by Lisa DiCaprio

Kate Raworth is a British economist, Senior Associate at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, and Professor of Practice at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. She is the author of Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017). [1]

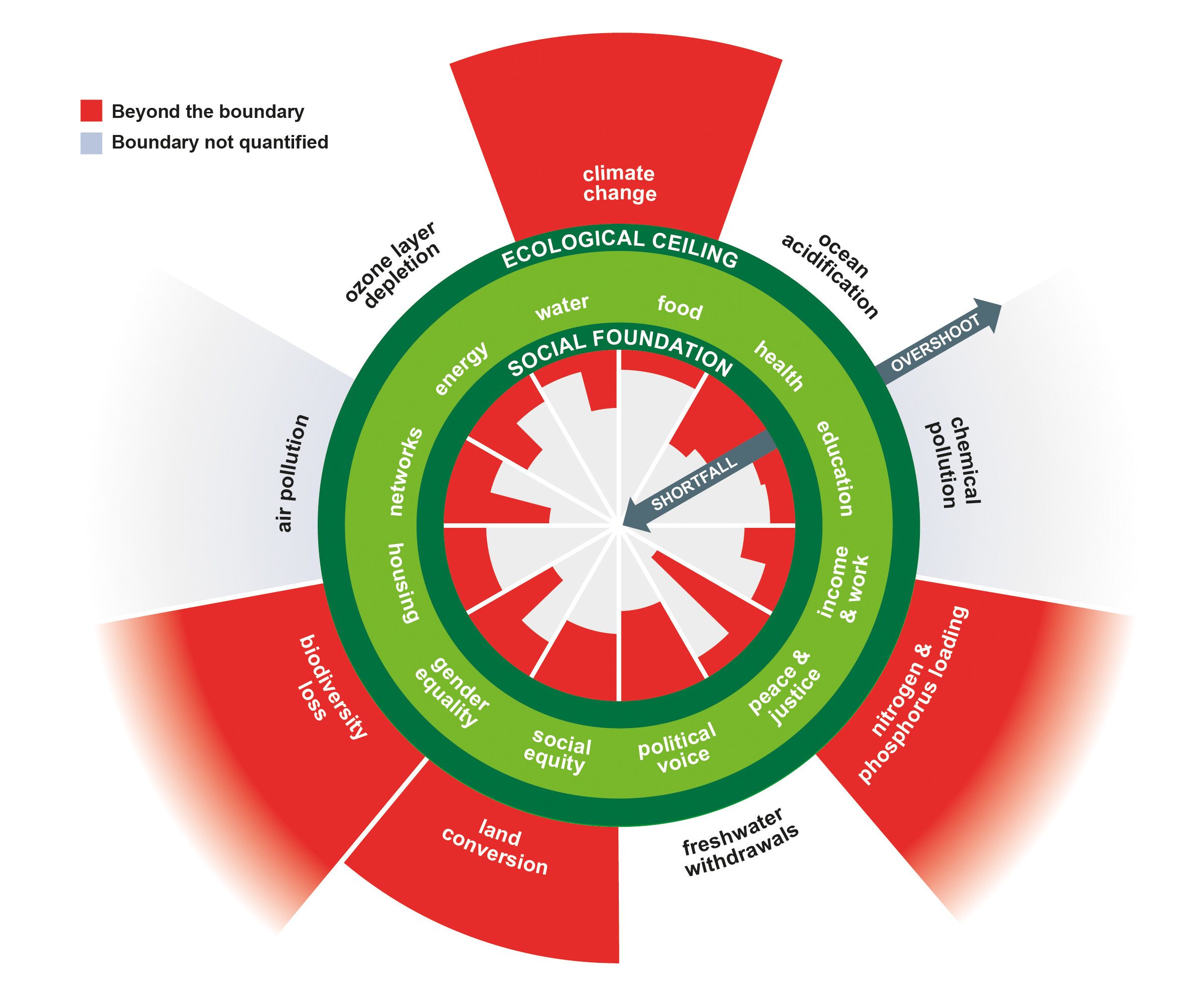

Raworth depicts doughnut economics as the outer ring, inner ring, and the space between the two rings of a doughnut, which she explains in her website article, “What on Earth is the Doughnut?...”:

The environmental ceiling consists of nine planetary boundaries, as set out by Rockstrom et al, beyond which lie unacceptable environmental degradation and potential tipping points in Earth systems. The twelve dimensions of the social foundation are derived from internationally agreed minimum social standards, as identified by the world’s governments in the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. Between social and planetary boundaries lies an environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive.

