By Patricia Hilliard • Executive Committee Member

The Passaic River, which runs from the NJ Highlands, through the Great Swamp to Patterson and down to Newark Bay, was targeted for industrial development as far back as George Washington’s presidency.

It was severely polluted during the industrial revolution of the 1800s. Most of the manufacturing was by small industries such as cotton mills, leather tanneries, cloth dyers, ship builders, and paint and paper manufacturers. In those days, little thought was given to the harm caused by dumping industrial residues into the river.

However, by the 1950s, major modern industries were dumping waste into the river and turning it into a toxic brew. Older residents, who remember a childhood playing near the river, have recalled the dead fish, strange chunks of waste material, and a putrid smell.

The strange colors of the river due to the cloth dying and paint production industries were even stronger evidence of tainted water.

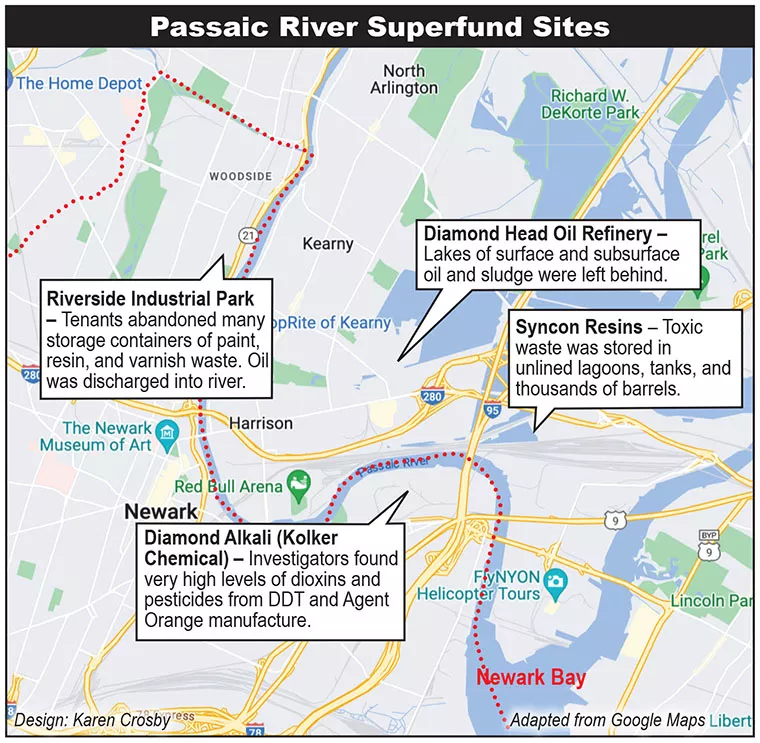

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), as many as 100 industrial facilities within the Lower Passaic River were collectively responsible for discharging contaminants into the river, including dioxins and furans; polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); DDT and other pesticides; and mercury, lead, and other metals.

One of the worst polluters was Kolker Chemical Works, which manufactured DDT. Consumption of DDT-tainted fish by bald eagles and ospreys weakened their ability to produce eggs and chicks. By 1982, there was just one nesting pair of bald eagles left in New Jersey. Kolker Chemical was bought by Diamond Alkali Co., later known as Diamond Shamrock Chemicals Co., which was bought by Occidental Chemical (OxyChem).

Some of the herbicides produced there were used in the manufacture of Agent Orange, which the military used as a “tactical” defoliant during the Vietnam War. These pollutants spread into the soil and groundwater, and, via the Passaic River, they flowed into Newark Bay, New York Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The toxic chemicals drifted into favorite fishing spots, swimming beaches, inlets, and coves. An environmental coalition, including Sierra Club, pushed for legislation to impose wastewater standards that would curtail this pollution. In 1972, amendments to the Federall Water Pollution Control Act (aka the Clean Water Act) caused discharges to the Lower Passaic River to decline, the EPA noted. A small victory was scored.

Focus on Cleaning the Passaic River In 1983, alarmingly high levels of dioxins at the former Kolker plant caused Gov. Thomas Kean to declare a state of emergency. The Newark Farmers Market, a block away, was shut down.

In 1984, the EPA added the site to the Superfund list of high-priority toxic messes. The EPA cleanup plan included construction of containment barriers around the area, soil capping, and installation of a system to reduce the spread of contaminated groundwater.

Studies from 1994 by Tierra Solutions revealed that the toxins had migrated throughout the tidal stretch of the Passaic River, from Patterson to Newark Bay. By 2002, the Army Corps of Engineers and the EPA included a 17.5-mile stretch of the river in their studies. As the magnitude of the pollution became clear, corporations such as Diamond Alkali and Maxus Energy that had contributed to the contamination declared bankruptcy, possibly to escape paying for the damages.

Who Could Be Held Responsible?

In 2004, companies considered responsible for the Passaic River pollution formed the Cooperating Parties Group (CPG), which negotiated with the EPA on a settlement agreement for cleaning up the mess along the 17.5-mile river stretch. By 2007, 70 companies were part of the agreement, although in 2022 a fresh agreement affecting 85 “potentially responsible parties” called for $150 million in corporate dollars to support the ongoing cleanup. The EPA has estimated the total cleanup cost on the lower 8 miles of the river to be $1.4 billion, and the EPA and US Department of Justice have been accused of letting polluters off the hook at the expense of taxpayers.

But Is It Fair?

Recently, the $150 million settlement plan with 85 suspected polluters has been challenged by OxyChem, which owns the former Kolker plant site. OxyChem contends it would have to pay out $441 million for cleaning up the upper nine miles of polluted river and the settlement would allow an almost free ride for other polluters who may be responsible for a significant amount of the pollution.

“Determining how much each company should contribute to the cleanup is an important, serious process,” Charlie Weiss, senior vice president for OxyChem, wrote in an NJ Spotlight News opinion piece October 2022. “If companies…come to believe they can settle cheaply with the EPA with a waiver of future liabilities, what incentive do they have to be honest about the extent of their actions?”

Are OxyChem’s objections to the EPA settlement a tactic to delay cleanup and allow contaminants to disperse so that there are fewer hotspots for it to clean up?

When It’s Not the End

The Passaic River has been polluted for over 150 years. The EPA knows it will take decades before the mess is cleaned up enough to safely swim and fish there again. In the end, those who pay taxes will ultimately pay for the cleanup. Did our society get enough satisfaction from the products manufactured to justify paying for the destruction of our environment? Have we learned any lessons?

Resources

EPA report on Diamond Alkali: https://shorturl.at/cfwCG

State of emergency: https://shorturl.at/wzJRV