The Best Eco-Conscious Books for a Summer Read

Here are six books that will inspire you to think, and act, differently

Photo by BongkarnThanyakij/iStock

The end of summer may be in sight, but it's not over yet. Whether you're hitting the trail, going to the beach, or just heading to your favorite cafe on a Sunday afternoon, consider taking along one of these excellent books to get your brain gears turning.

—Sierra staff

Nature’s Allies

Nature’s Allies

Eight Conservationists Who Changed Our World

By Larry A. Nielsen

Island Press, August 2017

—Jason Mark, editor in chief

OK, I’ll admit that a joint biography of eight leading conservationists isn’t most people’s idea of beach reading. But maybe your idea of a beach is a pebbled one on a gravel-bar river in the mountains, some place where the epic trees make it seem natural to consider the length of history.

If so, then bring along Larry A. Nielsen’s Nature’s Allies, a fine primer on some of the most inspirational figures in the history of the environmental movement. Nielsen, dean of the College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University, has the command of a practiced lecturer, and his biographical sketches of famous environmentalists zip by like NatGeo profiles. He covers the canonical—Muir, Leopold, Carson—and also has the good sense to get out of North America—there’s Chico Mendes and Wangari Maathai, too. Nielsen’s narratives are quick, the result of deep study distilled, and he uncovers some gems. I love this Aldo Leopold quote, from a manuscript titled “Erosion and Prosperity”:

All civilization is basically dependent upon natural resources. All natural resources, except only subterranean minerals, are soils or derivatives of soil. Farms, ranges, crops and livestock, forests, irrigation, water, and even water power resolve themselves into questions of soil. Soil is therefore the basic natural resource.

That’s the clarity of a philosopher who trained in the forest.

I especially appreciated Nielsen’s profile of the Nisqually activist Billy Frank Jr., who in the 1970s staged a kind of performative civil disobedience by fishing and hunting in a national park that had been his ancestors’ territory. I had known Frank’s story before the book, but in the wake of the Standing Rock resistance, Nielsen’s telling took on fresh meaning. Billy Frank Jr.—more than Russell Means or Dennis Banks—seems to be the clearest precursor of today’s resurgent Native American nationalism, with its social-media-savvy activists constantly culture-jamming the white man.

My favorite story in Nature’s Allies is that of Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling. Ding Darling was an Iowa editorial cartoonist whose plain line drawings and one-line captions were to the telegraph-driven newspapers of a century ago what BuzzFeed articles are to today’s social media—they were everywhere. Darling’s national media fame led to a friendship with President Herbert Hoover, who became a fishing pal. As a Republican, Darling hated Roosevelt. But he loved birds, and fish, and trees more, and when FDR called him to serve, Darling went to Washington, D.C., to head the Biological Survey (today’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Darling surfed the wave of New Deal ambition to dramatically expand the wildlife refuge system. He hired a young aide, John Sayler III, who in the space of a summer drove 18,000 miles across the country in a government sedan and, armed with a government checkbook, purchased hundreds of thousands of acres of wetland, marsh, saltwater estuary, and woods where birds nested. During Darling’s brief tenure, 55 new wildlife refuges were established. Then he quit D.C. and went back to Iowa (and later cofounded the National Wildlife Federation).

I like Darling’s plain-spokenness. “All it takes to be a conservationist is to have been awake and a witness to what has happened to all of our continental forests, soils, waters, minerals, and wildlife in the last 50 or 75 years.” I think the environmental movement could use a few more Iowa Republicans. You can probably still find some of them fishing those gravel-bar rivers.

Quakeland

Quakeland

On the Road to America’s Next Devastating Earthquake

By Kathryn Miles

Dutton, August 2017

—Katie O’Reilly, adventure + lifestyle editor

“No matter where you’re reading this book, there’s a good chance you could throw a rock and hit a fault,” writes science journalist Kathryn Miles in Quakeland. “What’s even more disturbing is the recent revelation that we don’t even really need active faults to produce earthquakes: As it turns out, we’re pretty good at doing it ourselves.”

The eminently disaster-literate Miles, the author of 2014’s Superstorm: Nine Days Inside Hurricane Sandy, goes on to detail how oil extraction, wastewater extraction, dams and reservoirs, and even the construction of high rises, can induce tremors. Many of them are sufficiently seismic for the U.S. Geological Survey to add them to its hazard maps, which now list more than 2,100 known faults—an all-time high.

