Can Tribes and Tigers Coexist in India's Nature Reserves?

Sierra's correspondent visits the Soligas and the Chenchus to find out

Thokala Ravi, Balamur Lakshmaiah, and Nimalla Balaguruvaiah on patrol in the Amrabad Tiger Reserve, India.

THE TIGER WAS BRIGHT RED with wavy black stripes. Its unblinking, almond-shaped eyes gazed straight ahead, its mouth open in a frozen grin. Colorful flower garlands cascaded down its back and around its neck, a floral wreath rested delicately atop its head, and bananas were wedged between its teeth. Coconuts and fruits were spread before it.

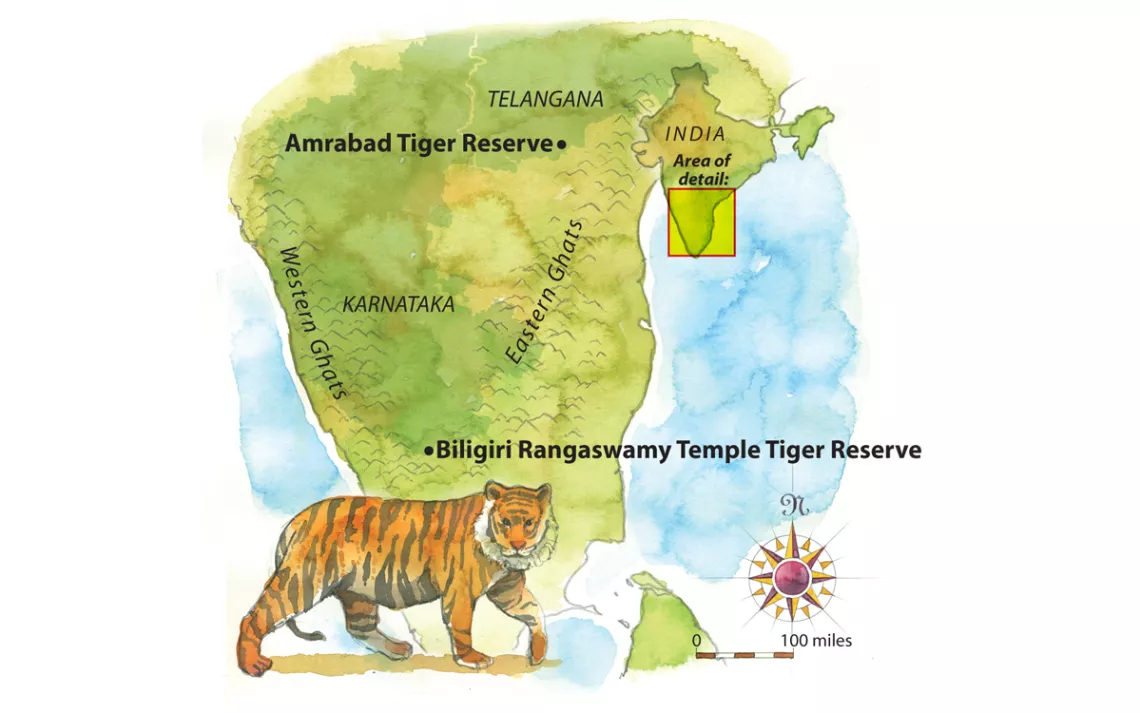

I was in the Biligiri Rangaswamy Hills (also called the Biligiri Rangana Hills, or the BR Hills) in southern India, where the Soliga tribespeople in the village of Muthagada gadde Podu were venerating a new wooden tiger idol associated with the god Shiva. These hills run through the state of Karnataka and link the mountains of the Western Ghats to those of the Eastern Ghats, forming an important corridor in which species from each range mingle. Just over 200 square miles of this unique environment are protected as the Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple (BRT) Tiger Reserve. It is part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, which includes the more famous Bandipur and Nagarhole tiger reserves, and is one of the most tiger-rich regions in a tiger-poor world.

Madamaa, a Soliga elder in India

The rapid rhythm of drums lent an air of urgency to the ceremony. A shirtless priest purportedly possessed by Lord Shiva struck himself with steel weapons to prove his divine strength. He blessed the surrounding crowd, then criticized the color of the tiger statue as unrealistic. After waking from the trance, the priest led the procession to a temple several villages away. A team of men carried the statue on their shoulders like royalty.

