The Sierra Club has carefully tracked modern mining developments in Wisconsin beginning with the Flambeau mine. We do so because mining operations are among the most polluting and destructive industries on the planet producing far more wastes than marketable by-products – wastes that must be managed safely forever. Thanks to friendly tax codes and development incentives, mining companies also have far more resources than local residents and regulatory agencies with which to promote their proposals. This puts public interests and Wisconsin’s environment at a huge disadvantage when a mining company comes to town.

The Sierra Club has carefully tracked modern mining developments in Wisconsin beginning with the Flambeau mine. We do so because mining operations are among the most polluting and destructive industries on the planet producing far more wastes than marketable by-products – wastes that must be managed safely forever. Thanks to friendly tax codes and development incentives, mining companies also have far more resources than local residents and regulatory agencies with which to promote their proposals. This puts public interests and Wisconsin’s environment at a huge disadvantage when a mining company comes to town.

Under Governor Walker’s administration, the GOP-controlled legislature passed additional enabling legislation that gutted environmental protections such as Bad River Watershed Destruction Act (2013 Act 1) and repeal of the Prove It First law (2017 Act 134). The John Muir Chapter is committed to repealing both of these damaging laws.

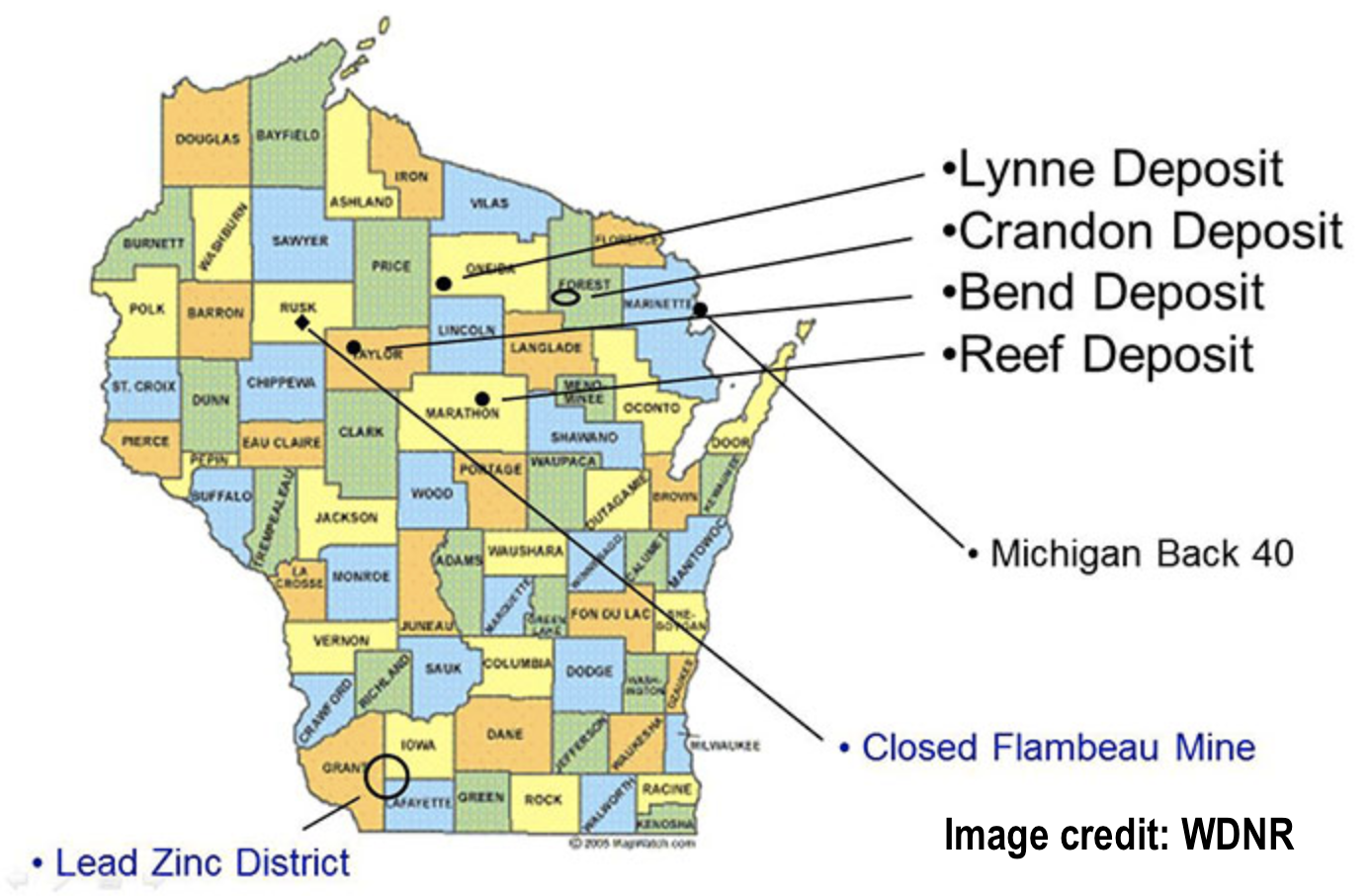

On these pages we chronicle some of the success stories of work that the John Muir Chapter has done to fight deregulation that favors this highly polluting industry whether for taconite or metallic sulfide ores and to fight against specific proposals threatening Wisconsin’s precious ground and surface waters, wetlands and air, wildlife habitat and public health. We’re proud of the work our volunteers and staff have done to work collaboratively and cooperatively with many state conservation, environmental, Native Nations, and other groups on these complicated and destructive proposals. Some known deposits in sensitive places do not yet have permanent protections and the John Muir Chapter will remain vigilant for future mining development proposals and ready to engage Sierra Club members and the public.

Lynne deposit in Oneida County

