It is a critical month for community groups and activists in Lamu County, Kenya who -- amidst intimidation and harassment -- are using the tools at their disposal to fight a proposed coal plant that threatens to destroy the main economic drivers of the region: tourism and fishing.

An island off the northern coast of Kenya, Lamu is known for its beaches and unique architecture; Lamu Old Town is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The 1,000 MW coal plant would be 15 miles north of the old town, and it is anticipated that environmental and social destruction from the coal plant would spread throughout the region, harming air, waterways, and communities. The economic risks of building a new coal plant in 2017 – when coal plants are being cancelled around the world – are high, and Kenya’s renewable energy potential is significant.

Earlier this week, the Kenyan government signed an agreement with Chinese company Power Global to finance the plant. This agreement was signed in the midst of an ongoing process to re-examine the environmental and social impacts of the plant, which activists from the local coalition Save Lamu say were not sufficiently assessed in the lead up to the licensing of the plant.

A coal plant does not make sense for Kenya given the tremendous renewable potential there, and especially should not be supported by public finance from the African Development Bank.

A chance to reconsider

This month, the National Environmental Tribunal (NET) of Kenya is holding two sets of hearings relating to the proposed plant, the second set of which will be next week: Monday, May 29th and Tuesday, May 30th. The first set of NET hearings were held earlier this month, and a detailed account is available here.

The NET is holding these hearings in response to complaints by Save Lamu. Save Lamu has argued that the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment was inadequate and thus the plant should not have received a license from the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA). In February 2017, Kenya’s Energy Regulatory Commission overruled previous environmental objections and claimed it was confident that environmental concerns would be adequately addressed.

The fact that the NET is now listening to Save Lamu’s perspective is a hopeful development. However, the fact that the financial agreement was signed before the NET reached its conclusion has cast doubt onto the impartiality of the tribunal.

For now, the best possible outcome to hope for from the NET hearings is the possibility of a delay to the start of construction. If construction is delayed beyond the elections, it is possible that a future government may oppose the coal project altogether. This possibility has led some coal plant proponents to try to speed up the process of building the plant.

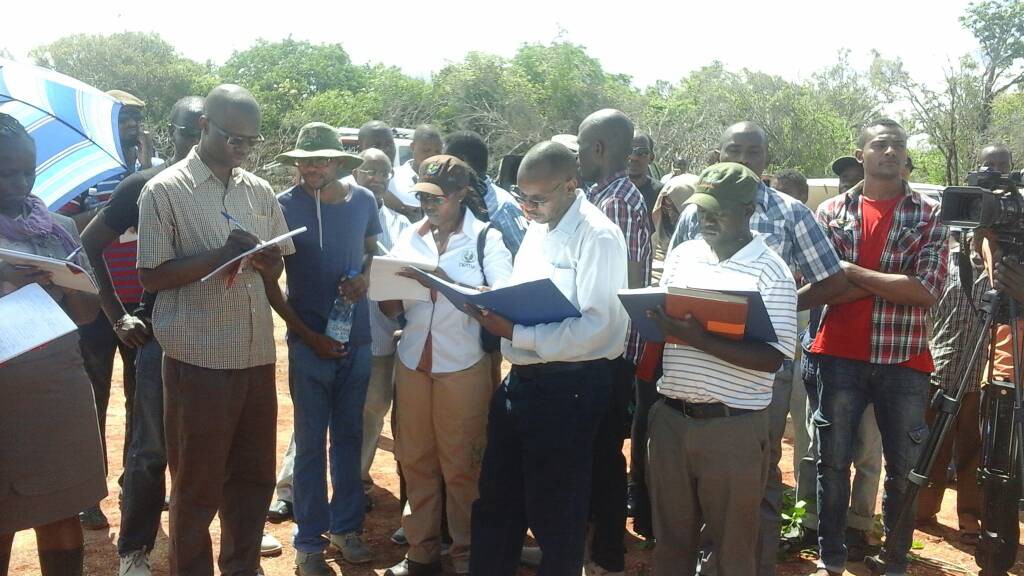

National Environmental Tribunal hearings in Lamu, Kenya (photo: deCOALonize)

The wrong place, the wrong time, the wrong approach

The proposed $2 billion plant would be the first coal-fired power plant in Kenya. The plant’s development is being led by Amu Power Company, with an investment consortium including East African Centum Investments and a number of Chinese companies. The plant would initially be supplied with coal from South Africa, but there are proposed plans to eventually supply it with coal mined in Kenya. This plan would require expanding mining in Kenya and would open a Pandora’s box of additional environmental impacts relating to coal mining and transportation.