THE OUTER RING, the ENVIRONMENTAL CEILING, represents the nine planetary boundaries, first identified in 2009 by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. [2] [The Stockholm Resilience Centre subsequently modified three of these original nine boundaries. For the new version, see the Planetary Boundaries website.]

· ocean acidification

· chemical pollution

· nitrogen & phosphorus loading

· freshwater withdrawals

· land conversion

· biodiversity loss

· air pollution

· ozone layer depletion

· climate change.

THE INNER RING, the SOCIAL FOUNDATION is derived from the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which were adopted in 2015. [3] These 12 “essentials of life” are:

· water

· food

· health

· education

· income & work

· peace & justice

· political voice

· social equity

· gender equality

· housing

· networks

· energy

THE SPACE BETWEEN THE TWO RINGS. As Raworth explains in, “What on Earth is the Doughnut?...”: “Between social and planetary boundaries lies an environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive.”

THE EMPTY CENTER OF THE DOUGHNUT is described by Raworth as “a place where people are left falling short on the essentials of life.”

Doughnut economics is informed by the concept of a circular economy, which challenges the conventional linear model of production, consumption, and waste. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “What is the Circular Economy?,” website explains: “A circular economy is based on the principles of designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems.” [4] The circular economy is a form of biomimicry – the imitation of nature, as it imitates the circularity of nature in which everything that dies and decomposes becomes the basis of new life. [5]

Advocates for doughnut economics challenge the growth imperative of traditional economics, which is based on increasing the G.D.P. (Gross Domestic Product), and envision a thriving economy that meets people’s basic needs within our planetary boundaries. [6]

In “What on Earth is the Doughnut?...,” Raworth writes:

Humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend – such as a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer. The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries is a playfully serious approach to framing that challenge, and it acts as a compass for human progress this century.

Amsterdam: a Circular and Doughnut City

On April 8, 2020, Amsterdam became the first city to officially adopt doughnut economics, which was viewed as a guide for a social and economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

Amsterdam’s designation as a doughnut city was preceded by its decision to become a circular city. In 2019 Amsterdam city officials participated in workshops organized by Circle Economy, a locally based Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) partner. The Amsterdam Circular Strategy 2020-2025 commits Amsterdam to a 50% reduction in the use of new raw materials by 2030 and to becoming a fully circular city by 2050. These goals are to be achieved by focusing on three areas: food and organic waste streams, consumer goods, and the built environment.

Subsequently, as related in the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) article, “Amsterdam City Doughnut,” Amsterdam “joined the Thriving Cities Initiative – a collaboration between Biomimicry 3.8, C40 Cities, Circle Economy, and DEAL – to create the Amsterdam City Doughnut portrait,” which was published in March 2020. [7]

This “downscaling” i.e., application of the doughnut economy to a geographical entity, such as a neighborhood, city, region, or nation, began as a collaboration between Kate Raworth and Janine Benyus, the pioneer of biomimicry. [8] As Benyus emphasizes in Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (William Morrow, 1997): “The biomimics are discovering what works in the natural world and, more important, what lasts. After 3.8 billion years of research and development, failures are fossils, and what surrounds us is the secret to survival. The more our world looks and functions like the natural world, the more likely we are to be accepted on this home that is ours, but not ours alone.” [9]

The starting point for the Amsterdam City Doughnut, also referred to as the Amsterdam City Doughnut: A Tool for Transformative Action, was the question: “How can Amsterdam be a home to thriving people, in a thriving place, while respecting the wellbeing of all people, and the health of the whole planet?” This general question was then explored from the perspective of four specific areas:

· Local Social

What would it mean for the

people of Amsterdam to thrive?

· Local Ecological

What would it mean for Amsterdam to

thrive within its natural habitat?

· Global Ecological

What would it mean for Amsterdam to

respect the health of the whole planet?