The Lynne deposit is one of only a handful of potentially “economic” metallic sulfide deposits identified in Wisconsin to date. It was discovered by now defunct Canadian mining company, Noranda in 1990 and an initial proposal to mine there was submitted in 1992. The deposit lies on Oneida County Forest land within one half mile of the protected Willow River and the County controls both surface and mineral rights. Noranda abandoned the proposal in 1993 after it was shown the deposit lies beneath pristine wetlands and lakebeds that would make mining there much more difficult or even prohibited due to the Public Trust Doctrine that protects navigable waters such as lakes.

Lynne is a relatively small deposit of approximately 5 million tons that was projected to yield around 640,000 tons of ore to be processed for zinc, lead, gold, silver, and copper (listed in order of value from highest to lowest). As with all metallic sulfide deposits, the vast bulk of the mined material becomes waste rock or waste tailings that requires virtually perpetual treatment and monitoring (learn more about metallic sulfide mines here). By contrast the Flambeau mine produced 1.9 million tons of ore along with 8.5 million tons of waste rock. Despite its small size, the mining industry has continued to pursue exploration of Lynne including a 2009 proposal by Canadian exploration company Tamerlane Ventures that was voted down by the Oneida County Board of Supervisors.

Lynne is a relatively small deposit of approximately 5 million tons that was projected to yield around 640,000 tons of ore to be processed for zinc, lead, gold, silver, and copper (listed in order of value from highest to lowest). As with all metallic sulfide deposits, the vast bulk of the mined material becomes waste rock or waste tailings that requires virtually perpetual treatment and monitoring (learn more about metallic sulfide mines here). By contrast the Flambeau mine produced 1.9 million tons of ore along with 8.5 million tons of waste rock. Despite its small size, the mining industry has continued to pursue exploration of Lynne including a 2009 proposal by Canadian exploration company Tamerlane Ventures that was voted down by the Oneida County Board of Supervisors.

Oneida County chose to rewrite its formerly protective mining ordinance after 2017 Act 134 was passed that eroded state protections and under pressure by mining proponents including Senator Tom Tiffany to limit their ordinance. Sen. Tiffany and other proponents argued that local governments such as Oneida could not have local controls on mining that were more protective than state law and threatened that the legislature might pass further limits on local control.

The John Muir Chapter worked with local Oneida County residents, the Protect The Willow group and the River Alliance of Wisconsin to oppose the rewritten ordinance on the grounds that local governments can enact limited protections that are greater than state law. Despite this effort, the Oneida County Board approved the new ordinance that limited their ability to enact additional protections.