The new idol represented Huli Veerappa, a tiger sacred to the forest-dwelling Soligas. An avatar of Shiva is said to have ridden the tiger through the Biligiri Rangaswamy Hills, where the tribe has lived for centuries. They believe that offerings to Huli Veerappa at festivals like this one help protect them from misfortune. But when it comes to actual tigers, the Soligas see themselves as the protectors. They live inside the BRT Tiger Reserve, in close proximity to the tigers that roam there.

The idea that tribal communities can coexist with, and even help protect, tigers and other threatened species that inhabit their ancestral lands is a contentious one in India. I had come to the BR Hills for a firsthand look at how the Soligas may be helping, or hurting, India's tiger-conservation efforts.

ONLY A CENTURY AGO, an estimated 100,000 tigers prowled the planet—some 40,000 in India alone. Then intense hunting and habitat loss devastated tiger populations, and by 1970, fewer than 5,000 remained worldwide. In India, fewer than 2,000 survived.

With the tiger on the verge of extinction, India passed the Wildlife Protection Act in 1972. The following year, it launched Project Tiger, a campaign to save its newly declared national animal. Over the next several decades, India's wildlife-sanctuary system rapidly expanded from just 10 national parks to more than 100; there are now over 600 protected areas in the country, including 50 tiger reserves.

But this massive effort to save the tiger and other endangered species came at a huge cost to tribal communities living within the boundaries of the newly established wildlife preserves. Following widely accepted conservation orthodoxy, India began evicting the people who lived in protected areas; thus far, more than a million people have been forced to resettle elsewhere or prohibited from living off the land, often with catastrophic human and cultural consequences.

Soliga tribal leader Achugegowda

By the early 2000s, a small but growing group of international conservationists had begun rethinking the wisdom of removing indigenous groups from their ancestral lands. In India, protests against the displacement of tribal people gained traction, eventually resulting in the passage of the Forest Rights Act in 2006. The FRA guarantees the rights of "traditional forest dwellers" to live on and use the lands they've relied upon for generations, even within national parks. At about the same time, the Tiger Amendment was added to the Wildlife Protection Act, granting people living in tiger reserves more protections from eviction.

But with forest departments run by state governments rather than a central authority, implementation of the FRA and the Tiger Amendment has been scattershot. In many cases, tribes' rights exist in a gray area, in which park authorities seem to adopt policies at their own discretion, rarely following the letter of the law.

When a wildlife sanctuary was established in the BR Hills in 1974, the Karnataka Forest Department pressed the Soligas to settle in one centralized area near an important hilltop temple dedicated to Biligiri Rangaswamy, an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu. Many of the Soligas eventually, if reluctantly, complied. In Muthagada gadde Podu and surrounding villages, I spoke with tribal elders who remembered spending their early years deep in the forest and recalled watching officials use trained elephants to crush their families' huts and fields, leaving them little choice but to relocate.

Before resettlement, the Soligas had lived in small groups scattered throughout the forest. They practiced shifting cultivation—burning undergrowth, planting fields, then moving to a new location to repeat the process. They also gathered tubers, honey, and amla (Indian gooseberry) and hunted deer and smaller animals.

Most Soligas now reside in small hamlets not far from the temple, surrounded by the core area of the BRT Tiger Reserve. They live in spartan cement homes provided by the government or a local NGO. Some Soligas have chosen to remain in the wilderness, but they must stay in permanent settlements. Shifting cultivation is prohibited, and most Soligas no longer grow much food for themselves, opting to harvest coffee instead, which they sell for cash. The forest, however, remains a vital resource for most families, who rely on the collection and sale of honey, medicinal plants, and other non-timber products to eke out a living. (Hunting has been banned for over 40 years.)

