Hawaii Leads on Climate in the Trump Era

The island state leads the way as regional governments take action

Photo by jewhyte/iStock

On June 6, just days after the Trump administration announced it would pull the United States out of the Paris Agreement, Hawaii took a bold step in the opposite direction—it doubled down on climate leadership. Before an enthusiastic gathering of state representatives, activists, and supporters in the outdoor capitol rotunda, Governor David Ige signed two bills that ratified and extended his state’s commitment to environmental stewardship. One bill, SB 559, adopted elements of the Paris accord as state law, making Hawaii the first state to do so. The other, HB 1578, established a plan to create a task force dedicated to promoting climate-friendly agricultural practices.

The audience of about 100 was larger than usual for a public-bill-signing ceremony in Honolulu. “People took interest because it was a turning point in the discussion of what we’re going to do post-Paris, as a state and as a country” said Representative Chris Lee, who introduced HB 1578 to the state assembly earlier in the year.

The island state isn’t alone in its efforts to guide the country forward. In the absence of federal action, many regional governments across the United States are stepping up as leaders in the global effort to mitigate climate change. California, with its cap-and-trade system and aggressive emissions targets, is often cited as the standard-bearer for state-level climate action.

Hawaii has earned the right to share that mantle with its neighbor across the Pacific. Thanks in part to a handful of bills passed earlier in the decade that promote clean transportation, the state is second to California in electric vehicle adoption per capita. In 2015, the state legislature established the boldest clean energy goal of any state in the nation—100 percent renewable electricity by 2045—a target made even more aggressive by Hawaii’s status as the most fossil-fuel-dependent state. “Hawaii is happy to serve as the poster child to the world in terms of sustainable holistic climate policy,” said Marti Townsend, director of the state’s Sierra Club chapter.

Why has Hawaii become such a forward-thinking state on climate action? The answer is varied and complicated, but the two bills passed in June provide a clue.

SB 559, which adopted measures of the Paris Agreement as state law, was introduced by Senator J Kalani English the day of President Trump’s inauguration. Reflecting on the possibility that Trump would withdraw the United States from the Paris accord, the final version of the bill reads, “Regardless of federal action, the legislature supports the goals of the Paris Agreement to combat climate change and its effects on environments, economies, and communities around the world.” When Trump followed through on his promise, regional governments throughout the country pledged to uphold the agreement anyway. With the signing of SB 559 on June 6, Hawaii became the first state to actually put that pledge on the books.

SB 559 exemplifies the state’s long-standing commitment to taking part in a global solution to climate change. That dedication is also motivated by the unique threat that high greenhouse gas levels pose to island societies like Hawaii. “Climate change is a real thing, and it poses an immediate and long-term threat to Hawaii’s economy, security, and way of life,” Townsend said.

Rising sea levels, temperatures, and diminishing rainfall are among these imminent threats, some of which are already happening now. This year, Hawaiian coastlines have experienced their highest tides on record since 1905. “We’re feeling the effects of the climate change already,” Representative Lee said. “We don’t feel a debate.”

The other bill signed on June 6 is a product of Hawaii’s mission to provide climate-minded solutions to the state’s economic issues. Hawaii is at an economic turning point as it seeks to become more self-sufficient. Along with its long-standing dependence on fossil fuels from outside the state, Hawaii also relies on imports for 80 to 90 percent of the food it consumes. The islands are a great place for farming and ranching, but historically most of their cultivable soils have been populated by cash crops grown for export. These monocultures of sugarcane and pineapple are now becoming things of the past, leaving large swaths of land open to different forms of agriculture. “The last sugar plantation closed December of last year, and we’re in the process now of trying to diversify our agricultural economy to ensure we actually have local food production,” Townsend said.

