | West Virginia | Michigan | Nevada

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club