My Why

I was drawn to the advocacy and political space because I believe that communities and everyday people can help bring about real change. It’s inspiring to see coalitions unite to voice their concerns and empower regular people to better their communities.

My Role at the Sierra Club

My professional journey is an interesting mixed bag. I planned to enter the healthcare or research fields, but I volunteered for a presidential campaign as an undergraduate student. I instantly became hooked on organizing and continued to work on issue advocacy and electoral campaigns throughout my undergraduate and graduate careers. While working as a scientific researcher, I studied the post-Superstorm Sandy recovery efforts in New York City. While interviewing many homeowners impacted by the superstorm, I noticed that the words “climate change” didn’t resonate with everyone. Some folks would tell me it’s a “hoax,” but when I would describe climate change without saying those exact words, they agreed with the science and said they expected more frequent and intense storms in the future. At that moment, I realized I wanted to find an avenue to advocate for better environmental policies while conveying the issues more effectively to the general public. I was still working on electoral campaigns when I eventually found an opportunity to work for Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign as a digital campaigner. During my first year at the Sierra Club, I participated in the Victory Corps program and directly engaged with members who cared about electing good environmental champions. I was excited to transition to political work full-time when the PAC Director role opened.

Increasing Representation in the Movement

I recently attended a congressional candidate breakfast and noticed I was the only woman of color in the room. This situation is not new to me, but it’s a reminder that politics needs more diversity. I didn’t come from a background in politics or government, and pursuing a field that is brand new to you and people in your community is often scary. I’m the first AANHPI PAC Director at the Sierra Club, and I hope that in the future, more individuals from the AANHPI community will pursue leadership positions either at the Sierra Club or in the broader environmental movement. Polls and data show that the AANHPI community is concerned about the climate crisis, but many of us are not part of the conversation. Being the first can be intimidating and empowering – you feel the pressure of representing specific communities, but are also the voice for those who are usually forgotten. Diversity has increased since I entered politics more than 16 years ago, and we need to continue on this path. I take the time to mentor people of color starting in the field to ensure representation increases for generations to come.

What Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) Heritage Month Means To Me

AANHPI Heritage Month is a time to celebrate our unique communities and the diversity of the diaspora. While we share many commonalities in our stories, the AANHPI community is not a monolith. Over the years, I have learned to appreciate my South Asian heritage and how my cultural background has shaped my worldview and identity. This month is a time to reflect on the struggles of those before us and the hardships many have endured yet persevered through. As an immigrant myself, I never, in my wildest dreams, imagined that I would be working in the nation’s capital to help elect candidates at the federal level.

