In January, we received a trove of email documents through a public records request that revealed that Rebeckah Adcock -- a former pesticide lobbyist -- continued emailing and aiding her pesticide industry contacts while working as senior advisor to the Secretary of Agriculture, focusing on regulatory policy.

In one email exchange about a meeting between Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue and Dow AgroSciences's then-CEO, a lobbyist made light of Adcock's conflicts of interest: "Maybe you can have a chair on both sides of the table." Adcock responded, in part, "If I am in room, happy to help both!"

It was just one more example of how the USDA and its political appointees have been using public resources to advance the private gains of megacorporations during the Trump era. Yet we knew there was more to this story, buried in the thousand pages of documents.

Hundreds of supporters helped sort through the mountains of emails to unearth more examples of corporate acquiescence and ethical impropriety. Here's just some of what was discovered:

Cozy emails with former industry contacts

Adcock exchanged affectionate emails with a number of industry contacts, including former colleagues at the Kentucky and American Farm Bureau Federations.

While there wasn't much correspondence with her most recent employer -- the pesticide industry trade group, CropLife America -- Adcock talked to big players who were members of CropLife America around that time: Bayer, Dow AgroSciences, DuPont, FMC Corporation, Monsanto, and Syngenta. (Several of these corporations have since merged.)

Adcock also traded emails with people who represented CropLife America through its lobbying firm, though the matters discussed were related to other clients. The "both sides of the table" comment was from one of these contract lobbyists; another traded jokes about biotech issues like genetic engineering.

Embedded throughout these emails was a consistent theme: Adcock was there to assist agribusiness; public health and environmental concerns rarely came up.

The Farm Bureau's one-sided relationship with Adcock

Farm Bureau senior lobbyist Don Parrish received a level of deference not offered to any other external stakeholder. Parrish would send short emails asking Adcock to call his cell phone with no context, and Adcock would quickly oblige.

One time, Parrish simply emailed "got a minute?" in the subject line, with no other information. Adcock responded a minute later saying that she was busy but "may try over lunch."

Other times, Parrish skipped the questions and got straight to the point. "Have a great weekend … but need to visit next week." Adcock's one-word reply: "OK."

In another email with the subject line, "when you get a minute," Parrish said, "Let's visit. thanks." Adcock promptly replied: "10-4."

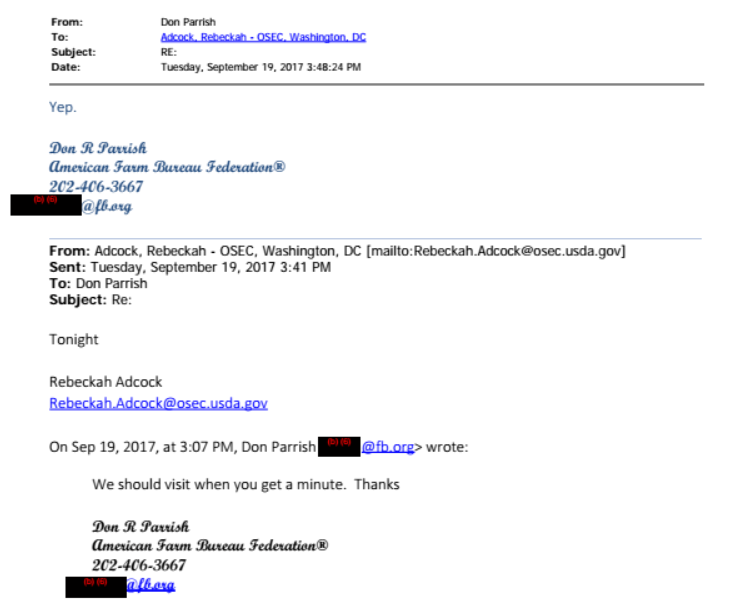

In yet another email with no subject line, Parrish wrote, "We should visit when you get a minute. Thanks." "Tonight," Adcock replied. "Yep," Parrish confirmed.

While it's impossible to know precisely what they talked about most of the time (which may have been the point), other emails clearly evidenced the Farm Bureau's desire for exemptions from the Clean Water Act for certain land uses. Parrish related the case of an Illinois farmer who was investigated for improperly filling a tributary, and enlisted Adcock to assist them in dealing with the Army Corps of Engineers and Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Rolling back clean water protections has become something of a hallmark of the Trump administration. Right now, the majority of waterways in the continental US are at risk after the EPA limited what types of wetlands and waterways are safeguarded by the Clean Water Act.

