Last month, the New York Public Service Commission breathed new life into its long-dormant gas planning docket (20-G-0131) while also kicking off a new proceeding to assess implementation and compliance with the requirements of New York’s landmark climate legislation (22-M-149). These dockets have the potential to significantly shape the future of the gas system in New York and Sierra Club applauds the Commission for recognizing the need for New York’s gas distributions companies to start shouldering their share of the burden of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the state.

Unfortunately, while they have a number of positive features, the Commission’s recent orders leave the utilities’ hands firmly on the gas spigot, and if their recent actions and proposals are any indication, they will ensure that as much gas as possible flows through that spigot. If New York is going to avoid replicating the mistakes of Northeast neighbors like Massachusetts—which to date has allowed utilities to impose their will on its own gas planning process—significant additional procedural safeguards will be required.

Part I of this blog explores the climate challenge buildings present and how, absent utility opposition, highly efficient electric heat pumps are poised to significantly address this challenge.

New York’s buildings have a gas problem

Like many other states, New York stands at a crossroads in gas utility planning. New York’s signature Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, passed in 2019, requires an 85 percent reduction in the State’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 2050. Currently, buildings are the largest source of GHGs in New York, accounting for 32 percent of statewide emissions. Simple math reveals that New York cannot reach its climate mandates without substantial emission reductions from the building sector. Yet, to date, comparatively little has been done to address the climate impacts from buildings.

Building emissions come primarily from the equipment we use to heat and cool our homes (like gas furnaces or oil burners) as well as from hot water heaters and stoves. In New York, 73 percent of residential buildings are heated with gas, which is delivered through the interstate pipeline system and local distribution system to people’s homes. Between 2005 and 2014, New York added more than 500,000 households to its gas system, more than the rest of the country combined (326,000).

While gas burns somewhat more cleanly than heating oil, the extraction and transport of gas from fracking wells in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia results in significant leakage of methane gas, a potent greenhouse gas. By some accounts, when full lifecycle emissions are considered, heating with gas results in more emissions than heating with oil.