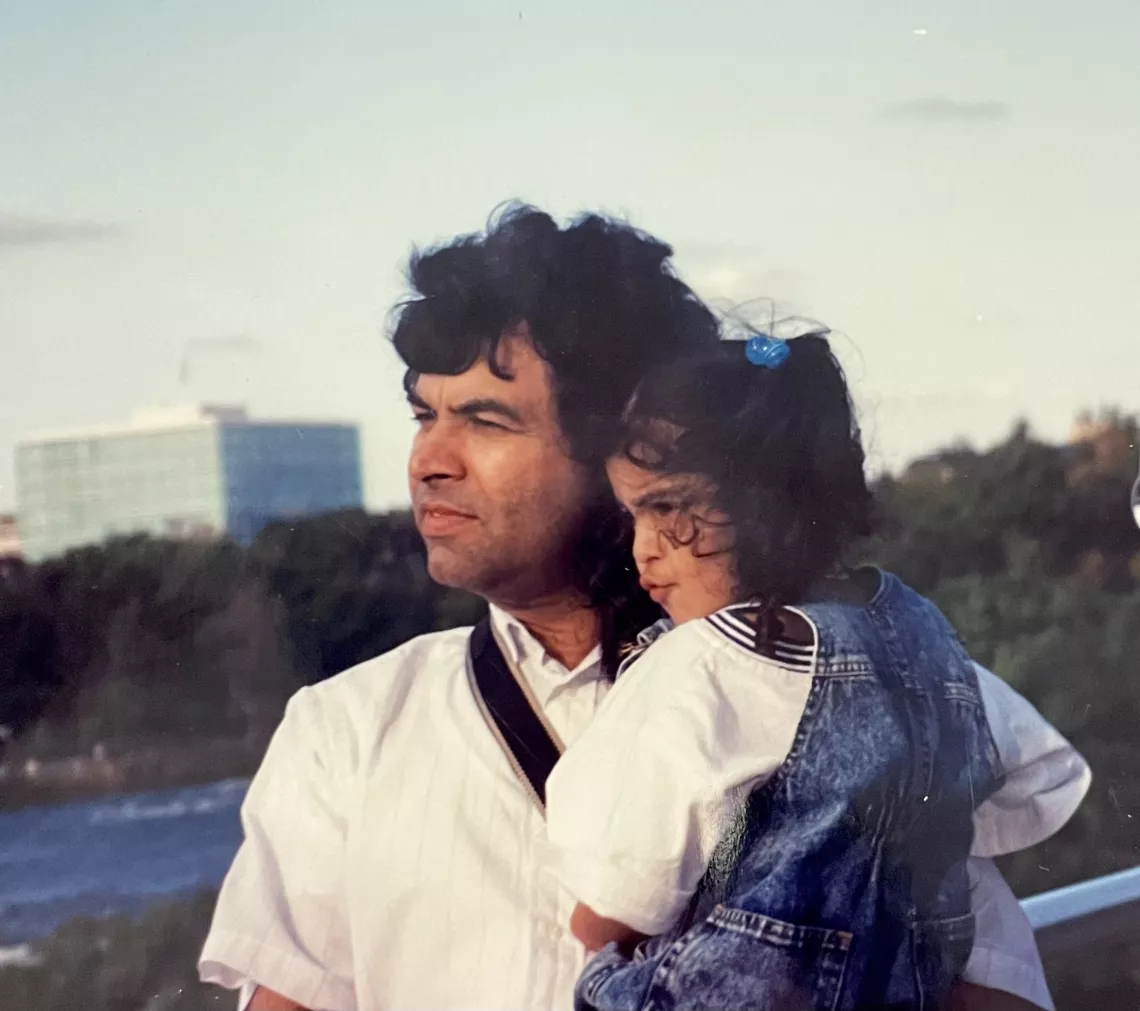

My father came to the United States with only eight dollars in his pocket and a dream of a better future. Although he faced tremendous challenges, his story is like many immigrants. It’s important to celebrate, tell our stories, and educate our communities and others about the diaspora and the obstacles that AANHPI communities face.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw an increase in hate crimes against AANHPI communities. Unfortunately, hate crimes against these communities are nothing new. After 9/11, I remember people often shouted derogatory slurs at my family. The fear and hate that I experienced as a middle schooler post-9/11 was eerily similar to the uneasiness I felt while there was a rise in hate crimes during the pandemic. Many folks from the diaspora felt afraid and alone. A few of us in my community came together and organized a vigil to remember those who were lost locally and nationally from hate crimes. It was inspiring to see many members of the AANHPI community united, share a space to grieve, and know that there were neighbors, friends, and others who would also fight against AANHPI hate. The AANHPI community is often taught to be resilient and powerful through any struggles. Still, we must allow ourselves to be heard, especially when targeted and discriminated against.

Recently, I helped co-organize a Holi event in my community. Holi is a festival celebrated in India and called the “Festival of Colors” to celebrate the arrival of Spring. This was the first time a community-wide Holi event in my area was free and open to the public. I was surprised to see members outside the South Asian community so excited to participate and learn about a new holiday. People tried Indian samosas and mango lassi, threw colored powders, and danced. It reminded me how far America and I have come to fully embrace different cultures publicly. I was immensely proud that we were able to bring that sense of normalcy and belonging to younger South Asian children in the community.

When I worked as a Senior Census Advisor in 2020, there were many hurdles to getting an accurate count due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the constant changes implemented by the federal administration. Historically, underrepresented and marginalized communities were hard to reach due to mistrust of the government and, quite frankly, fear – whether they were citizens, immigrants, or undocumented. An accurate Census count brings resources into communities, and there is a misconception that the AANHPI diaspora generally has substantial financial means. This was another scenario where I served as an appropriate messenger to those communities because I was able to build trust over our shared experiences. My team developed resources in various languages to reach those communities, educate them about the need for an accurate count, and ensure their voices were heard.

Growing up, I was often seen as “other.” Even today, some people assume I am “foreign” and not from the United States When I was in elementary school, I remember taking a standardized test and filling out my ethnicity as “Asian." My teacher told me I identified myself incorrectly, even though I have Indian heritage and the subcontinent is part of Asia. At times, I even tried to mask my South Asian identity to blend in with my peers. It is encouraging to see how far we have progressed as more people accept the diaspora’s cultures, but there is still a lot of work to be done.