If a wide-ranging account of the least understood of natural disasters—complete with doomsday warnings and detailed stories of the havoc earthquakes wreak—doesn’t exactly conjure summer vacation, know that this was my first thought, too. Quakeland, however, is also a road trip story. And along the quake-chasing road to California’s dams, Idaho’s mines, the banks of the seismically affected Mississippi River in Memphis, and the cracked terrain of fracking-ravaged Oklahoma and Texas, Miles makes for a personable, adventurous, and witty companion—describing unstable ground as a rapidly melting Dairy Queen Blizzard and introducing readers to colorful geologists, one of whom tells a room full of devoted Baptists worried about earthquakes that they’re all screwed.

Miles establishes quick rapport with engineers, first-responders, and people living beneath toppled chimneys, and finagles her way into mines, dams, and nuclear power plants built atop tectonic plates. What she learns lends bite to your dog day reading—our infrastructure is largely ill-equipped for our seismic reality, which is that as the population and rates of development mount, so does our earthquake risk. But her vivid retellings of earthquakes in the near and distant past serve a purpose—to relay “how fragile—and volatile—the ground beneath our feet really is.”

Thanks largely to Miles’s conversational, somehow cheery writing style, I was riveted throughout and heartily recommend this book to people living everywhere. For policymakers, Quakeland should be required reading.

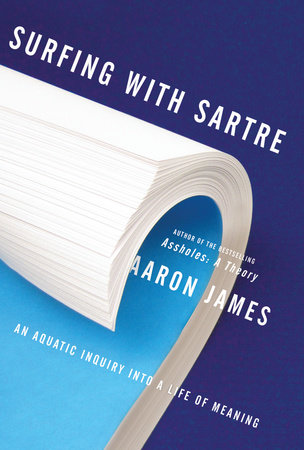

Surfing with Sartre

Surfing with Sartre

An Aquatic Inquiry Into a Life of Meaning

By Aaron James

Doubleday, August 2017

—Jonathan Hahn, managing editor

What can surfing teach us about politics, work, and freedom of choice, everyday getting around in the world, and even climate change? Turns out quite a lot, according to Aaron James, a professor of philosophy at the University of California, Irvine, and author of the new book Surfing with Sartre: An Aquatic Inquiry Into a Life of Meaning.

James is known for mapping philosophical inquiry onto cultural touchpoints in ways that make dense theory accessible to the lay reader (see his heady and often hilarious theory of social relations via “asshole studies” in Assholes: A Theory). Surfing with Sartre, however, is not only a fun and informative read, it’s also an important achievement in the way it draws together phenomenology and existentialism with a fresh look at some of the most serious ills plaguing modern life today—all told through a surfer theory of how to work less and be stoked more, and in so doing, make the world a more sustainable place. If it sounds silly, it’s not: Surfing with Sartre recalls the zen glories of Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Hubert Dreyfus's and Sean Dorrance Kelly's All Things Shining with the uberdude axioms of Point Break and The Big Lebowski. This is Nietzsche on a surfboard, and it's an epic ride.

There is an entrenched and dangerous malady of disconnection that defines our contemporary moment, James wants to contest. Disconnection—or to put it more precisely, lack of attunement—defines modern life, whether it is a disconnect between work life and leisure life, between industrial societies and the environment those societies are exploiting, between computer screens and the world those screens are supposedly making more accessible. We are out of tune with nature, with leisure, with each other. Climate change ends up being as much a symptom of the 40-hour workweek as the blind greed of ecological exploitation. “The old-style capitalism put us out of attunement with the world’s available resources,” he writes.

Enter: surfer-being.

A theory of attunement is exactly what James—an avid surfer—is after here, and the surfer serves as a heroic foil against which all that is wrong with our beleaguered modern moment can be compared. “Being adaptively attuned to a changing natural phenomenon, in part by not needing to control it, is at once a kind of freedom, self-transcendence, and happiness,” he writes. What James wants us to understand is that the kind of “in flow” of surfing that involves an absorbed attunement to the world around oneself (i.e., killer waves and awesome tubes) is precisely the kind of flow and connection, what he calls here “adaptive attunement,” we need more of in our day-to-day lives.

