5 Ways Not to Kill Cyclists

Drivers! Avoid dents and scratches—and vehicular manslaughter charges—by following these simple tips

Cycling in the street | Photo by TommL/iStock

In 2014, the latest year for which data is available, 726 cyclists were killed in collisions with motor vehicles in the United States. There are, of course, things that cyclists can do to avoid joining this grim statistic—not riding at night without lights and while dressed in dark clothes springs to mind. But drivers of two-ton hunks of speeding metal clearly have a major responsibility in not killing those with whom they share the road. Here are five simple strategies every driver should employ.

1. See cyclists

The classic response of motorists who strike cyclists is something in the order of “But officer, I didn’t see her! She just came out of nowhere!” As noted in a Houston Press analysis of bike crashes in the Houston area, almost all drivers, if they gave a statement to the police, said they just didn’t see the cyclist at all or in time to avoid hitting him or her. The reports then generated by police almost always reflect the driver’s account, and with the cyclist no longer alive, often there is little to counter that version of events.

“Motorists need to see cyclists,” says Steve Taylor, communications director of the League of American Bicyclists. “Be aware that cyclists are in the road, and that they have a right to be in the road. That is one of the biggest things that motorists do not realize: Cyclists have every bit as much right to be in the road as they do. And, depending on the situation, they can be in the middle of the road. Cyclists are real vehicles.”

2. Allow three feet when passing

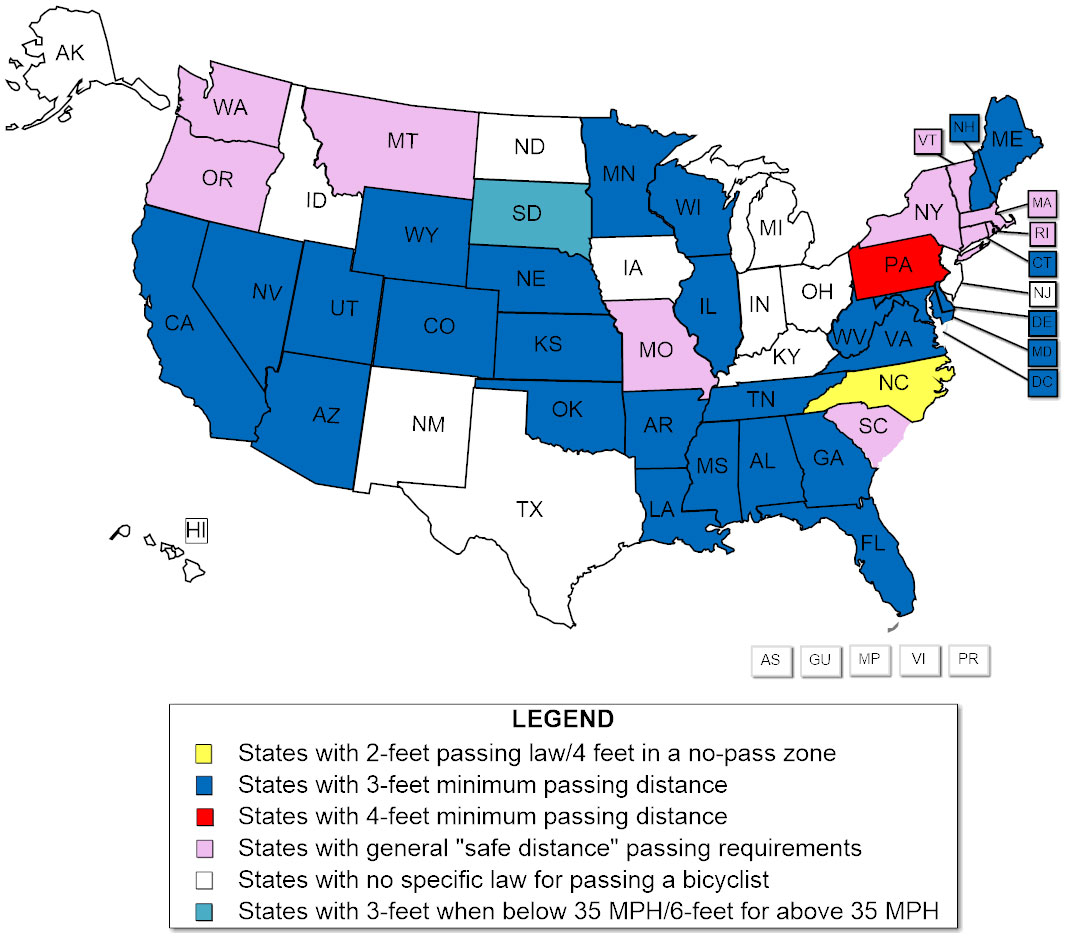

If cyclists are real vehicles, it follows that motorists need to share the road with them. (Those “Share the Road” signs, however, are going out of fashion, because it turned out that many motorists took them as a directive to cyclists that they should get the hell out of the way. Many are now being replaced with far more useful “Bicycles May Use Full Lane” signs.) That means that drivers can only pass when it is safe to do so. In fact, roughly half the states require that vehicles pass cyclists at least three feet away:

Photo courtesy of National Conference of State Legislatures

(In case motorists are unclear on how far three feet—OK, one meter—is, this guy employs a pool noodle to show them.)

It’s important to note, says the League of American Bicyclists’ Taylor, that states with such laws generally allow motorists to cross double yellow lines in order to pass cyclists safely. Be sure you have clear sight lines, though—crossing into the opposing lane around a blind curve is just asking for trouble.

3. Use the “Dutch reach”

Car drivers can kill or maim cyclists even after the engine is off, when they open their doors in the path of an oncoming bicycle—a hazard known to cyclists as “dooring.” The impact often throws the cyclist into the adjoining lane, where they can be run over by passing traffic.

Drivers can avoid this hazard through an ingenious method known as the “Dutch reach” (so called because it is supposedly included in Dutch driving tests). When getting out of your car, instead of opening the door with your left hand, reach around with the right. This forces you to turn your head—and to see if any cyclists are approaching. Here’s a primer, from our friends at Outside:

4. Advocate for protected bike lanes

Motorists wouldn’t have to worry about safely passing or dooring cyclists if the cyclists had their very own lane of traffic separate from that used by motorized vehicles. These are called protected bike lanes, and they’re what makes cycling in countries like Denmark so popular and enjoyable. They generally run next to sidewalks and are physically separated from car lanes by parked cars or some other barrier. Danish ones look like this:

Photo courtesy of Streetsblog.org

And the newly installed ones in Oakland, California, look like this:

Photo by Paul Rauber

There’s no problem with passing, no problem with dooring (on the driver’s side, at least), and the only time the cyclist has to enter the main roadway is to turn left. I ride on one daily commuting to Sierra’s Oakland office and can attest that it is remarkably liberating to ride free of fear of vehicular assault.

5. Leave your car behind

One of the most important determinants of cycling safety is numbers: The more cyclists there are, the more motorists are aware of them, and the safer everyone is. Cycling infrastructure—like the protected bike lanes above—attracts many otherwise risk-averse riders, including older people and parents with children. Motorists benefit as well, Taylor points out: By narrowing the roadway, protected bike lanes lower the top speeds for motorists. “That doesn’t mean that a safe driver gets there more slowly; it means that unsafe drivers tend to drive more slowly. It’s not taking away from motorists.”

So drivers, put down your keys and pick up a bike helmet. The safest car is the one that’s parked in the driveway.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club