· Global Social

What would it mean for Amsterdam to

respect the wellbeing of people worldwide?

As Raworth explains in her April 8, 2020 website article, “Introducing the Amsterdam City Doughnut,” “These four questions turn into the four ‘lenses’ of the City Doughnut, producing a new ‘portrait’ of the city from four inter-connected perspectives.”

Highlighting Amsterdam’s significance as the first doughnut city, the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) article, “Amsterdam City Doughnut,” states: “By introducing Doughnut thinking into policymaking, coupled with the self-organising and dynamic uptake of the Doughnut by the city’s civil society through the Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition, Amsterdam has provided an inspirational and pioneering starting point for turning Doughnut Economics into 21st century transformative action.” The Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition, a network of 40 organizations that was formed in 2019, is facilitating the implementation of the Amsterdam City Doughnut.

Amsterdam inspired several cities to officially adopt the doughnut city model, such as Copenhagen in June 2020; Brussels in September 2020; Dunedin, New Zealand in October 2020; and Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada in December 2020. The Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) and its local partners are currently discussing the process for becoming a doughnut city with activists and policymakers in cities and regions throughout the world, including Portland and Philadelphia. [10]

As the “Amsterdam Becoming a Thriving City” section of the Amsterdam City Doughnut emphasizes:

Cities have a unique role and opportunity to shape humanity’s chances of thriving in balance with the living planet this century. As home to 55% of the world’s population, cities account for over 60% of global energy use, and more than 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions, due to the global footprint of the products they import and consume. Without transformative action, cities’ annual demand for Earth’s material resources is set to rise from 40 billion tonnes in 2010 to nearly 90 billion tonnes by 2050. At the same time, cities have immense potential to drive the transformations needed to tackle climate breakdown and ecological collapse, and to do so in ways that are socially just.

Doughnut city initiatives to meet people’s needs within our planetary boundaries are especially important given the conclusions and recommendations of two U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports: Working Group II Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability,” February 2022 [11]; and Working Group III Mitigation of Climate Change, “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change,” April 2022. [12]

In accelerating the transition to a new, green economy, we must reconceptualize the overall purpose of the global economy. As Kate Raworth wrote in her August 12, 2012 Humans and Nature website article, “Doughnut Economics”: “The focus on G.D.P. growth is clearly long past its due date. The global crisis of environmental degradation and extreme human deprivation urgently demands a better starting point for economy theory and policymaking.” [13]

NOTES:

[1] In Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (Chelsea Green Publishing), Kate Raworth devotes a chapter to each of the following seven ways to transition from a 20th- century to a 21st- century economics: “change the goal, see the big picture, nurture human nature, get savvy with systems, design to distribute, create to regenerate, and be agnostic about growth.” Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist was preceded by a February 13, 2012 Oxfam Discussion Paper, “A Safe and Just Place for Humanity: Can we live within the doughnut?,” which Raworth wrote as a Senior Researcher for Oxfam Great Britain. As she states in the Executive Summary, “This Discussion Paper sets out a visual framework for sustainable development – shaped like a doughnut – by combining the concept of planetary boundaries with the complementary concept of social boundaries.” (The Oxfam Discussion Paper was the first time that Raworth visually depicted the doughnut economy.) Raworth also explains her vision of a doughnut economy in a February 10, 2012 oxfaminternational video, “Introducing ‘The Doughnut’ of social and planetary boundaries for development.” (oxfaminternational is the YouTube channel for Oxfam International.) A new edition of Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, which was published in 2022 by Penguin Random House UK, includes Kate Raworth’s “Afterword: Doughnut Economics in Action.” To access a PDF file of the afterward, see the May 22, 2022 Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) posting, Read a new chapter in Doughnut Economics! For a PDF file of the first chapter, which the DEAL Team posted online with permission from Penguin Random House UK see, “Change the Goal: From GDP to the Doughnut.”