What James has in mind is the everyday know-how that is not about thinking or cognition, but a theory of absorbed being-in-the-world activity that Martin Heidegger pioneered and the late University of California, Berkeley, philosopher and Heideggerian phenomenologist Hubert Dreyfus (What Computers Still Can’t Do; Skillful Coping; Background Practices, in addition to All Things Shining, et al.) later channeled, updated (in some crucial ways, even corrected) and took further. When all is going well in a state of flow, a carpenter doesn’t think about hammering; she just picks up the hammer and uses it. A driver doesn’t think about putting the key into the ignition or pushing the wheel here and there; she just does it. The tango dancer doesn’t think about putting this foot here or there; she just responds, in the whirligig rhythm of the song, by just doing and reacting, adaptively attuned to the partner, to every present moment and what follows next. The carpenter is absorbed into the hammering; the driver into the driving; the dancer into the dancing (and of course, the surfer into the surfing). When all is going well, there is no distinction between the dancer and the dance, the self and the world. She just is the dance. The “I” falls away. “The dancers don’t adapt to a changing dance space, but attune to each other in each new moment of the music, movement, or ensemble.”

Less and less of this kind of self-transcendent, connected, in-flow adaptive attunement to our world is possible these days, James wants to argue, and the disconnect between work life and leisure life is at the heart of the matter. “[W]ith all due respect for the 40-hour workweek, the key question for society is whether we have enough time to work for enough money and spend time with our family and exercise our skills at games or sports and serve our community and perform all the miscellaneous activities of adult life (for example, laundry, keeping the finances, cooking). Not to mention practicing the lost art of loafing. After you work to pay the bills, there’s not enough time left for the dedicated practice that gets you attuned to and enthralled by much of anything else.”

The whole notion of a surfer adaptively attuning herself to the comings and goings of the surf leads James to the inevitable question: What does it mean to adaptively attune to rising surf, as in the rising seas of climate change? To this, he follows through on a simple premise: The surfer’s contribution to climate action is to work less and surf more (i.e., overworking leads to a greater carbon footprint). It’s an idea that may seem too simplistic, even absurd on its face, but he backs it up with a discussion about the Basic Income Guarantee.

Throughout the book, James is in a constant dialogue with Jean-Paul Sartre, the French philosopher most famous for his existentialist manifesto Being and Nothingness. Yet it is perhaps Hubert Dreyfus with whom James seems to be talking most frequently here. Dreyfus’s many significant contributions to articulating Heidegger’s seminal work Being and Time, and especially, his critique of artificial intelligence, and analysis of everyday know-how and the cultural virtuoso (i.e., Aristotle’s phronemos), are crucial to James’s project—making Surfing with Sartre a wonderful application of Dreyfus’s work, and legacy.

What exactly is wrong with us these days? Simply put, we are too much in our own heads and cubicles. To this, James has a resounding answer: Work less, get out more, and get stoked.

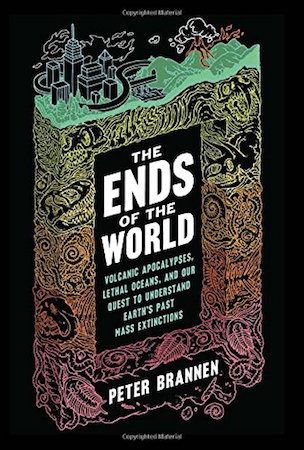

The Ends of the World

The Ends of the World

Volcanic Apocalypses, Lethal Oceans, and Our Quest to Understand Earth’s Past Mass Extinctions

Peter Brannen

Ecco, June 2017

—Heather Smith, news editor

When Farish Jenkins, co-discoverer of the world’s earliest known frog, was diagnosed with cancer, he told a visitor not to worry. “As a paleontologist,” Jenkins said, “I’m familiar with extinction.”

A similar attitude animates The Ends of the World by Peter Brannen, which takes an amiable journey through the surprisingly numerous mass die-offs in Earth’s history. The signs of these apocalypses can still be read in the rocks around us, and Brannen makes expeditions to numerous geologically significant sites, like the coastline of a former supercontinent behind a Boston-area Bed, Bath & Beyond, and a throng of Ordovician fossils frozen in permanent freak-out on the edge of a highway near Cincinnati.