At the same time, the Oneida County Board authorized a non-binding referendum for the 2018 fall election asking voters whether the County should open Forest Land up for exploration and mining. The John Muir Chapter again worked with Protect The Willow, the River Alliance and local residents to educate our members and the public on the dangers of developing the Lynne deposit. The result was an overwhelming vote against the referendum with 62% of County voters saying no and the County Board Chairman stating that mining at Lynne was “off the table.”

The victory in Oneida County resulted in a resounding no to both local elected officials that have been mining proponents and to the mining industry itself. Until there are permanent protections in place, the John Muir Chapter will continue to monitor the Lynne site for any new proposals or developments.

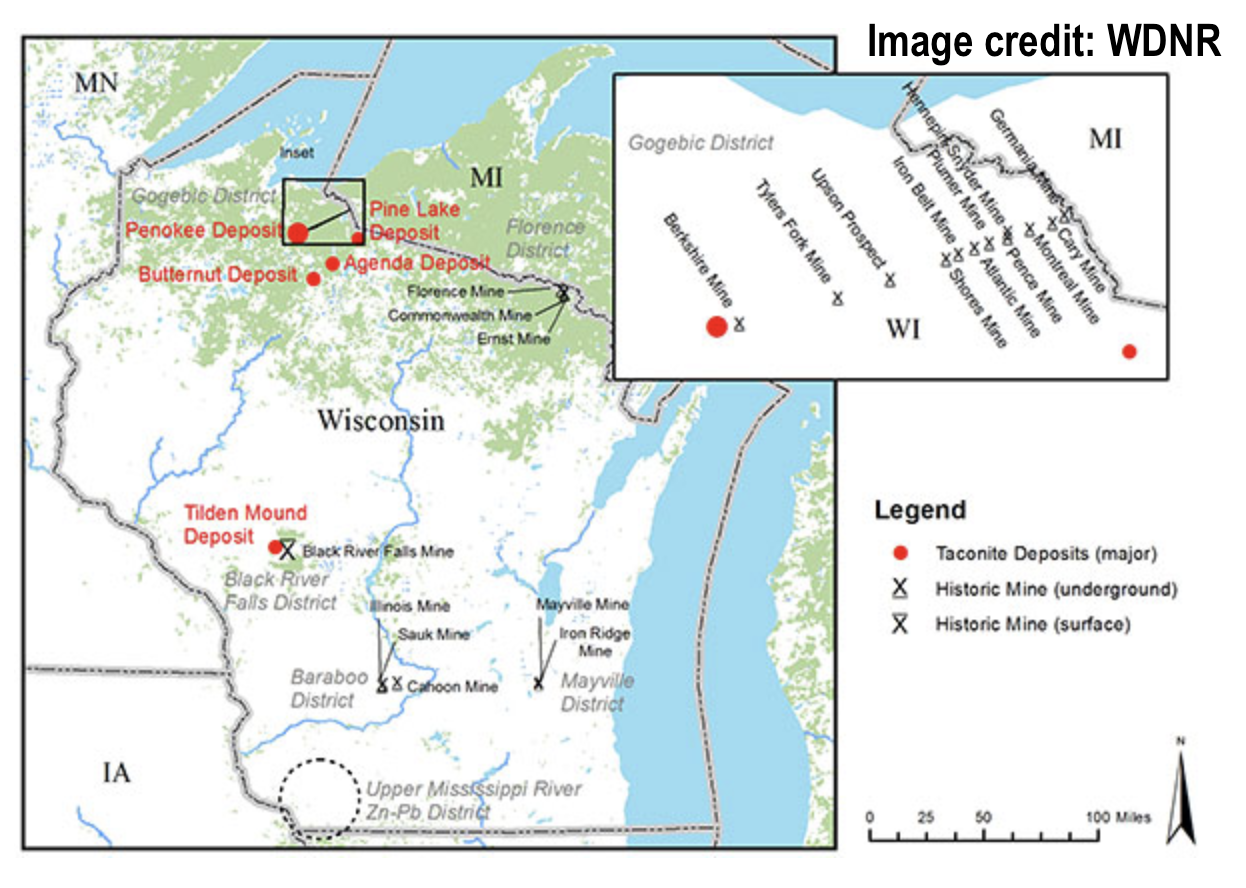

Gogebic Taconite in the Penokee Hills

Shortly after Scott Walker’s election to Governor in 2010, draft legislation to deregulate ferrous or iron mining (specifically low-grade iron ore known as taconite) was introduced. At the same time, Gogebic Taconite - a new mining company with only coal mining experience - was formed and granted a Wisconsin exploration license in early 2011. Gogebic Taconite’s (“GTac”) target was the known low-grade iron deposits along and in 22 miles of the scenic and largely undeveloped Penokee Hills range of Iron and Ashland Counties of northern Wisconsin.

The taconite ore is found in the headwaters of the Bad River Watershed of Lake Superior. The Penokee ridge feeds water in all directions to the Bad River and the open pit would be in the center of the ridge. It is an extremely water-rich environment with thousands of acres of pristine wetlands. The Bad River flows through Copper Falls State Park and into the Kakagon and Bad River Sloughs of Lake Superior. If developed, mining would threaten the sacred wild rice beds of the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe and their way of life. The Kakagon and Bad River Sloughs of the Bad River and Lake Superior together are a Ramsar Wetland of International

The taconite ore is found in the headwaters of the Bad River Watershed of Lake Superior. The Penokee ridge feeds water in all directions to the Bad River and the open pit would be in the center of the ridge. It is an extremely water-rich environment with thousands of acres of pristine wetlands. The Bad River flows through Copper Falls State Park and into the Kakagon and Bad River Sloughs of Lake Superior. If developed, mining would threaten the sacred wild rice beds of the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe and their way of life. The Kakagon and Bad River Sloughs of the Bad River and Lake Superior together are a Ramsar Wetland of International

