Water Conservation Is for the Birds

The arid west is facing a water crisis that threatens birds and other wildlife

Avocet | Photo courtesy of Melissa Groo/Audubon Photography Awards

In 2014, something that hadn’t occurred for almost 20 years took place in the Gulf of California: The 1,450-mile Colorado River reached the sea. For eight weeks, the billion–gallon “pulse” of water inundated the dried-out delta. Though the release was relatively short, it had a big impact, allowing new plants to germinate and increasing bird diversity in a very short time.

While letting a river run its course, even for a couple months, doesn’t sound like a particularly controversial move, in the arid areas of the American West, every drop of water is treated like liquid platinum. A new report from the Audubon Society called “Water and Birds in the Arid West: Habitats in Decline,” shines a light on how western water wars are impacting bird populations in two areas: the watershed of the Colorado River and the saline lakes that dot the basin-and-range country between the Sierras and the Rockies.

Water rights to the Colorado River have been in dispute throughout the last century, with agricultural interests and large developing cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas grabbing as much water as they can. And they need it. The river provides drinking water for 36 million people and waters over 5 million acres of land. The river has been heavily channelized and dammed to capture and use all that water. Groundwater has been pumped out of its watershed, and its banks have been logged.

The main consequence is a wholesale change in habitat. While the banks are naturally cottonwood-willow forests, over the decades those keystone trees have receded due to dropping groundwater levels and lack of flooding. In their place, flats covered in salt cedar, also known as tamarisk—an invasive plant whose roots can reach down much farther than native vegetation—have popped up. For birds, that reduction in habitat is proving difficult to manage. While riparian forests make up only 5 percent of the land cover in the U.S. Southwest, it provides habitat for 400 species of birds that breed in the region. The tamarisk provides some cover, but it can’t replace the varied habitat of the cottonwood forests.

Habitat degradation has pushed some species and subspecies to the brink, including the western yellow-billed cuckoo, southwestern willow flycatcher, and Yuma Ridgeway’s rail. The solution is to find more ways to share the water and restore more natural systems in the watershed. “If we don’t reserve some freshwater, the river can’t support native forests that rely on higher water tables and spring flooding events,” says Chad Wilsey, director of conservation science at National Audubon Society and the lead author of the study. “Then throw in the new element of climate change. Warmer temperatures mean more evaporation and less water moving through system, which compounds the threats. That’s really what we want to call attention to. We’re concerned with the impacts on birds and people, and we need solutions that work for both.”

