Rita Harris, among the Sierra Club’s first and longest-tenured environmental justice organizers, retired on October 21 after nearly 20 years with the Club. A native of Memphis, Harris served on the EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council from 1996-2001. In 2011, she received the Sierra Club’s Virginia Ferguson Award, named after the Sierra Club’s first paid employee and given to a staffer “who has demonstrated consistent and exemplary service to the Sierra Club.”

Rita Harris with husband Alex and Sierra Club executive director Michael Brune at 2011 Sierra Club Awards ceremony.

“Rita was a fierce advocate for diversity in the Sierra Club, and she always made her case in a forceful but compassionate and inclusive manner,” says Bob Bingaman, the Club’s National Organizing Director (below, second from left). “There was a time when I could count vocal Sierra Club advocates of diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice on my fingers, and Rita was among the strongest proponents. Her work transformed the Sierra Club. She is loved by the community members and partners she serves in Memphis.”

Sierra Club environmental justice program director Leslie Fields, National Program Director Bob Bingaman, Harris, and senior organizer & longtime environmental justice champion Bill Price.

The Planet spoke with Harris during her last week on the job with the Club:

Planet: You were born and raised in Memphis. Do you think this had an impact on your values and your worldview?

Harris: I grew up in the segregated South, and I remember being taught how to ride the public bus. It was customary for African Americans to ride in the back portion of the bus, although we could sit closer to the front if no whites were present. I lived in a predominantly African American neighborhood and went to an African American school. The bus route I took to and from downtown, or to and from my piano lesson, was taken by only a few whites, so I wasn’t often hassled about where I was sitting. This was the Civil Rights era, and sadly, Memphis is where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. That was a huge blow to our community, and we feel it to this day. It hurt most everyone in Memphis, no matter their race or their culture. I was deeply affected emotionally. So yes, growing up in Memphis was a factor in shaping my view of the world.

Planet: Can you share a little bit about your upbringing?

Harris: My family went to a Baptist church in our neighborhood. I went to Sunday school, sang in the choir, played the piano, and went to vacation bible school. I remember my dad reading bible stories to me when I was very young. My parents always taught my brother and me to help others; especially those who were less fortunate than we were. My upbringing instilled an obligation in me to help those in need. Regarding racism, I was taught to be proud of myself and my people. I distinctly remember my dad telling me the racists were the ones with the problem. He said I should always be the best I could be and not let what others think of me define who I am. I grew up confident and knew without a doubt that my mother and father loved me. I truly believe that at root, people of all races and cultures and ethnicities are very similar; they all want good things for their families and their children.

Planet: What led you to become a community activist?

Harris: Back in 1990 I was hired by a local multi-issue non-profit that was looking for someone to organize a task force around South Africa and anti-apartheid issues, and after working there for a short time I was hired to take on local issues as well. So for many years I was mainly involved in the local scene, networking with other groups and activists around the issues of fair housing, fair banking, and environmental issues. I always kept an eye on South Africa advocacy issues, though, and I traveled to South Africa with three different delegations to explore the political landscape, meet with non-profit organizations there, and research complex political issues of the day. And so as I became more involved with issues in South Africa, I naturally became interested in issues around racism, sexism, and classism, and how they affected political decision-making, both here in the United States and around the globe.

Harris with former Sierra Club president Aaron Mair.

Planet: What was your work prior to joining the Sierra Club?

Harris: I was selected to be part of the EPA’s National Environmental Advisory Council’s subcommittee on enforcement, and I served there in a volunteer capacity from 1996 to 2001 during the administration of Carol Browner. I worked for eight-and-a-half years for the Mid-South Peace & Justice Center in Memphis (MSPJC) – the multi-issue social justice group I mentioned earlier where I was engaged in work around South Africa, environmental justice, fair housing, and fair banking. While working at the MSPJC we began to host brown-bag suppers, with the goal of meeting others who were dealing with environmental concerns in the city and learning about their issues – whether they work for nature centers, parks, water & river groups, or community associations. This brought us together to share stories of our work – challenges as well as success stories.

Planet: What was your first connection with the Sierra Club?

Harris: That ties right in with what I was just describing. The brown-bag gatherings became increasingly popular, and volunteers from the local Chickasaw Group of the Sierra Club were among those who regularly attended. That’s how I became familiar with the Sierra Club. Eventually they offered to buy pizza for everyone instead of having people bring a sack supper. One of the rules was that we were not gathered for the purpose of fundraising or selling tickets; we were simply networking and supporting one another’s work. Needless to say, those of us who participated became fast friends, and we began to voluntarily attend public hearings and community forums to lend our support one another.

Planet: Did you or your community in Memphis have an opinion of the Sierra Club at the time you first starting getting involved with the Chickasaw Group?

Harris: There were no negative views about the Sierra Club that I was aware of, if that’s what you mean. The Chickasaw Group had been around for a while, but it was largely unknown in my community. It was generally thought to be a primarily Caucasian organization that was mainly concerned about forests and trees and oceans and rivers. It surprised me, though, when I was helping the group look for office space in 1999, to find myself explaining the Sierra Club to the building managers and leasing staff I encountered.

