Why Are People Finally Believing in Climate Change?

A climate communication expert talks bad weather, and young Republicans

Photo by RawPixel | iStock

A record number of Americans—73 percent—now understand that global warming is happening. About 62 percent of them know that humans are mostly responsible. What is bringing this change in understanding? Is it a generational shift? Or just a whole lot of bad weather?

Anthony Leiserowitz is director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC), which is behind this new data. Along with colleagues from George Mason University, the YPCCC has spent the last decade studying American awareness of climate change and how to shift that awareness. Leiserowitz spoke to Sierra about young Republicans, the weather report, and why it’s easier to explain climate change to a person in India than to a person in the US.

Sierra: The most recent survey that YPCCC has done shows awareness of climate change is at its highest since you started collecting data. What is it about right now that is significant?

Anthony Leiserowitz: The number of Americans who think global warming is happening is at an all-time high. We saw an eight percentage point jump in Americans who were very worried about climate change. That's a big surge. When you do these kinds of surveys twice a year, you're used to seeing changes that are one, two, or maybe three percentage points. Very rarely do you see that kind of movement.

Questions like “When will climate change start to harm people in the United States?,” “When will it harm you, your family, your community?”—we saw a big jump in those numbers— much more than “How much will it harm future generations or other plant and animal species?,” which are more distant.

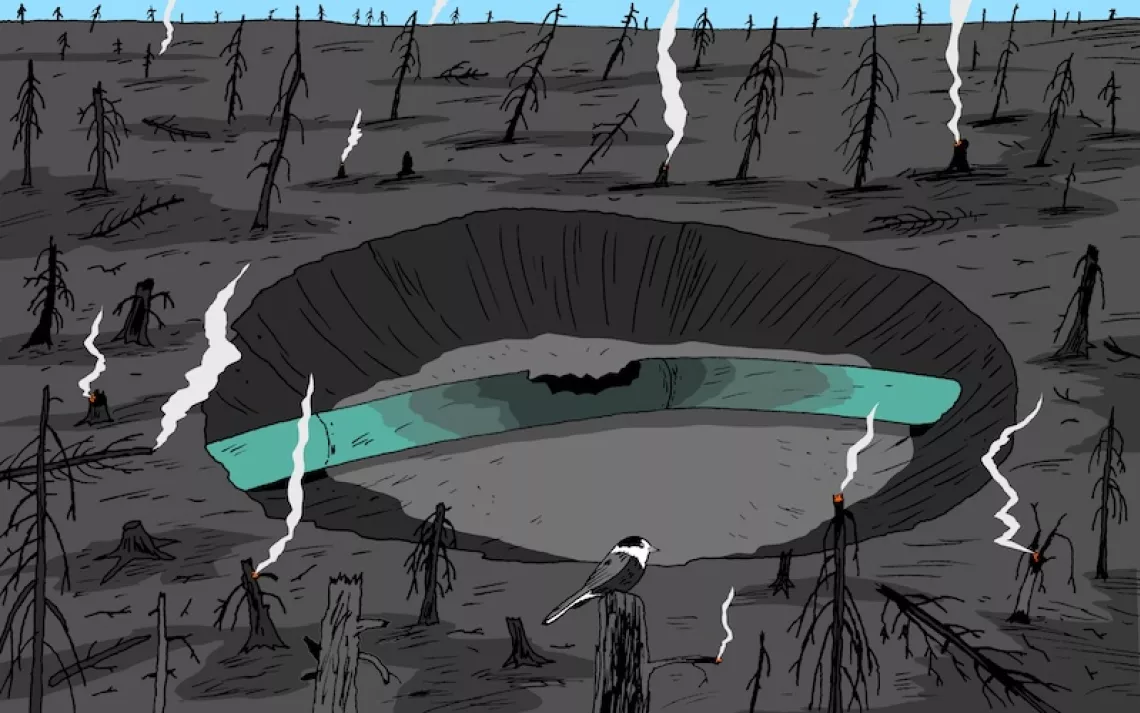

We think that in the end, this big jump from March to December 2018 has a few different things that have sort of converged. One is the extreme, record-setting weather—from Hurricane Michael destroying part of the Panhandle in Florida to the terrible wildfires that went on and on in California.

They still have a long way to go, but the media is beginning to use the words “climate change” when they are reporting those extreme events. That's crucial, because there have always been fires and floods and droughts. Of course, all disasters cannot be connected to climate change, but many can. As the media begins to make that link for people, it helps solidify in people's minds that this is happening and it's not some far away, distant thing—it's tearing apart communities right here, right now, in the United States.

The other thing that happened was the release of two major scientific reports—the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] special report on what it would take to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming, which is a real wake-up call for the global community, saying that we've actually got about 12 years to very seriously bend the curves on our emissions if we are to have any hope of staying below 1.5 degrees. That got a fair amount of press coverage.

