Public Lands Belong to All of Us

The public lands of the West aren't the exclusive property of ranchers, loggers, and miners

This summer, taking advantage of one of the more monarchical powers provided to his office, Donald Trump pardoned Dwight and Steven Hammond, a father-son pair serving time in federal prison for repeatedly setting fire to federal lands in Oregon. Unlike some of Trump's other pardon recipients, such as former Maricopa County sheriff Joe Arpaio (found in contempt of court for unreasonable searches of undocumented immigrants) and Scooter Libby (the Bush administration official who illegally leaked the identity of a covert CIA officer), the Hammonds aren't national figures. They are, however, considered heroes among the ranks of anti–federal government insurrectionists. The 2016 armed takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon was, in part, a protest over the imprisonment of the Hammonds.

The Hammonds' serial arson and the Malheur occupation may seem like the outbursts of a handful of nutjobs. But such extremist views vein the American West. A High Country News investigation found that, between 2010 and 2014, federal public lands employees in the West experienced dozens of assaults and threats. This aggression is fueled by a deep-seated belief—however ahistorical and legally unfounded—that the federal government has no claim to public lands. All too often, the lawbreakers' arguments are echoed by lawmakers. In 2012, the Utah legislature passed a bill demanding that the U.S. government transfer control of 31 million acres of federal lands within the Beehive State. Similar bills have been introduced or passed by the legislatures of Arizona, Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming.

Antipathy to federal land ownership has now reached the very pinnacle of the federal government. At the signing ceremony for his executive order dismantling Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monuments, President Trump said his goal was "to reverse federal overreach and to restore the rights of this land to your citizens." (Read more about this sorry saga in our cover story, "Land Grab.") Downsizing the monuments, Trump claimed, would give control to "the communities that know the land best and cherish the lands best."

But this line of thinking misses a key point: Public lands belong to all Americans, not just those who live closest to them.

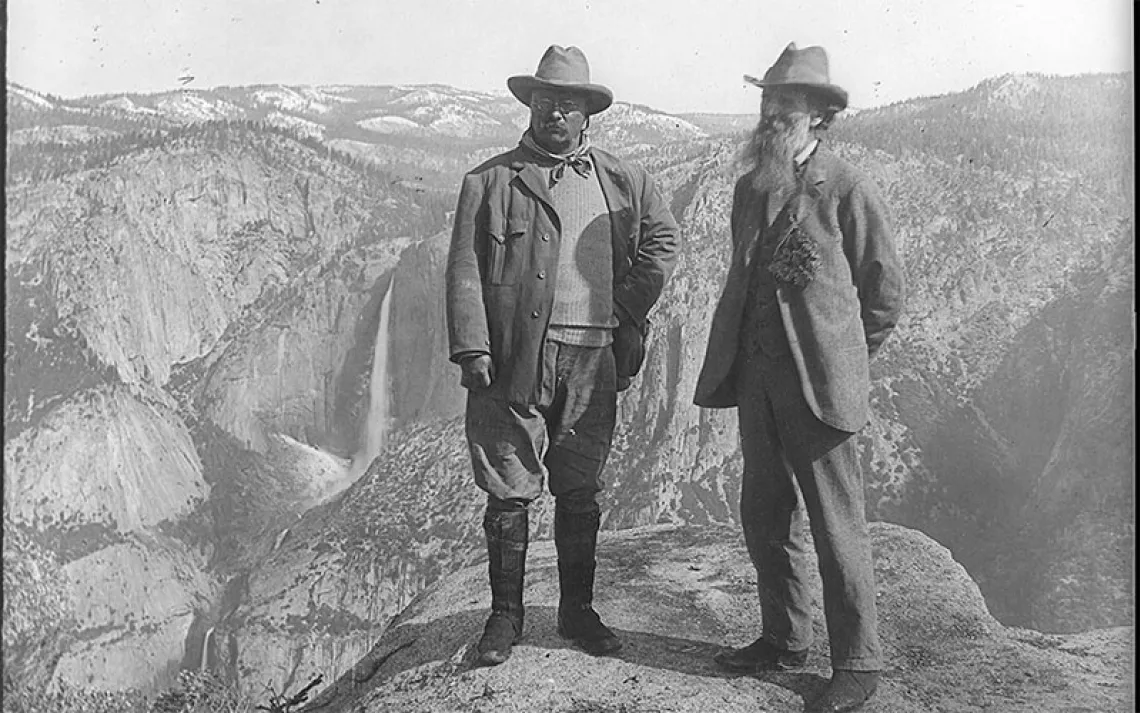

The vast public acreage of the West isn't the exclusive property of ranchers, loggers, and miners. A resident of, say, Michigan has as much ownership of federal lands in Utah as a Utahan. Similarly, New Yorkers don't hold a monopoly on the Statue of Liberty, nor do Californians have the only say in how Yosemite National Park is managed. While the residents of Michigan, Utah, New York, and California might have different ideas about how best to manage federal lands, such disagreements are part of the hurly-burly of democracy.

By insisting that Americans don't have an equal stake in our shared lands, Trump weakens the values of solidarity and collective interest that undergird citizenship. In his worldview, there is no commonwealth, only private interests. The Hammonds and the other sagebrush rebels aren't merely torching the ideal of public lands—they are also trying to set fire to the bonds that link together a republic. The president is helping to fan the flames.

This article appeared in the September/October 2018 edition with the headline "Public Lands Belong to All of Us."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club