Planet: So how did it feel when you made the transition from volunteer to Sierra Club staff that year?

Harris: It was great! I was well known because I’d been a part of hosting the brown-bag suppers, so I was already friendly with several Sierra Club members. There was a strong feeling in the Chickasaw Group that the Sierra Club needed to have a stronger voice in environmental justice issues and support the struggles of community members living near factories and hazardous waste sites. I was ecstatic that I was going to be working on issues that were so viscerally important to so many people—especially low-income communities of color—in Memphis and the Tri-State [greater Memphis] area. I had solid allies within the Sierra Club who worked alongside me every step of the way. It really helped that the Chickasaw Group respected my leadership and the leadership of those communities, and assisted where they were needed or when they were asked. This is a key principle of environmental justice work – respecting communities of color and supporting their leadership – and I have to say, the Chickasaw Group was ahead of the curve.

Planet: Who were some of your role models and mentors in the environmental justice movement?

Harris: In the early 1990s there were several people who greatly influenced my thinking about environmental justice and the approach I have taken to my work over the years: Charles Lee, formerly with the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice and presently Senior Policy Advisor with the EPA; Dr. Robert Bullard (below at center), widely recognized as “the father of environmental justice,” whom I first met when he was at Clark Atlanta University and headed the Environmental Justice Resource Center there; Connie Tucker, the former executive director of the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice; and the Rev. Benjamin Chavis, formerly with the United Church of Christ and the national NAACP.

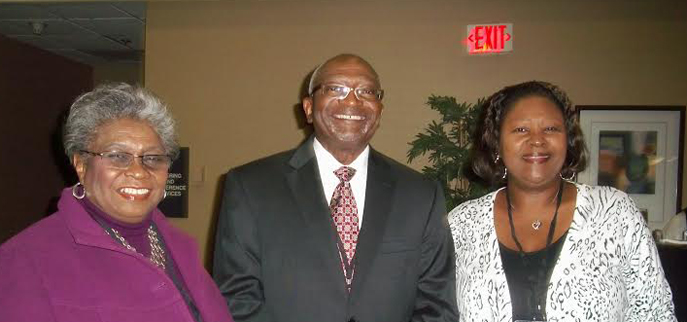

Madeline Taylor, executive director of the Memphis NAACP; Dr. Robert Bullard; and Harris at 2015 Sierra Club Awards ceremony.

Planet: Is environmental injustice still rampant, or has the situation substantially improved over the course of your career?

Harris: We’ve won some important fights and seen some improvement around the country. But even with our successes, what I call “environmental insults” still persist. Many communities that bear the brunt of toxic pollution – EJ communities – have filed Title 6 complaints about ongoing problems of contamination and threats to their health and overall quality of life. Because Title 6 was never applied and enforced as it should have been, many problems still exist. Many improvements have been made here in Memphis, where several large polluting facilities have shut down and the number of “toxic release inventory” sites has sharply decreased.

How much progress we’ve made varies from state to state, the EPA region, and the level of activism in a given community, which is an important way we measure progress. In the current political climate in Washington, we are seeing an effort to weaken the EPA, which will in turn weaken environmental rulemaking and enforcement. If we don’t get back on track, we could see significant backsliding. But that’s where states and municipalities come in; that’s where the real leadership is coming from right now.

Planet: Can you share with us a couple of your most significant victories?

Harris: I guess three in particular come to mind: the final closing of the infamous Velsicol Chemical plant and hazardous-waste incinerator in Memphis; blocking the permit of a company that wanted to start up a nuclear waste incinerator near the Riverview Community along the Mississippi River; and getting the EPA to confirm the existence of hazardous substances in soil and groundwater in Williston, South Carolina, testing of private water wells, and finally getting families on clean, safe city water. And there were of course many other organizing victories that involved supporting community members, empowering them to speak for themselves, and fighting alongside them.

Planet: Why are environmental justice and social justice inextricably linked?

Harris: Environmental justice is measured by our health, the quality of life, and the quality of the environment where we live, work, and play. Low-income communities of color still bear a disproportionate brunt of health impacts from polluting facilities and toxic air and water. Our well-being is directly affected by our surroundings. But environmental injustice is compounded by the way society addresses issues of privilege and the unequal distribution of wealth and opportunity.

Planet: Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the prospects of our society rising up and making a commitment to meeting the challenge of climate change?

Harris: I’m hopeful. I will always be hopeful. The current political leadership cannot remain in power forever. Our job right now is to resist going backward.

Planet: Why is it critical to diversify the Sierra Club and the environmental movement?

Harris: Because it’s crucial to our continued effectiveness. If the Sierra Club wants to be relevant across all segments of society, it must appeal to all segments of society. If the Club wants to be a leader in the environmental justice movement, it should make a commitment to hiring more staff of color, more managers of color, more office and support staff of color, and include them in the planning of initiatives, trainings, events, outings, etc. This in turn will attract more people of color to join the organization. If traditional environmental groups embrace people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds and welcome their perspectives and their leadership, it will enrich the overall environmental movement. The battle against climate change and global warming calls for as many different voices as possible, from all segments of society, fighting together. If we manage to do that, we will win.