[2] In her Oxfam Discussion Paper, “A Safe and Just Place for Humanity: Can we live within the doughnut?,” Kate Raworth explains that the doughnut economy incorporates the concept of nine planetary boundaries outlined in Johan Rockström, Will Steffen, and Jonathan A. Foley’s article, “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity,” which appeared in the September 23, 2009 issue of Nature, volume 461, pages 472–475. Johan Rockström is the Executive Director of the Stockholm University, Stockholm Resilience Centre. For more information on the nine planetary boundaries, see Johan Rockström,’s TEDGlobal 2010 presentation, “Let the environment guide our development,” July 2010 and Johan Rockström and Mattias Klum, Big World, Small Planet: Abundance within Planetary Boundaries (Yale University Press, 2015). See also my article, Lisa DiCaprio, “Ecological Footprints and One Planet Living,” Sierra Atlantic, Fall/Winter 2018. Since 2009 and Kate Raworth’s elaboration of doughnut economics in 2012, the Stockholm Resilience Centre modified three of the original nine boundaries. For the new version, see the Planetary Boundaries website.

[3] See the U.N. website, Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals.

[4] For an overview of the circular economy, see my article, Lisa DiCaprio, “The Circular Economy - Educational Resources (Part I),” Sierra Atlantic, Spring, 2020.

[5] For an overview of biomimicry, see my article, Lisa DiCaprio, “Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature - Educational Resources,” Sierra Atlantic, Fall/Winter, 2019. See also these Biomimicry websites: Biomimicry 3.8 and Biomimicry Institute.

[6] In its critique of the G.D.P. as the measure of an economy’s success, doughnut economics can be viewed as a form of degrowth economics. However, doughnut economics is conceptualized with specific reference to the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the nine planetary boundaries outlined by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. Doughnut economics also avoids the potentially negative connotations associated with degrowth.

[7] For an official description of Amsterdam’s commitment to the circular economy and doughnut economics, see City of Amsterdam, Policy: Circular Economy.

[8] See Kate Raworth’s April 8, 2020 website article, “Introducing the Amsterdam City Doughnut.”

[9] Janine Benyus, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (William Morrow, 1997), p. 3.

[10] For more information on doughnut city initiatives see, for example, Sam Meredith, “Amsterdam bet its post-Covid recovery on ‘doughnut’ economics - more cities are now following suit,” CNBC, March 25, 2021.

[11] See the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability February 28, 2022 press release, “Climate change: a threat to human wellbeing and health of the planet. Taking action now can secure our future,” and report, “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.” See also, Brad Plumer, Raymond Zhong and Lisa Friedman, “Time is Running Out to Avert a Harrowing Future, Climate Panel Warns,” New York Times, February 28, 2022 and Raymond Zhong, “5 Takeaways From the U.N. Report on Climate Hazards,” New York Times, February 28, 2022.

[12] See the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group III Mitigation of Climate Change April 4, 2022 press release, “The evidence is clear: the time for action is now. We can halve emissions by 2030,” and report, “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change.” See also, Brad Plumer, Raymond Zhong, “Stopping Climate Change is Doable, but Time is Short, U.N. Panel Warns,” New York Times, April 4, 2022. For a subsequent report on the unprecedented increase of methane emissions in the atmosphere, which was recorded in 2021 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), see Raymond Zhong, “Methane Emissions, Noxious to Climate, Soared to Record in 2021, Scientists Say,” New York Times, April 7, 2022. See also, Maggie Astor, “Trump Policies Sent U.S. Tumbling in a Climate Ranking,” New York Times, May 31, 2022.

[13] For previous critiques of the G.D.P. see, for example, the writings of Hazel Henderson (1933 – 2022). As Sam Roberts wrote in his May 27, 2022 New York Times obituary, “Hazel Henderson, Groundbreaking Environmentalist, Dies at 89”: “Ridiculing conventional economists – and relishing her reputation in some quarters as a crank – she sought to redefine gross national product as a measure of prosperity not merely to encompass material success on the bases of the cash value of goods and services produced annually, but also to include health, social, educational and other benchmarks that, as Senator Robert F. Kennedy declared in 1968 after being briefed by Ms. Henderson, ‘make life worthwhile.’” Henderson’s publications include The Politics of the Solar Age: Alternatives to Economics (Doubleday/Anchor, 1981) and Ethical Markets: Growing the Green Economy (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2007), which inspired the Ethical Markets TV Series broadcast on PBS. Henderson also popularized the slogan, “Think globally, act locally,” the topic of this 1990 video, “Worth Quoting (Interviews): Hazel Henderson - Think Globally, Act Locally.”