And the National Climate Assessment—the federal government report mandated to be released by Congress every four years—was also eye-opening about how climate change is affecting the United States now. The Trump administration tried to bury it by releasing it on the Friday after Thanksgiving, when people would pay the least attention to it. In this case everybody saw exactly what they were doing and it had the opposite effect. It seems to have created a perfect storm of media attention, and as a result Americans' awareness and concerns about this issue.

Who do you think has been good at drawing attention to climate change and its impacts, at connecting the dots?

I can give you two very clear examples. One is an effort called Climate Matters. We actually helped found it at the very beginning with George Mason University and then Climate Central and NOAA and NASA, and the American Meteorological Society and even the National Weather Association. It’s a project to empower broadcast meteorologists or weathercasters as climate change educators. That's been going on now for about eight years.

We know that most Americans get their news and information from local television. Not The New York Times, not Sierra magazine, sadly. The main reason we tune in to local television news is for the weather report, and weather is directly related to climate. It offers many opportunities to bring climate change up in a way that the other local stories don't.

We also know that weathercasters are very well liked in their communities, so these are trusted messengers. As a result we put together a network of weathercasters who are helping their local audiences connect the dots. When an extreme weather event happens, and it's appropriate to talk about it in the climate context, they will do so.

The other is a project we run called Yale Climate Connections. These are radio stories that are broadcast nationally on over 430 stations across the country, usually played twice a day, during morning and afternoon drive times. These are first-person stories of people all over America who are experiencing the impacts of climate change now and people who are rolling up their sleeves and taking action: a local mayor who is doing what they can to move to 100 percent clean energy, a doctor who is taking on this issue and trying to educate their patients. Americans need to hear and see from people who look like them, talk like them, share their values.

Speaking of mayors trying to do some good, Republican office holders are trying to move away from a narrative that climate change isn't happening to one of “Let's fix this or innovate within our belief system.” Does this affect how people perceive climate change, especially the group you call the ‘Dismissives’?

Yes, in fact. We've done lots of stories on Climate Connections about mayors and governors that are Republicans who are taking this issue on.

The evidence that we have indicates that the messenger is often more important than the message. If you're a conservative, hearing about climate change from someone that you do identify with, and that you do like and share political views with, then you're much more likely to say ‘Well, huh. Maybe this is a real problem.’ And then a conservative might say, ‘Well how do my conservative principles help solve this problem in a way that doesn't require bigger government and more regulation and all the things I don't like about Democrats?’

Does it happen the other way around too? Can voters influence their officials to change the way that they think about climate change?

Most elected officials wildly underestimate the amount of concern about and the support for action on climate change in their districts. They have no idea what their constituents actually think. They think they know because they talk to their friends, their lobbyists and their donors, and they try to assemble out of that limited set of information a picture of what their constituents do or don't want. But they are often wildly wrong.

