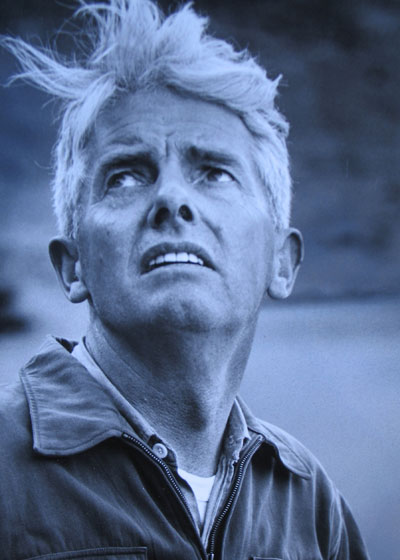

Born in Berkeley, California, in 1912, David Brower joined the Sierra Club in 1933 because of his interest in mountaineering. He had more than 70 first ascents to his credit and served as a lieutenant in the 10th Mountain Division during World War II.

Born in Berkeley, California, in 1912, David Brower joined the Sierra Club in 1933 because of his interest in mountaineering. He had more than 70 first ascents to his credit and served as a lieutenant in the 10th Mountain Division during World War II.

Brower began editing the Sierra Club Bulletin in 1946, managed the Sierra Club annual High Trips from 1947 to 1954, and served as the Club's first executive director from 1952 to 1969. As author John McPhee wrote in his popular 1971 profile, "Encounters With the Archdruid," Brower was the Sierra Club's "leader, its principal strategist, its preeminent fang." He lit a fire under what was then a serene hiking club and later sparked the first flames of other influential organizations, such as the League of Conservation Voters, Friends of the Earth, and Earth Island Institute.

Among his conservation victories: He helped to pass the Wilderness Act and to halt construction of a dam in Dinosaur National Monument. He also helped win protection for Kings Canyon, North Cascades, and Redwood National Parks, along with Point Reyes and Cape Cod National Seashores.

A man of multiple talents, Brower was a master of persuasion. He convinced several generations of idealistic youth, through speeches, images, and the printed word, that saving the earth was an urgent spiritual matter. Legions of young people donned backpacks and headed for the Sierra Nevada after reading On the Loose, a 1967 Sierra Club book Brower published about two brothers coming of age in the wilderness. Thousands more were converted by the stunning details of his nature calendars and big pictorial books. (Both were forms of public persuasion he invented and perfected.)

Millions witnessed his successful crusade to keep dams out of the Grand Canyon, when he famously asked in a New York Times ad, "Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get nearer the ceiling?" And many were captivated by seeing him in person and hearing his "sermon," in which he'd wave a photo of our planet and say, "This is the sudden insight from Apollo. There it is. That's all there is. We see through the eyes of the astronauts how fragile our life is, how thin is the epithelium of the atmosphere."

By the end of the 20th century, Brower was a cultural icon. He'd written three autobiographies, been profiled by dozens of magazines, and been nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize. Among his many awards was the international Blue Planet Prize in 1998, for his contributions to solving global environmental problems.

David Brower died of cancer on November 5, 2000 at 88.