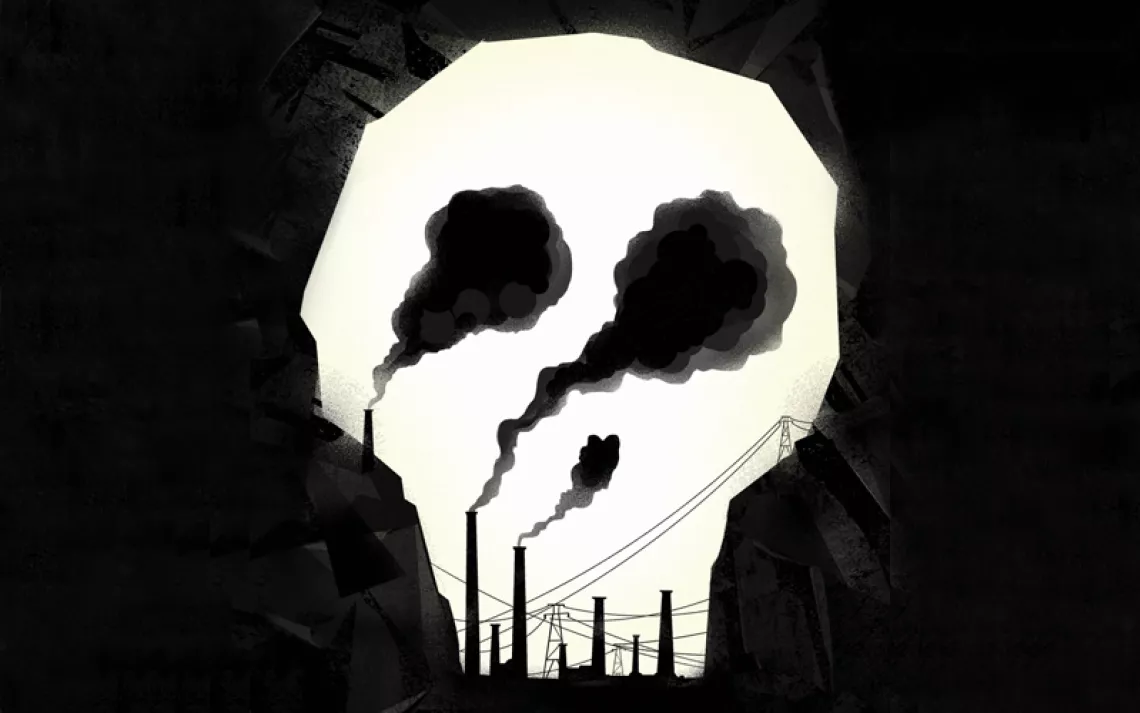

Stick a Fork in This Coal Terminal—It’s Done

Citizens of Plaquemines Parish win a battle, if not the war

Audrey Trufant-Salvant | Photo courtesy of Tyronne Edwards

A proposed coal-export terminal that communities in coastal Louisiana have been fighting since 2013 is finally dead. “Many times, we were told the RAM coal-export terminal was a ‘done deal,’” says Audrey Trufant-Salvant, a Plaquemines Parish councilmember. “And now it’s done.”

In 2015, Trufant-Salvant hammered one of the first nails in the coal terminal’s coffin when she convinced her fellow councilmembers to deny RAM Terminals LLC a building permit. The terminal’s uncovered 80-foot coal piles would have blown toxic dust into Ironton, the historic African American community where Trufant-Salvant lives. (You can read the backstory in Sierra's May/June 2015 issue.)

That was not the end of the story, however. In March 2016, RAM Terminals’ project seemed to regain momentum when the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources granted the company a coastal use permit. A coalition of more than 200 concerned locals—including members of the Sierra Club Delta Chapter, the Gulf Restoration Network, and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network—quickly mobilized to apply public pressure. Within a month, Louisiana DNR withdrew its permit.

After that, the fix was in. RAM’s Army Corps of Engineers permit required it to either complete the building of the project or ask for an extension by November 30, 2017. The company did neither and so the terminal died. RAM did not respond to a request for comment.

RAM’s defeat bodes well for a $1.3 billion coastal restoration project in Louisiana's coastal restoration plan. Every hour, the state loses a football field of land due to the oil and gas industry's drilling and dredging footprint, Mississippi River levees and sea level rise. The coal terminal would have occupied a key coastal site and would have reduced the efficiency of the state’s priority restoration project by as much as 17 percent, according to a study by the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

For Ironton residents, the fight for environmental justice isn’t over. Now another energy company, Denver and Beijing–based IGP, is proposing to build the world’s largest methanol complex three miles downriver from the town. Some fear that a chemical plant in a hurricane zone may create an explosion risk. Just last year, the Arkema plant in Crosby, Texas, exploded twice when Hurricane Harvey’s floodwaters caused the facility to lose power, allowing its volatile chemicals to warm to dangerous temperatures. Trufant-Salvant says that the proposed methanol plant is yet another chapter in southern Louisiana’s history of environmental racism. “It’s not a coincidence that all these industries keep trying to build next to black communities,” she says.

Grace Morris, an organizer with the Sierra Club’s Coast Not Coal campaign, credits the RAM threat for helping mobilize a coalition of hard-working residents, public officials, and environmental activists who are now prepared to swiftly respond to new threats, including the methanol plant. “This was never about just one fight,” she says. “This was about coming together and building strength for the next fight and then the next fight, which will inevitably come.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club