Early on, Brannen hopefully asks Columbia University palaeontologist what the residents of future geologic eras are likely to think of Manhattan. He is gently rebuffed. “It’s not a sedimentary basin,” says Olsen.” It would erode away to nothing.” (Paleontologists of the future will, however, have a field day with New Orleans.)

Brannen doesn’t use the earth’s many prior atmospheres as an excuse to get complacent about our current one. As Lee Kump, head of geosciences at Penn State tells him, humans are pumping CO2 into the atmosphere at roughly 10 times the rate of the Endo-Permian, a time when volcanoes made much of the ocean as hot as a Jacuzzi and the land was too hot for even most insects to survive.

Your mileage may vary, but I found this book to be the perfect beach read. The world ends so many times that you shouldn’t expect an overarching storyline, but that also means it’s well-suited to dipping into and setting down again. Most importantly, the writing is vivid, funny, and a fine companion to a stiff, cool drink.

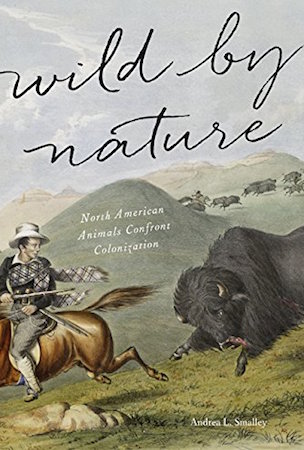

Wild By Nature

Wild By Nature

North American Animals Confront Colonization

By Andrea L. Smalley

Johns Hopkins, May 2017

—Paul Rauber, senior editor

Early European explorers in the New World were gobsmacked by the profusion of wildlife. “The magnificent God,” wrote Edward Haies in 1583, had “superabundantly replenished the earth with creature serving for the use of man.” Deer were already scarce in his native England, and poaching a hanging offense, but in America a European with a gun was like Shiva the Destroyer. Andrea Smalley, a meticulous researcher, cites Thomas Walker, who surveyed Kentucky in 1749 and whose party killed “13 Buffaloes, 8 Elks, 53 Bears, 20 Deer, 4 Wild Geese, about 150 Turkeys, besides small Game.”

Early boosters of colonial expansion touted this bounty to lure settlers. “‘Even the timid need not delay,’ one tract insisted, since wild animals such as bears and wolves were entirely shy and harmless,” and early colonists in New England imagined that moose might be tamed to the yoke. Smalley explores how America’s wild fauna challenged colonialism (wolves, for example, running free and sabotaging notions of staid, English-style pastoralism). But they also abetted it. In Smalley's saddest example, the Plains Indians' connection to the buffalo was used to delegitimize their land claims, and extirpation of North America's iconic beast became a military tactic to grease Manifest Destiny. Writing in 1844, George Catlin, famous painter of Native American subjects, made genocide seem romantic: “[T]he Indian and the buffalo—joint and original tenants of the soil . . . have fled to the great plains of the West, under an equal doom . . . where their race will expire, and their bones will bleach together.” The animal of which this wise volume will most change your impression is the human one.

Enigma of the Owl

Enigma of the Owl

An Illustrated Natural History

By Mike Unwin and David Tipling

Yale University Press, February 2017

—Sam Murphy, photo editor

Arguably, owls, out of all the birds, are the easiest to anthropomorphize. Yes, other birds are beautiful, striking, and wondrous, but one tends to admire their plumage like a flower, especially in the medium of photography. The Enigma of the Owl conveys the character and diversity of owls through photographs and shear sweat-equity. In the tradition of beautiful, hefty coffee-table books, David Tipling tries to capture the length and breadth of this mostly nocturnal creature. He has 53 species documented in the 280-page book. The imagery’s quality allows the viewer to see simultaneously a grace and silliness of an individual bird, not just the expected wide-eyed “wise” animal. Readers find themselves giggling at the bird’s personality and predicament while entranced by its physical details. Every photo is complex. Through concise captions at the header providing informative statistics, including the owl’s ranking for endangerment, people of all ages can gain something through a lighter thumbing-through. Conservation photography attempts to create a deeper connection between the modern human and nature. This book, through its high production value, succeeds in that endeavor. The Enigma of the Owl is a great visual reference book for families and artists.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club