Importance and the Kakagon Sloughs are a designated National Natural Landmark due to the uniqueness of the sloughs and the size of the natural wild rice beds. At 16,000 acres, they are the largest and healthiest full-functioning estuarine system remaining in the upper Great Lakes region and have been called the Everglades of the North.

The state recognized the value of the Penokees when it identified it as an Important Bird Area and a Conservation Opportunity Area of Continental Significance in the 2005 State Wildlife Action Plan. The Action Plan identifies important conservation areas where Species of Greatest Conservation Need exist and identifies the Penokees as needing conservation to maintain them as a large, continuous, climate change-resistant forest. The state of Wisconsin also identified the Penokee Range as an important area to protect for its unique geology and future conservation and recreational opportunities.

While GTac conducted exploration drilling beginning in 2011, the company drafted legislation to deregulate iron mining via creating a separate and far less protective law. Until the passage of the Bad River Watershed Destruction Act (2013 Act 1) iron mining had been considered just as destructive as metallic sulfide mining and was regulated as such. GTac’s central premise and most important claim used to justify creation of a streamlined, less protective regulatory program for iron mining was that the iron ore in Ashland and Iron Counties is more environmentally safe compared to other ores. GTac and mining proponents claimed that the taconite ore there did not contain sulfide minerals (mainly pyrite) which can cause significant environmental damage to water supplies.

GTac and proponents lied to legislators and the public about the characteristics of the ore and waste rock that would be exposed by mining the Penokees. Independent reports such as that from Lawrence University on the geochemical characterization of the waste rock and the ore itself demonstrated that significant amounts of pyrite and other sulfide minerals are present. The confirmed presence of pyrite and sulfide minerals is extremely important as the mineral releases sulfates when exposed to air and water that form sulfuric acid which causes acid mine drainage of dissolved toxic metals.

GTac and proponents lied to legislators and the public about the characteristics of the ore and waste rock that would be exposed by mining the Penokees. Independent reports such as that from Lawrence University on the geochemical characterization of the waste rock and the ore itself demonstrated that significant amounts of pyrite and other sulfide minerals are present. The confirmed presence of pyrite and sulfide minerals is extremely important as the mineral releases sulfates when exposed to air and water that form sulfuric acid which causes acid mine drainage of dissolved toxic metals.