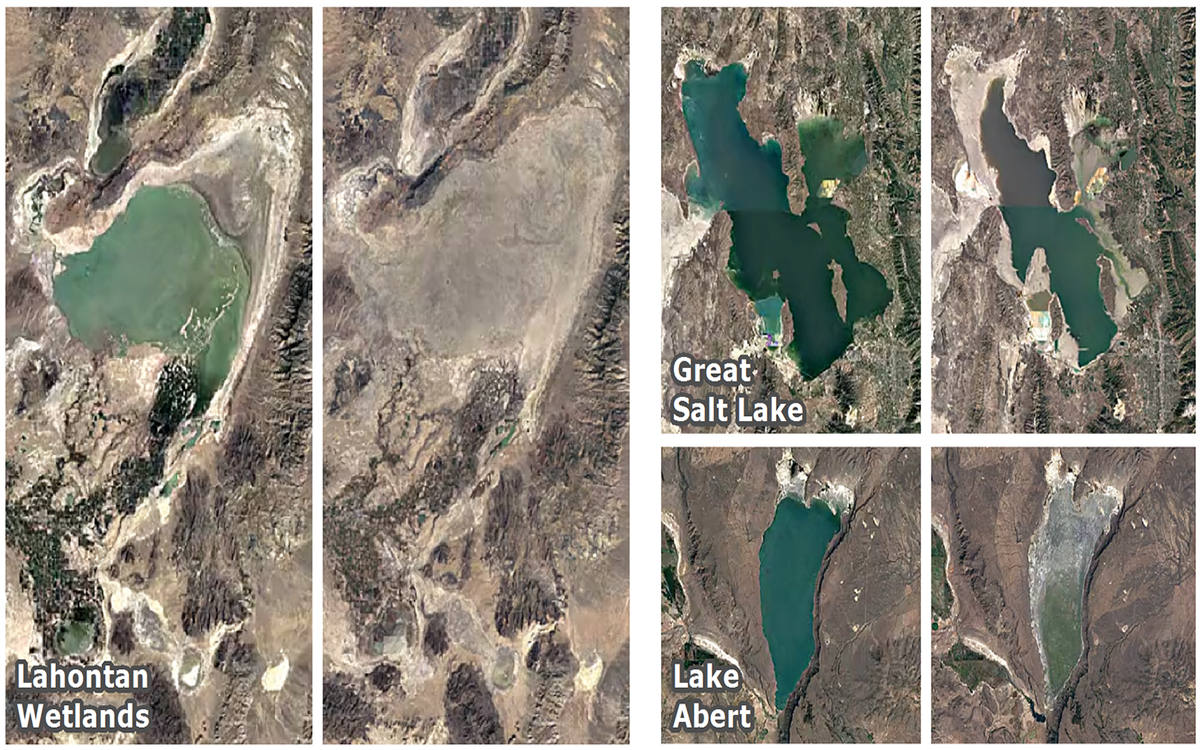

The Saline Lakes in 1985 versus 2015. | Courtesy of the National Audobon Society

While the impacts on western saline lakes are different, the threat to saline lakes in the intermountain west are the same: People are pulling too much water out of the tributaries that feed the lakes, causing some to diminish by 50 to 95 percent over the last 150 years.

Saline lakes are usually fed by mountain streams and rivers. Since they are terminal lakes with no outlet, arid soils accumulate in the lakes over time, leading to briny bodies of water like the Great Salt Lake, the Salton Sea, Lake Owen, Mono Lake, and Lake Abert. Typically, saline lakes are viewed as individual bodies of water, but the Audubon report encourages conservationists to look at them as a broader ecosystem connected by the birds that use them as stopover points during migration. For instance, 99 percent of the world’s eared grebes stop to feed on the lakes during their migration, as do 90 percent of the Wilson’s phalaropes and half the world’s American avocets.

Decreasing water levels in the lakes makes them saltier, changing the types of plants and fish that live in the lakes. Low lake levels also create land bridges to the islands where birds, like American white pelicans, breed. These bridges allow predators including coyotes to prey on these once-protected colonies.

Wilsey isn’t arguing that the lakes need to be completely refilled. Even modest amounts of water can help. “The freshwater in Owens Lake in California was entirely consumed,” Wilsey says. “Recently, managers were able to put some water back in the lake, and soon after, 100,000 birds were using it. Birds will use it if the water is there. We have to make choices now to share water instead of trying to bring the birds back after a lake has disappeared.”

One model for how saline lakes can be managed is Mono Lake, an otherworldly saline lake full of strange tufa spires on the eastern slope of the Sierras. In the 1970s, plans to divert water from Mono and other lakes in the area led to the creation of the Mono Lake Committee, which for 40 years has pushed to protect the lake and keep water levels at sustainable levels. “Saline lakes are often forgotten; they are unusual and don’t have the fishing constituencies that often advocate for other lakes,” says Geoff McQuilkin, executive director of the Mono Lake Committee. “But Mono developed a fan club of birdwatchers, photographers, and scientists studying the lake’s unusual chemistry early on.”

McQuilkin says other lakes have some catching up to do to build coalitions of people who advocate for their protection. He says one way Mono has succeeded is by appealing to urban dwellers and educating them about where their water comes from. Instead of taking a David-versus-Goliath approach, he says, the committee has come at the problem in a cooperative manner, looking for solutions that provide water to Los Angeles while also leaving enough to keep the lake’s ecosystems functioning. That has meant pushing for water conservation and recycling efforts in the city as well as finding ways to keep water in Mono’s tributaries. “Mono Lake protection is a story of changing outlooks on water resources in urban places,” says McQuilkin. “People don’t want to destroy a beautiful place if they don’t have to.”

While the successes at Mono are great, McQuilkin agrees with Audubon that the saline lakes need to be looked at and managed as a greater ecosystem. “The increase of eared grebes and what happens at Mono Lake matters. But what happens at the Salton Sea or Great Salt Lake or in Canada matters as well,” he says. “If we gave up all the other saline lakes, Mono would not be able to support all these systems on its own.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club