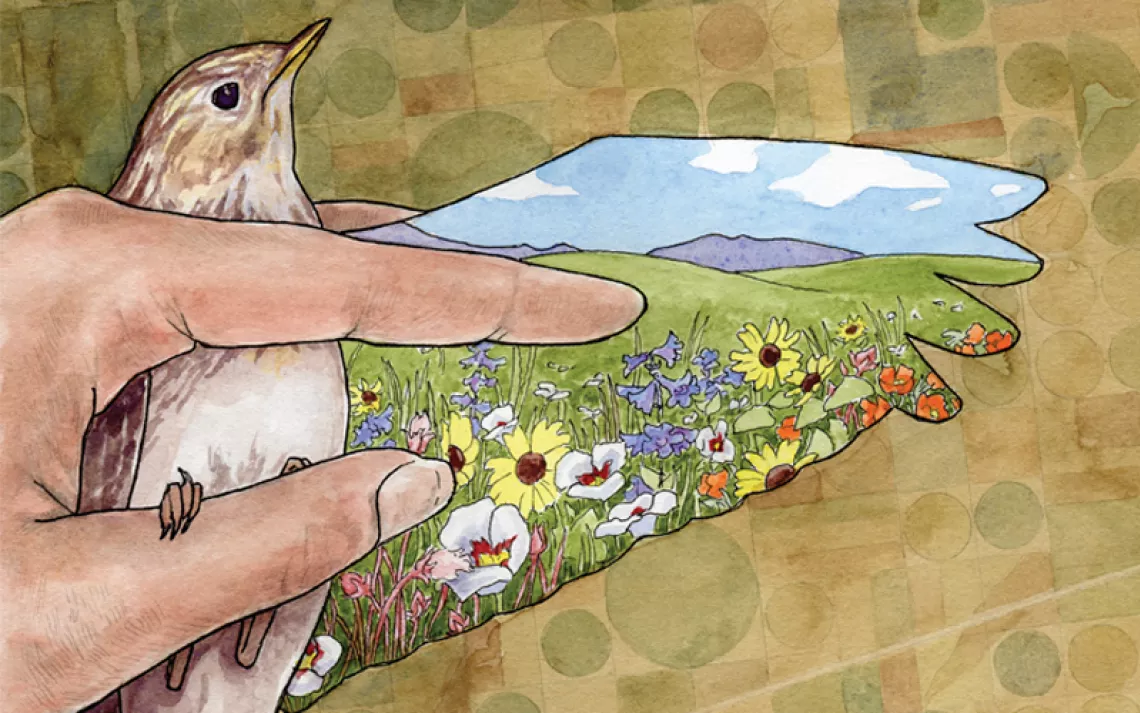

The “carbon farming” task force established by HB 1578 will look to create a sustainable—perhaps even carbon-negative—way forward for Hawaii’s agricultural economy. The principles of “carbon farming” begin with the basics of photosynthesis—plants get their nutrients by capturing CO2 through their leaves and converting it to a form of carbon they can use for energy. Excess carbon they don’t need is pumped through their roots and eventually gets stored in the soil below. Soil often acts as a carbon “sink,” storing underground large amounts of carbon that would otherwise remain in the atmosphere as CO2.

Modern agricultural methods often disrupt soil and release its stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Carbon farming is a set of holistic land-management practices designed to keep that carbon in the ground. Its benefits are twofold, the first of which is based on the simple fact that higher carbon content makes for healthier soils. Soil is degrading and eroding at an increasing rate throughout the world due to industrial agriculture, and many governments have looked to carbon farming practices as a possible remedy. The task force established by HB 1578 will work with local ranchers and farmers to figure out how these practices can help alleviate the specific issues they face. “There are some good models in other states, other countries that we can look toward, but having this regional focus really looks toward our own communities,” said Rebecca Ryals, a professor of ecology at the University of Hawaii, about the bill.

The other major upshot of carbon farming is its potential to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Some scientists see it as a promising fix to climate change—one Ohio State researcher estimated that restoring degraded soils worldwide could result in the sequestration of 35 percent of annual global CO2 emissions caused by the burning of fossil fuels. “What you do on the farm will affect the whole globe,” Ryals said.

With this range of benefits in mind, Marti Townsend called HB 1578 a win-win for Hawaiians. “It captures carbon from the environment, it makes our soils healthier and more productive, and it also helps to advance our sustainable agricultural goals of growing our own food,” she said. Representative Lee also spoke of the bill’s wide appeal. “We’ve already proven we can debunk the myth that we have to sacrifice economic success in order to protect our climate.”

Hawaii’s economic predicaments and the climate threats it faces are particular to the state—to a degree, so are those encountered by every regional government—but the way it approaches both serves as a model of strong climate leadership. “We’re a model for what you can be and what can happen in Washington,” said Representative Lee.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club