Off-the-record presentations to industry groups

Adcock spoke with Monsanto's Vegetable Advisory Council in "an informal, off-the-record conversation" about the direction of policy and regulation at the Department of Agriculture -- efforts that Adcock was overseeing as the agency's regulatory reform officer.

Vegetable industry leaders were especially keen on discussing food safety, pesticides, organic standards, and "access to labor" (which often refers to immigration rules and pay standards).

When discussing the makeup of the advisory council, Monsanto's director of government affairs noted that Adcock "will undoubtedly recognize or know some of the organizations and individual members."

Adcock also traveled to the Farm Bureau offices to talk with the Ag Biotech Alliance about upcoming changes to GMO labeling and regulations. Months after the meeting, the USDA reconsidered its oversight plan for potential invasive GMO plant pests; it eventually decided to allow companies to "self-determine" not only whether they needed USDA approval, but whether they even needed to notify the agency at all. The final GMO label rebranded GMO products as "bioengineered" and created loopholes big enough to squeeze a whole grocery store through.

She also spoke to members of the Minor Crop Farmer Alliance on a call. The organization, which seeks to "ensure the continued availability of crop protection chemicals for minor use crops," was eager to discuss how the Department of Agriculture's new leadership could help shift the Environmental Protection Agency to a more accommodating approach on pesticide regulation, trade, and endangered species and pollinator protections.

That may not have been necessary -- even by this early point in the Trump administration, both the USDA and EPA had already become much more deferential to industry interests and desires.

Insensitive language used to describe workload

The life of an administration official is certainly busy, though Adcock may have crossed the line of good taste by referring to her schedule as "a death march," "like prison," and, depending on what she was referring to, "voluntary water boarding."

Quick help for groups seeking regulatory relief

The National Council of Farmer Cooperatives reached out to Adcock to see if she could get her department's assistance in blocking a federal policy. The DC Circuit Court had ruled that the EPA could not exempt farmers from reporting high amounts of air pollution generated by animal waste.

The council was exploring ways to avoid this reporting, and Adcock was sympathetic, promising to check around within the department. "Can't believe the courts made this absurd decision without any thought whatsoever as to how it might actually occur … then again yes I can."

Ultimately, Big Ag got Congress to change the law. The EPA later used this as justification to exempt animal waste at farms from a separate community right-to-know law.

A few months later, the Defense Logistics Agency sent food manufacturers a letter about certain prohibited ingredients in troop meals, including trans fats, partially hydrogenated oils, and soy protein extenders. The move was "to promote healthier eating for optimum warfighter performance," but manufacturers raised objections.

The National Council of Farmer Cooperatives lobbyist reached out again to Adcock, noting that even though the letter had been rescinded, "groups are pursuing options via appropriations should they become necessary," likely using the congressional funding process to prevent these food ingredients from being prohibited in the future. Adcock responded, "Good Grief. Let me do some digging here." She then connected another staff member with the lobbyist to discuss the council's concerns "and how USDA might be a constructive voice."

The bigger picture: A lobbyist takeover

Adcock has since become the Administrator of the Rural Business-Cooperative Service, another influential position, but she's far from the only ex-lobbyist in the Trump administration to have that level of clout.

Another senior advisor to the secretary, Kristi Boswell, also formerly lobbied for the Farm Bureau. Senior Advisor Brian Klippenstein, who has since left the agency, was previously the executive director for an anti-animal-welfare group called Protect the Harvest. Kailee Tkacz worked for snack food manufacturers, corn refiners (who produce high fructose corn syrup), and grocery stores before becoming a policy advisor for food and nutrition and, eventually, chief of staff for the deputy secretary.

Other higher-ups at the USDA included former lobbyists for trade groups of pork producers, beef ranchers, wheat growers, corn growers, and various state-level Farm Bureaus. Even Secretary Perdue has been criticized for intertwining his political career with his business interests.

Experts have a term for this lobbyist takeover: "regulatory capture." It describes how government agencies can be infiltrated or co-opted to serve the commercial interests of industry groups. And it's not just the Department of Agriculture -- under Donald Trump, virtually every agency has seen an explosion of political appointees who have obvious conflicts of interest embedded in their resumes. Disgraced former EPA administrator Scott Pruitt and Interior secretary Ryan Zinke were each forced to resign after the Sierra Club revealed appalling examples of corruption found through public record searches.

But government transparency takes time, and we are especially grateful that hundreds of supporters sifted through almost 1,000 pages of material to discover these examples. Rest assured that we will continue to monitor what our public officials are up to, whom they're talking to, and why it matters to you.

Array