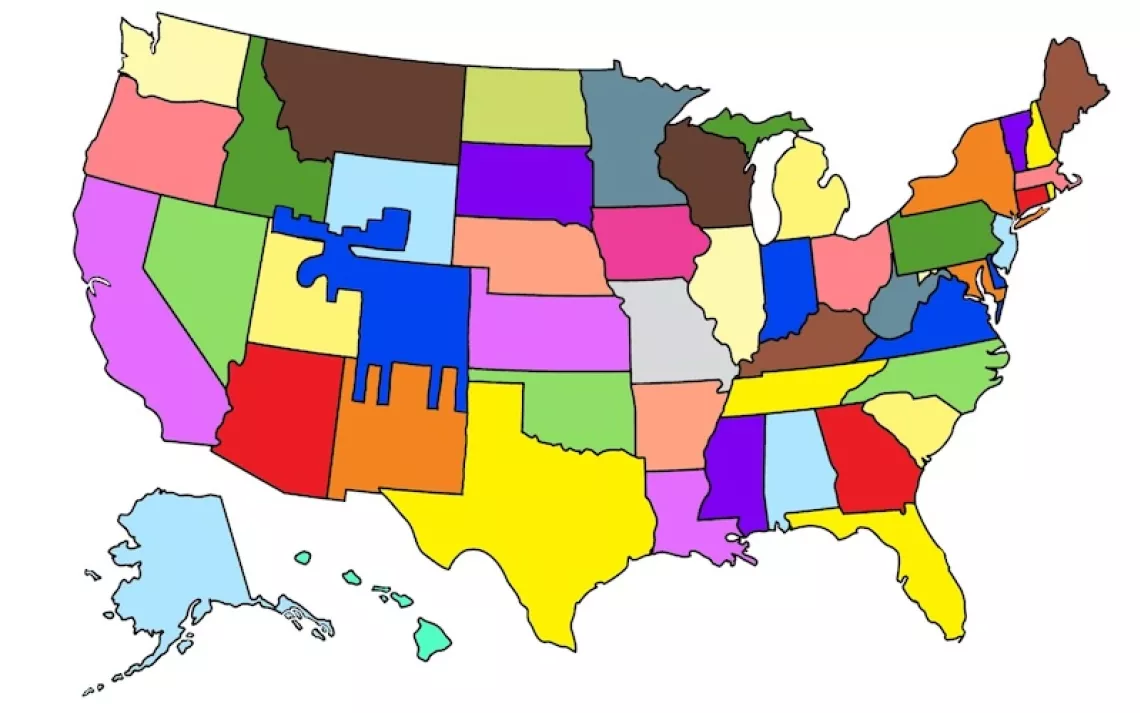

If you haven't seen it before, I'd encourage you to look at Yale Climate Opinion Maps. We've provided the state of public opinion about climate change and policy preferences and so on for all 3,000+ counties in America. So any elected official can very quickly see, “Here's what my constituents think.” There's a tremendous amount of gain to be had by simply giving elected officials the actual feedback from the maps. That's often a wake-up call.

Beyond that, I think what's desperately needed is citizen activists—Americans who are so passionate about this issue that they are willing to contact their elected officials and demand they act. This is one of the biggest missing pieces, but also a real opportunity for the environmental community—to empower and train their members to get actively involved in their local communities and put pressure on their own elected officials to take action.

You have said earlier that young people as a generation aren’t significantly more worried about climate change or intent on taking action. Do you still feel the same way?

We're tracking this, and historically we have not seen big differences between the generations. Youth will sometimes be higher on one measure and lower on another. There's not a clear pattern, with one exception. That is within Republicans.

Young Republicans are much more accepting of the reality of climate change, and are more supportive of action than are older Republicans. That's a generational split to pay attention to.

We have not looked at our most recent data across generational lines, so it's always possible that at some point we are going to see a much stronger generational difference. But up to now we have not seen it.

You've also done awareness research in other parts of the world, so compared with what you're seeing in America right now, with interest and worry spiking, do you see that happening across the world?

We haven’t done an international study lately. It’s been 10 years, but we partnered with a Gallup world poll to study this issue in 130 countries around the world (the single-largest and most sophisticated such study ever conducted). We found a few critical things that I strongly suspect have not changed that much.

First and foremost, four out of 10 adults on the planet had never heard of climate change. And that number would be as high as two-thirds or three-quarters of the population in particular countries like Egypt or Bangladesh. Bangladesh is often treated as a poster child of climate change vulnerability internationally, and yet most people in Bangladesh have never heard of it before.

We found in our in-depth study in India that two-thirds of Indians had never heard of climate change. But—and this is the critical thing—that does not mean that they are not keenly aware that the climate is changing. They know that, because these are societies that tend to still be subsistence-agriculture based. They are keenly aware of changes in precipitation, temperature, and weather patterns and are very worried about it. But they've never been introduced to the concept of climate change.

What we found in India is that even though most Indians had never heard of it, if we just give them a one-sentence description of how climate change affects weather patterns, immediately we had over 70 percent of Indians saying, "Yeah, that's happening and I'm very worried about it, and yes, I strongly support my government taking action to deal with it."

It's literally life or death for many of them, so this lack of awareness makes them even more vulnerable. They have their own theories of why the weather patterns are changing, but they don't have climate change to help them make sense of the changes that they're experiencing.

Even more importantly, they don't have climate change in mind as they think about what to plant and where to plant. They don’t know where to build their new cities and where to put schools and hospitals and roads. These are societies that are pouring scarce resources into building out their development, and if you're making decisions without climate change in mind, you are ever more vulnerable because the future is not going to be the same as the past or the present.

The US, along with Canada, Australia, and the UK are the hotspots of climate denialism. When you see the number of Americans understanding that climate change is happening is at 73 percent—an all-time high—that seems great until you see that in Japan it would be over 95 percent.

Another key thing about the international situation is that even though awareness of the issue is much higher in the rich countries, the perception of risk is much lower.

There are a lot of ways to try to solve climate change. Why pick communication?

Communication is a way to try to cross this enormous gap between the findings of climate science (which has been very sure that climate change is happening and that it's human caused and is already having very serious consequences around the world) and public understanding of those facts. The communication methods that scientists generally rely on, like peer-reviewed articles and scientific reports, are not read by the vast majority of people. Almost nobody in the lay public reads scientific articles.

So there's a huge science devoted to understanding how this communication works. What are the communication routes by which people do engage and do learn about these issues? The mass media is crucial; that's how most people even come to know about this. But it's also the way we communicate it among ourselves—among our friends, family members, coworkers, and then in the larger social, cultural, and political system.

Do you ever hear companies talking about climate change? Do you hear your religious or political leaders talking about climate change? Do you hear your doctor talk about climate change? Are they saying this is a real and serious problem, or are they saying this is a big, fat hoax?

When you start looking at how knowledge and understanding of an issue like climate change gets from the scientists—who are helping to figure out what this thing even is—to all of the rest of us, it’s a very complex process.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club