The Stogie-Chomping Daredevil Warrior for Wilderness

100 years on, we could use more Martin Littons

Threading the needle’s eye of Navajo Bridge on the Colorado River near Lees Ferry in his vintage Cessna, with Sierra Club icon David Brower riding shotgun, was typical of Martin Litton’s approach to almost everything. “This plane doesn’t fly fast enough to hurt anybody,” Litton once assured another passenger, as he changed the film in his camera to take pictures of the site for California’s proposed Diablo Canyon reactor while keeping his plane on a steep, steady climb to free his hands.

Threading the needle’s eye of Navajo Bridge on the Colorado River near Lees Ferry in his vintage Cessna, with Sierra Club icon David Brower riding shotgun, was typical of Martin Litton’s approach to almost everything. “This plane doesn’t fly fast enough to hurt anybody,” Litton once assured another passenger, as he changed the film in his camera to take pictures of the site for California’s proposed Diablo Canyon reactor while keeping his plane on a steep, steady climb to free his hands.

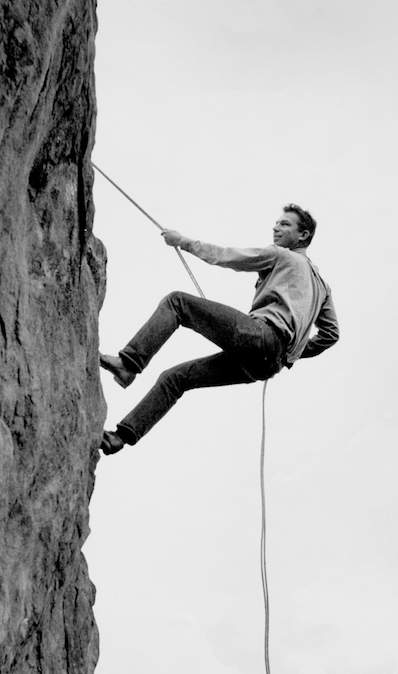

Litton died in 2014; this year would have been his centennial. All of his grand passions took shape in the first quarter of his life: his love for flying, photography, rowing boats, wild places, and writing, and for stirring things up. The man who in later years looked like a Roman senator earned his wings the hard way, rattled by shrapnel from German anti-aircraft guns and crash-landing gliders behind enemy lines in the Netherlands, earning an Air Medal in the process.

In the decades that followed, Litton took part in some of the 20th century’s largest conservation battles. He never hesitated to censure the government of the country whose uniform he had worn and for which he had risked so much. In fact, the destruction and death he witnessed overseas may have spiked Litton’s zeal to protect his nation’s natural heritage; they certainly honed his derring-do and endurance.

John Muir’s “Range of Light”—California’s Sierra Nevada—kindled the native Los Angeleno’s blazing love for wilderness. As teens, Litton and a friend rented a burro for 75 cents a day and climbed Mt. Whitney on a 12-day wilderness trip. The experience, he later recalled, changed his life. In 1935, at age 18, he was already protesting the depletion of Mono Lake by water-guzzling L.A. He launched his first environmental crusade as a UCLA student, forming California Trails, which sought to keep roads out of his beloved mountain range. The group prevented a highway from slicing through the High Sierra in what later became the Golden Trout Wilderness. But no issue was too insignificant for the young scrapper; he was nicknamed “Mr. Litterbug” for a scathing Los Angeles Times editorial that decried citizens tossing garbage alongside their highways.

Though he referred to studying Chaucer at UCLA as just “another idiotic activity,” Litton graduated with a B.A. in English in 1938. It helped sharpen his gift for language, with which he would skewer his foes for decades. Into his nineties, he was a gifted raconteur, fascinating audiences with a voice like smooth gravel. At UCLA, he also rowed crew, bulking up physically and steering toward a livelihood made in Class V rapids. Even as a young man, Litton already was, in the words of river guide Kevin Fedarko, “a force of nature that recognized no one’s authority and tended to go tearing off in bizarre directions.”

In 1952, Litton floated the Yampa and Green Rivers through Dinosaur National Monument, whose rapids and redrock solitude hooked him. The monument’s manager had invited the daredevil muckraker, as dam projects threatened the rivers at Echo Park and Split Mountain. After the trip, then-Sierra Club president Dave Brower convinced Litton to join the fight to foil the Bureau of Reclamation’s dam-building plans. Brower also recommended Litton for the job of travel editor at Sunset magazine in 1954, from which perch Litton spearheaded efforts to preserve California’s old-growth forests, as in his 1960 magazine story "The Redwood Country."

And in 1955, he first boated the Grand Canyon at a time when fewer than 200 people had completed the journey pioneered by John Wesley Powell.

Litton was elected to the Sierra Club’s board of directors in 1964, while Brower was executive director. “When I would waver in various conservation battles,” Brower reminisced, Litton “would put a little starch in my backbone by reminding me that we should not be trying to dicker and maneuver.” Litton’s brash approach did not even spare fellow club members—he once called Ansel Adams a “dumbhead” and would sometimes puff on stogies during board meetings just to annoy.