The presence of significant amounts of sulfide minerals in the ore and waste rock is more than just a management issue for a mining company. The basis for the whole bill and the reduced environmental protections written into it is simply incorrect and scientifically unfounded. The result was the creation of a streamlined and less protective program that is inadequate to deal with mining wastes expected to cause significant acid mine drainage.

GTac’s unsafe and risky proposal and the public outcry over its manipulation of Wisconsin’s legislative process via writing its own legislation was only one factor in the demise of the proposal. The open pit for the first phase of the proposal was estimated to become the largest open pit taconite mine in the world at 4.5 miles long by 1.5 miles wide. The first phase was estimated to produce an approximately 910 million tons of mining wastes such as tailings and waste rock that would have resulted in permanent destruction to sensitive lands and wildlife habitat, wetlands, streams destroyed and groundwater pollution despite so-called reclamation requirements.

Virtually all U.S. taconite production comes from the mines and processing plants in Minnesota and Michigan. The Sierra Club researched the recent environmental track record of these mines and found that every one of those operations has been fined for environmental violations from 2004-11. Those operations were responsible for massive pollution resulting in fines, cleanup orders and stipulations totaling over $10.5 million in that time period. The report also found that taconite processing plants are major sources of air contaminants including mercury, acid rain and greenhouse gases. Permitting the mine and processing plant in Ashland County would introduce a new major source of mercury to our already damaged lakes, rivers and streams.

Virtually all U.S. taconite production comes from the mines and processing plants in Minnesota and Michigan. The Sierra Club researched the recent environmental track record of these mines and found that every one of those operations has been fined for environmental violations from 2004-11. Those operations were responsible for massive pollution resulting in fines, cleanup orders and stipulations totaling over $10.5 million in that time period. The report also found that taconite processing plants are major sources of air contaminants including mercury, acid rain and greenhouse gases. Permitting the mine and processing plant in Ashland County would introduce a new major source of mercury to our already damaged lakes, rivers and streams.

Exploration of the also showed the presence of a highly dangerous asbestiform mineral called grunerite which raised even more concerns about the safety of the proposal, workers, and those downwind including residents, visitors and wildlife.

GTac’s exploration drilling and application for “bulk sampling” by the company created controversy and stirred strong public protests in 2013. In response to a single unfortunate incident with a protester in July, GTac deployed heavily armed paramilitary security at the mine site. GTac’s unhinged and provocative response was far in excess to any threat from unarmed protesters. Photos and media reports of the militia from Bulletproof Security of Scottsdale, Arizona carrying semi-automatic weapons were published widely and drew national attention. The security company was not licensed to operate in Wisconsin and was swiftly withdrawn from the site.

GTac worked with the legislature to quickly pass 2013 Act 81 – a new law that carved out a special exemption for GTac to withdraw the land it was leasing from the state Managed Forest Law (MFL) program. This exemption allowed GTac to close the land to the public – a legal right every state citizen has for land enrolled in the MFL – and effectively bar any protests from taking place on the site.

All of these factors – along with opposition organizing by dozens of state environmental and conservation organizations like the John Muir Chapter and especially by state tribes including the Bad River Ojibwe – were critical to pushing GTac out of the state in 2015. Public opposition to GTac’s enabling legislation including 2013 Act 1 and Act 81 was overwhelming and still ignored by the legislature. GTac withdrew and abandoned the proposal in 2015 and blamed the decision on having discovered far more wetlands at the site than was expected.

All of these factors – along with opposition organizing by dozens of state environmental and conservation organizations like the John Muir Chapter and especially by state tribes including the Bad River Ojibwe – were critical to pushing GTac out of the state in 2015. Public opposition to GTac’s enabling legislation including 2013 Act 1 and Act 81 was overwhelming and still ignored by the legislature. GTac withdrew and abandoned the proposal in 2015 and blamed the decision on having discovered far more wetlands at the site than was expected.

While GTac is gone, the landowners for much of the Penokees have restarted efforts to work with local governments to smooth the way for a new proposal to mine there. Iron County has had discussions with the owners while Ashland County has shown no interest in discussions to date. The John Muir Chapter remains committed to opposing mining in the Penokees due to the risks to such an amazing and sensitive part of our state along with the track record of the taconite mining industry and because there are no permanent protections in place.