The Lamu plant is part of Kenya’s plans to nearly double its electricity generating capacity to 6,700 MW by 2017. Proponents of this approach argue that more electricity is needed to power industry and provide energy access to unelectrified populations in Kenya. Among the industrial uses of the coal plant would be support for a massive proposed port and oil and gas pipeline.

While all these projects come with social and environmental risks, let’s focus for now on coal, which is the wrong approach to electricity generation in the 21st century anywhere in the world, but especially in Kenya.

In addition to abundant evidence that coal will not end energy poverty, coal is a failing industry. Worldwide, plans for proposed coal plants are being scrapped due to increasing recognition that coal is a lousy financial investment. Just this week, India cancelled almost 14 GW of proposed coal plants, due in part to the fact that plummeting solar costs make coal an increasingly uncompetitive option. In Kenya specifically, renewables are already responsible for nearly a third of electricity generation. There is high potential for further development, and a feed-in tariff and power purchase agreements make Kenya an appealing place for clean energy development. The viability of renewable options in Kenya underscore the absurdity of building a coal plant in Lamu.

The need to consider environmental and social impacts

International approaches to climate change, including the Paris Agreement, which Kenya has ratified, require countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Kenya’s commitment to this agreement included expanding geothermal, wind, and solar production. Coal, the single biggest contributor to climate change, undermines such endeavors. This results in social and environmental harm both locally and globally.

Local impacts to the environment and jobs would likely be severe. As evidenced by other coastal coal plants around the world, such as the Tata Mundra plant in India, water pollution from coal plants has devastating impacts on fishing communities. In Lamu County, fishermen support an estimated 75 percent of local households and community advocates fear the crushing impacts the coal plant would have on their livelihoods. While some argue that the coal plant would bring jobs, community groups have called these claims into question. The pristine environment that makes Lamu such a popular destination for also tourists also stands to be threatened by coal development.

To make matters worse, it appears that local communities that could be impacted by the project have not received full information about the project. As Accountability Counsel has pointed out, the public hearings about the project have been held in an inaccessible location. Additionally, the company has – perhaps unsurprisingly – emphasized possible project benefits while failing to adequately respond to concerns about risks and negative impacts. As Save Lamu has tried to hold community meetings to fill in the awareness gaps about the impacts of the project, they have been met with interference, intimidation, and harassment by public officials including the police. Both the partial information provided by the company and the efforts to thwart the work of Save Lamu have resulted in a deeply flawed public participation process.

Lamu residents protesting the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) decision to hold a public hearing in an inaccessible area last December (photo: Save Lamu)

The future of the Lamu coal plant

The future of the Lamu coal plant remains to be seen, but the devastating impact it would have on local tourism and fishing industries – and the communities who depend on them – hang in the balance. Given the failing economics of coal, a new coal plant is a bad investment, especially in a country with such a favorable environment for investment in renewables.

Because of the obvious threats to the public interest, both locally and globally, it is especially important that public institutions refrain from supporting this project. The African Development Bank is currently considering a partial risk guarantee for the plant. The African Development Bank, whose mission is to “spur sustainable economic development and social progress in its regional member countries” would be contributing to poverty and pollution by supporting this project with a partial risk guarantee. Additionally, it would be supporting a project whose public engagement process has been deeply problematic.

Support from the African Development Bank in Kenya should contribute to true inclusive and green growth, through renewable energy and infrastructure projects with transparent public engagement processes.