Yet the projects Litton helped thwart read like a Baedeker of Western atrocities—and the victories set legal precedents. In the 1960s, he rallied the Club to defeat Disney’s Mineral King ski resort in the Sierra and two dams in the Grand Canyon, just as it had at Dinosaur in the '50s. “Shall we fail to go into battle because it is hard to win?” Litton asked in Sierra’s predecessor, the Sierra Club Bulletin. Controversy didn’t slow him down; it energized him.

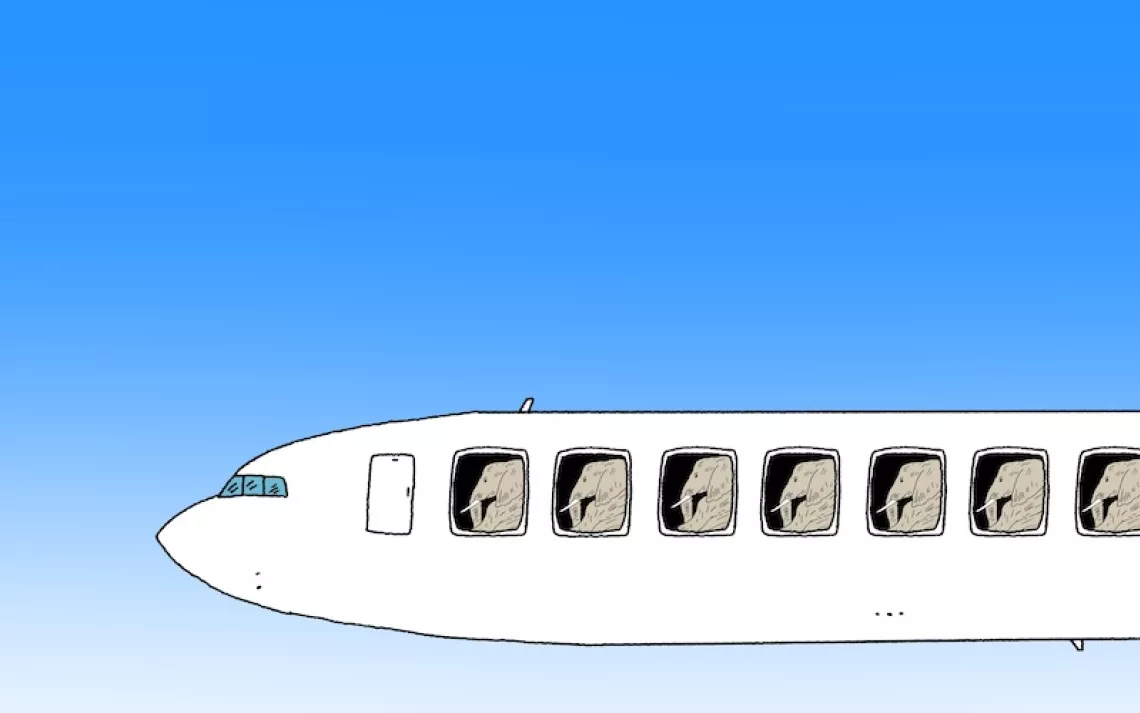

In 1969, Litton started a successful business offering trips by dory down the Grand Canyon. He adapted the original Oregon “drift boat” design to the Colorado River’s conditions, creating beautifully handcrafted, rather fragile wooden vessels that “belong on big waves.” He named each one after a place sacrificed to “progress”—Hetch Hetchy, Peace River, Roaring Springs, Music Temple—a custom Grand Canyon Dories follows to this day. A reminder of elegant shipwright traditions, this fleet of holdouts bucked the trend of inflatable rubber rafts that were even then taking over the canyon. No wizard as an oarsman, Litton compensated in typical fashion with enthusiasm. Not trusting his crew, he once piloted three dories on separate runs through Crystal Rapids—and flipped all three.

One of Litton’s greatest regrets—one he shared with Brower until their deaths—was the concession the Sierra Club made to not oppose the Glen Canyon Dam in exchange for the cancellation of Dinosaur’s dams. In later years, he backed the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance and Glen Canyon Institute in trying to restore the gem that “Lake” Powell had drowned. His efforts to protect California old growth met with better success, culminating in 2000 when President Bill Clinton established Giant Sequoia National Monument. Even so, in 2001, Litton founded the nonprofit Sequoia ForestKeeper to battle the U.S. Forest Service over trees Litton felt were being cut too nonchalantly to reduce fire risks.

Merging two lifelong passions, Litton ran his last river trip at age 92, as a Sequoia ForestKeeper fundraiser, making him the oldest person to ever row a dory in the Grand Canyon. He downplayed whitewater—and, implicitly, his whole career—saying, “What’s heroic about having a good time?” Yet anyone floating past the shafts drilled into the Grand Canyon’s cliffs as probes for a dam will appreciate his achievements.

This post has been corrected.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club