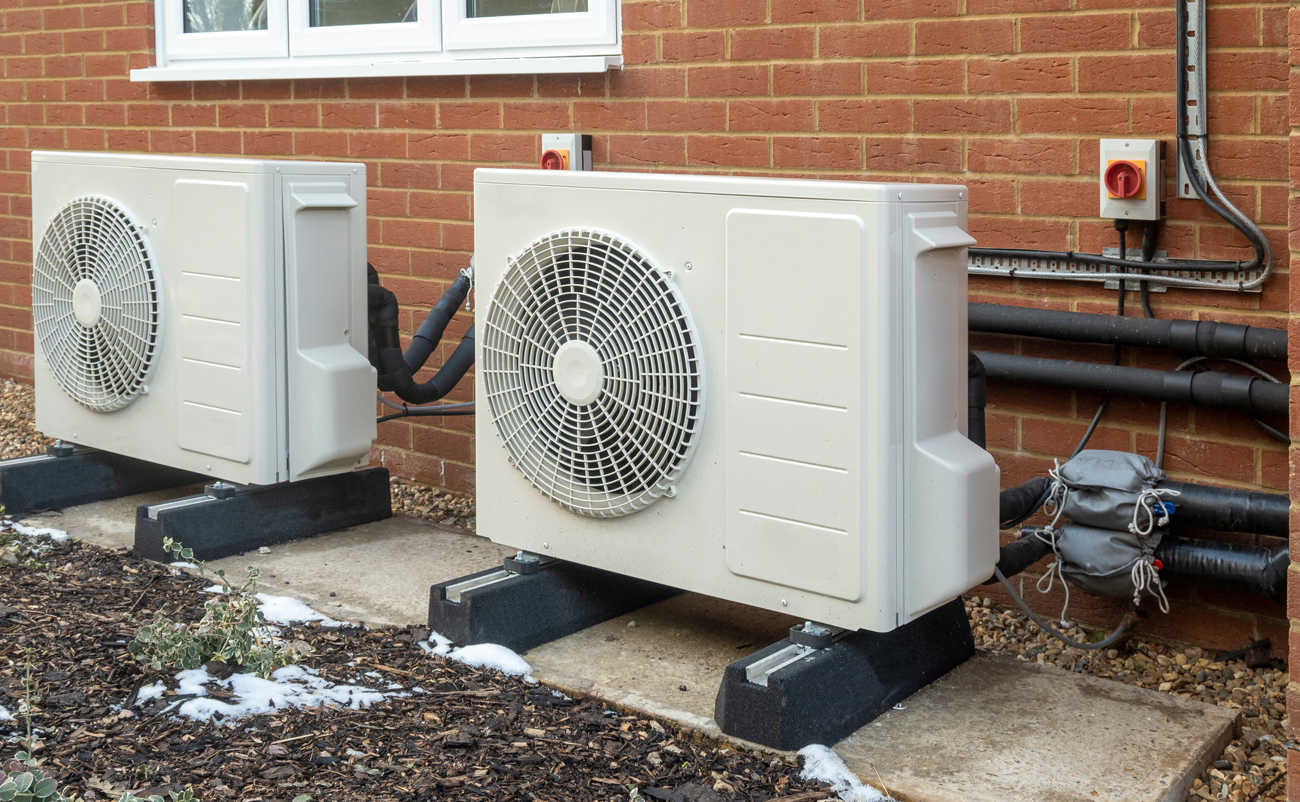

An alternative to gas that is widely used in many parts of the country is electric heat pumps. Rather than combusting a fuel, as occurs in a gas furnace or oil burner, heat pumps work by extracting heat from the ambient air and transferring it from outdoors to indoors. Heat pumps are remarkably efficient. They also function in a wide range of climates. Heat pumps generate no direct emissions. Moreover, since they are powered by electricity, and New York’s climate law mandates the State achieve 100 percent zero-emissions electricity by 2040, so electric heat pumps enable the complete elimination of emissions from building heating and cooling.

Electric heat pumps sound great! What’s the problem?

Electric heat pumps’ primary—and perhaps only—shortcoming is not technological, but rather political. Gas-only utilities lose money if their customers switch from gas to electricity for their home heating needs, and combined gas-electric utilities make more money from continued investment in their gas distribution systems than from serving the new heat pump load on the electric side.

To understand utilities’ resistance to electric heat pumps, it is critical to understand how utility shareholders make a profit. As regulated monopolies, utilities are allowed to recover their costs of doing business (i.e., providing gas or electricity to their customers) through the rates they charge their customers for their product. While utilities get to recover all of their prudently incurred costs, they are allowed to earn a regulated rate of return—typically around 10 percent—on a subset of these costs. Specifically, capital investments are the holy grail for utilities. For gas distribution utilities, this means investments in their extensive system of pipes and services that connect their customers to the interstate gas pipeline system. All investments they make in maintaining or expanding their gas systems are repaid by their customers together with their guaranteed rate of return. Sound like a money-making formula? It is! Even in this year of unstable markets, utility shares have rallied.

In recent years, utilities have been able to reap enormous profits by systematically investing in replacing their thousands of miles of older steel and cast iron pipes. This strategy of replacing so-called “leak-prone” pipes was initially justified as a safety measure, but is increasingly being rebranded as a climate solution. Methane leaking from the gas distribution system is indeed a climate problem. But given our ability to detect and prioritize for repair the more substantial leaks in the system in a targeted manner, the practice of engaging in wholesale pipe replacement warrants some scrutiny.

Let’s consider the price tag. New York utilities in their recent rate cases have estimated the cost of replacing leak-prone pipe at $250-$1,650 per foot or $1.3-$8.7 million per mile. According to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, there are nearly 22,300 miles of steel and cast iron pipe in New York State. Replacing just the uncoated steel and cast iron pipes—the categories typically deemed “leak prone”—owned by the National Grid gas utilities (KEDNY, KEDLI, and Niagara Mohawk) and Consolidated Edison alone would cost $26 billion! Shareholders of those utilities are undoubtedly salivating over the 10 percent—or $2.64 billion—that they could earn by completing this transition.

Electric heat pumps pose a threat to this cash machine for utility shareholders. If, instead of replacing all of the bare steel and cast iron pipes, customers switched to efficient electric heat pumps and utilities systematically shut down portions of the gas system, these massive capital expenditures would no longer be necessary and utilities couldn’t justify recovering the costs. In Part II of this blog, we’ll explore utilities’ alternate vision for the future of gas.