KEY RESOURCES: websites, videos, and articles

Websites on doughnut economics and doughnut city initiatives

- Kate Raworth’s website includes Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) updates, animations, podcasts, videos, events, and blogs.

- Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), co-founded by Kate Raworth and Carlota Sanz, a regenerative economist. [To subscribe to the free newsletter for doughnut economics updates, see: Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) newsletter.]

- The DEAL Team and DEAL’s Advisory Team

- DEAL Community Platform

- Circle Economy

- C40 Cities

- Thriving Cities Initiative (TCI), an aspect of the C40 Knowledge Hub.

- Creating City Portraits: a Methodological Guide from the Thriving Cities Initiative , July 2020.

Amsterdam: Circular Economy and Doughnut City

- City of Amsterdam, Policy: Circular Economy

- Amsterdam Circular Strategy 2020-2025.

- Amsterdam City Doughnut (PDF, 3,4 MB)

- Coöperatie SURF, June 3, 2021, “The journey of the Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition and Sustainable ICT,” Groene Peper webinar, May 27, 2021. [Sustainable ICT refers to sustainable Information and Communications Technology.]

Portland: Doughnut City initiatives

- City of Portland, About the TCI Pilot Project

- On September 26, 2019, the City of Portland hosted the first of three Thriving City Initiative (TCI) workshops with a diverse group of stakeholders.

- City of Portland, September 28, 2019, “Exploring Portland’s City Portrait.”

- City of Portland, September 20, 2020, “How can Portland work toward a thriving recovery from COVID-19?” [Note: “Outcomes of the second Thriving Cities Initiative workshop focused on the concept of using Doughnut Economics to create a thriving city, even amidst a global crisis.”]

- City of Portland, “Portland’s City Portrait.” [Note: “The four lenses of TCI’s City Portrait – social, ecological, local and global – allow local government, community leaders and stakeholders to examine the current state of the city of Portland and create a vision for a thriving place.”]

Copenhagen: Doughnut City

Brussels: Doughnut City

Dunedin, New Zealand: Doughnut City

Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom

- DEAL, “Glasgow’s City Portrait workshops begin.” [The video features “the first City Portrait workshop, which was held with Glasgow City Council staff on 25 April 2022.”]

City of London, England, United Kingdom

- DEAL, London City Portrait and Call to Action

- London Doughnut City Portrait - Edition One.pdf, June 2022.

Websites on topics and initiatives related to doughnut economics:

- European Commission Long-Term Strategy for Climate Neutrality by 2050

- The United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals

- The current nine planetary boundaries outlined by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, which are an updated version of the boundaries first identified by the Stockholm Resilience Centre in 2009.

- Biomimicry 3.8

- Biomimicry Institute

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “What is the Circular Economy?

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Circular cities: thriving, liveable, resilient, which includes several videos.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Circular Example: Shaping a sharing economy: Amsterdam

Videos on doughnut economics:

Kate Raworth videos:

- Kate Raworth, oxfaminternational, February 10, 2012, “Introducing ‘The Doughnut’ of social and planetary boundaries for development.” [oxfaminternational is the YouTube channel for Oxfam International.]

- Kate Raworth, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, October 30, 2017, “Doughnut Economics: How to Think Like a 21st Century Economist.”

- Kate Raworth, TED Talk, June 4, 2018, “A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow.”

- Kate Raworth, Radboud Reflects, June 19, 2018, “Kate Raworth - Doughnut Economics.”

- Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), July 20, 2020, “Downscaling the Doughnut to the City.”

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, December 1, 2020, “Kate Raworth: Building a thriving economy for people within our planetary boundaries, Episode 22.”

- Oikos Denktank, January 29, 2021, “Webinar: Doughnut Economics in practice w/Kate Raworth, Barbara Trachte & Marieke Van Doorninck.”

- Green European Foundation, February 8, 2021, “Doughnut Economy w/ Kate Raworth.”

- Metabolism of Cities, June 23, 2021, “Doughnut Economics in Cities (Podcast with Kate Raworth - DEAL).”

- Kate Raworth, TEDx Talks, December 10, 2021, “How to Live Within the Doughnut.”

