by Felice Pace, North Group Water Chair

As groundwater planning to comply with the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act gets underway in high and moderate priority basins across California, a new threat to stream ecosystems has emerged. Known as “Replenishment,” water planners believe that declining groundwater levels and related land subsidence due to over-extraction of groundwater (mostly for irrigation) can be reversed by diverting high winter and springtime streamflow to groundwater storage. The State Water Resources Board has already funded projects to divert high flows to replenish groundwater, including in a major Klamath River tributary, the Scott River Basin.

The Scott River is now dewatered even in years of “average” precipitation as a result of unregulated groundwater extraction for irrigation

On its face the idea makes sense. Each year billions of gallons of storm and springtime high water flows through our streams to the sea. Diverting some of that water to groundwater storage makes sense and can be done without further damaging stream ecosystems. However, as clearly demonstrated in streams where high flows are blocked by dams, streams grow unhealthy when they are denied naturally high seasonal and storm flows. And so the question arises: how much of a stream's flood and seasonally high (springtime) flows can safely be diverted to groundwater storage without damaging that streams ecosystem and Public Trust resources, including fisheries?

There is only one way to find out: Scientifically robust flow assessments can determinate how much water must remain in a streams during each month or season of the year. That amount of streamflow will also vary by water year type, including very dry to very wet water year types.

Assessing year around streamflow needs

Beginning in 1982, the California Legislature has mandated that the California Department of Fish & Wildlife prepare flow assessments for California streams and transmit those assessments to the State Water Board for use in evaluating new proposals to divert streamflow for irrigation or storage, including groundwater storage (see the California Public Resource Code at this link). However, so far Cal Fish & Wildlife has completed flow assessments for only a handful of California streams.

Meanwhile, the Department of Water Resources is encouraging local agencies tasked with completing SGMA compliant groundwater management plans, the Groundwater Sustainable Agencies or GSAs, to consider replenishing groundwater by diverting high winter and spring flows to groundwater storage. Here's the link to DWR's report on “Water Available for Replenishment” and here's the link to that agency's guidance for GSA's on how to determine the amount of high winter and spring flows that can be safely diverted for groundwater storage.

Surface flows are not the only water that can be used to recharge groundwater: Water conservation, recycled water, desalination water and transfers of water from one jurisdiction to another are also potential sources for groundwater recharge. High winter and spring streamflows, however, represent the largest potential source of “new” water for groundwater replenishment and it is those flows which water agency and GSAs will most likely target. A rush to appropriate storm and seasonally high streamflows for groundwater storage and subsequent irrigation is already underway and is likely to accelerate in coming years.

Unfortunately, while DWR discusses streamflow needs in its “Replenishment” white paper and in that paper's guidance to GSA's, those documents do not even mention DFW's flow assessments and do not clearly state that year-around flow needs must be determined prior to appropriating storm and seasonally high flows for groundwater storage. Furthermore, DWR's admits in the white paper that its estimates of “Water Available for Replenishment”:

“...may not fully capture competing needs associated with instream flows to support habitat, species (including endangered or threatened species), water quality, and recreation.”

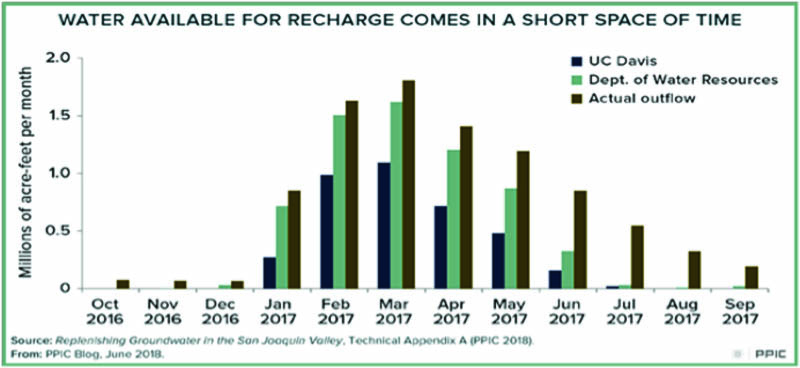

Because it ignores streamflow needs, DWR's estimates of the amounts of water available for diversion to groundwater storage in each of California's regions is clearly a gross overestimation. That should be of great concern to those who care about stream ecosystems. The graph below highlights that concern by comparing DFW's estimates to those made independently by UC Davis scientists.

By creating unrealistically high estimates of the amount of surface water available to recharge groundwater, and by ignoring DFW's instream flow assessments, DWR has created the expectation that California's declining groundwater can be reversed by appropriating seasonally high springtime and storm streamflow. As a result, stream advocates will likely face a flood of new water right applications that ignore or inadequately assess the need for seasonally high and storm flows in California's streams. And that is one among several reasons Northcoast advocates for healthy streams should participate in groundwater management plans currently being developed for Eel River and Smith River estuary lands as well as for the Scott and Shasta Valleys. Only the direct involvement of stream advocates will assure that year-around flows, including high storm and springtime flows needed to maintain healthy stream ecosystems, are properly assessed and protected.

To learn more about California's Groundwater Replenishment issue see these links:

http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7b1b

To learn more about the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act and how you can participate effectively in local groundwater planning see these links:

https://www.ucsusa.org/global-warming/ca-and-western-states/groundwater-toolkit#.W0eNkBgnb0o

https://www.scienceforconservation.org/assets/downloads/GDEsUnderSGMA.pdf