- bankingonvalues, December 14, 2021, “The Future of Finance - Dr. Kate Raworth, Economist, Author of Doughnut Economics.”

TransitionTowns, May 13, 2022, “Doughnut economics - Together We Can Summit.”

- Examples of videos posted on the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) website, Tools & Stories section, which is updated on a regular basis.

DEAL, September 23, 2020, “Regenerate Costa Rica and the Doughnut.”

DEAL, November 26, 2020, “Downscaling the Doughnut: what’s cooking in Brussels, Cambridge and Berlin?.” [This was the first DEAL webinar.]

DEAL, March 30, 2022, “Doughnut Cities within a History of Urban Design.” [“Recording of a participatory webinar on the past, present, and future of circular models in urban design.”]

DEAL, “An Indigenous Maori View of Doughnut Economics.” [“Juhi Shareef of Moonshot: City and Teina Boaa-Dean collaborated to reimagine the Doughnut from a Maori worldview.”]

DEAL, June 14, 2022, “Transforming places with the Doughnut: webinar 2.” [“Hear from two local governments working with Doughnut Economics in Brussels, Belgium and Nanaimo, Canada.”]

- BBC REEL, June 29, 2020, “How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy.”

- Ubiquity University, July 25, 2020, “Humanity Rising Day 65: Cities that are Applying the Doughnut Economic Approach.”

Videos on related topics:

- homeproject, “Home,” May 12, 2009 [A film directed by Yann Arthus-Bertrand and narrated by Glenn Close about the story of our human footprint on the planet. See also, homeproject, “HOME - The Adventure with Yann Arthus-Bertrand,” 2009.]

- Ellen MacArthur, TED2015, March 2015, “The surprising thing I learned sailing solo around the world.”

- Janine Benyus, “Biomimicry,” TreeTV, September 11, 2015.

- Janine Benyus, “The Promise of Biomimicry,” TreeTV, January 28, 2020.

- Biomimicry Institute videos.

- Johan Rockström, TEDGlobal 2010, July 2010, “Let the environment guide our development.”

- Johan Rockström, TED, Countdown, “10 years to transform the future of humanity - or destabilize the planet,” October 2020.

Selected articles:

Kate Raworth, “Meet the doughnut: the new economic model that could help end inequality,” World Economic Forum, April 28, 2017.

Daniel Boffey, “Amsterdam to embrace ‘doughnut’ model to mend post-coronavirus economy,” The Guardian, April 8, 2020.

Ciara Nugent, “Amsterdam Is Embracing a Radical New Economic Theory to Help Save the Environment. Could It Also Replace Capitalism?,” Time 2030, January 22, 2021.

Sam Meredith, “Amsterdam bet its post-Covid recovery on ‘doughnut’ economics - more cities are now following suit,” CNBC, March 25, 2021.

Kate Goodwin, “Designing the Doughnut: A Story of Five Cities,” matchbox.studio, April 19, 2021.

Indio Myles, “Carlota Sanz On Doughnut Economics and Becoming A Regenerative Global Society,” Impact Boom, October 22, 2021.

Kate Goodwin, “Who makes a Doughnut Economics community?,” matchbox.studio, November 29, 2021.

For my previous Sierra Atlantic articles on related topics, see:

· “Protecting Our Oceans - Educational Resources”

· “Key Resources on Recent Climate Change Reports”

· “Key Resources on Recent Climate Change Reports: Part II”

· “The Drawdown Project to Reverse Global Warming”

· “The Social Cost of Carbon & Why It Matters”

· “Ecological Footprints and One Planet Living”

· “Five Years of Activism: NYC Commits to Fossil Fuel Divestment”

· “State Must Pass Divestment Act Targeting NYS Common Retirement Fund”

· “Initiatives to Reduce Plastic Pollution”

· “Carbon Footprints and Life-cycle Assessments - Educational Resources”

· “Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature - Educational Resources”

· “The Circular Economy - Educational Resources (Part I)”

· “Earth Day 50 and the Coronavirus Pandemic - Educational Resources”

· “Educating for American Democracy”

· “High-rise Passive House in NYC”

· “Passive House Update -- Educational Resources”

· “NYC Enacts Legislation to Promote All-Electric Buildings”