The forest also continues to be an essential part of the Soligas' cultural and spiritual identity. While in the BR Hills, I met Dr. C. Madegowda, a Soliga leader who works for the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), which runs the small guesthouse where I stayed. Easygoing yet perpetually busy, Madegowda is one of very few Soligas with an advanced degree. After warning me against leaving the grounds at night to avoid being trampled by elephants (I'd already been advised to close my windows to keep out the cobras), he showed me a map of 489 sacred Soliga sites in the BR Hills, many of which are rocks, trees, or springs. Some represent deities; others embody the spirits of ancestors. "Everything in nature has a soul," he said. "The forest is our god. . . . We worship the trees and animals." Among these deities is the tiger.

"Tigers are holy animals. We never kill them. We sing about them. We protect them," Achugegowda, a Soliga leader with snow-white hair, told me as we sat under a shady tree outside his home in the village of Yarakana gadde Podu. He explained that his people have always lived side by side with tigers, without conflict. "We know how they behave—and they know how we behave—so we avoid problems. We've observed everything about them, even their facial expressions and the ways they hold their ears. . . . When we see one in the forest, we speak to it and call it a big dog. If we called it a tiger, it would feel very powerful, but when we call it a dog, it feels small and moves away from us."

Another tribal leader, Karanakethegowda, who had organized the ceremony for the new tiger idol, spoke more bluntly. "Who killed the tigers? City people! We have always protected the forest, but only for the past 30 or 40 years has the government been interested in saving tigers."

Map by Steve Stankiewicz

Dr. Nitin Rai, a political ecologist with ATREE, believes that the very presence of Soligas in the forest has helped keep tigers safe. Since the Soligas are frequently out collecting wild edibles and herbs, or grazing small herds of goats, "they know everything that's happening in the forest, which deters poaching," he said. This matters, because while tiger numbers are on the rise in India, tiger poaching is a major concern. At least 50 were poached nationwide in 2016—twice as many as in 2015—feeding a multimillion-dollar market in tiger-based Chinese medicines and luxury products. But tiger poaching is virtually nonexistent in the BRT Tiger Reserve.

At least some of the Karnataka Forest Department officials seem to have warmed to the notion that the Soligas have a role to play in protecting the reserve's tigers. M. Nagajaru, the assistant conservator of forests in charge of the BR Hills, told me that the forest department employs some of them as "tiger watchers," who live in anti-poaching camps and patrol the forests on foot every day, keeping tabs on human activity and wildlife. The patrols are equipped with GPS-enabled smartphones. If a watcher sees a tiger, leopard, bear, or any other animal, he presses the screen icon for that species, and the time and location are uploaded directly to a forest department database.

In 2011, the Soligas became the first tribe in India to have their rights to live in and use the forests within the core area of a tiger reserve legally upheld under the Forest Rights Act. Since around that time, according to the most recent census, tiger numbers in the BRT Tiger Reserve have nearly doubled—increasing from 35 to 68—lending some weight to claims that the tribe's presence is helping tigers rebound, or at least isn't hurting them. But is this the exception or the rule for tiger conservation in India? I wanted to know whether other reserves where tigers and tribespeople live in close proximity were experiencing similar success.

THE AMRABAD TIGER RESERVE LIES 300 miles northeast of the BR Hills, in the state of Telangana. I had been invited to stay with the family of Thokala Guruvaiah, a tribal leader of the Chenchus. He and his family live about an hour outside the park entry gate, in a remote settlement of bamboo huts with grass roofs topped by small solar panels. Upon arriving, I was greeted with happy news: We'd have meat for dinner. That morning, a leopard had killed a deer nearby, and the family had scavenged the leftovers.

Soliga tribesmen preparing a new statue of the tiger god Huli Veerappa

For centuries, perhaps millennia, the hilly wilderness of the Nallamala Forest has been home to the Chenchus. After the passage of the Wildlife Protection Act, some Chenchu villages were forced to resettle, but the eviction process was slowed by a variety of factors, including the nearby presence of armed Maoists, which hampered law enforcement. Today, some 10,000 Chenchus live in a core area of more than 2,000 square miles within Amrabad and the adjacent Nagarjunsagar-Srisailam Tiger Reserve.

Guruvaiah's 21-year-old son, Leela—who spoke fluent English that he'd learned from American movies and YouTube videos while attending a government-run boarding school—had arranged for me to join a tiger-tracking patrol employed by the Telangana Forest Department. Having once been a tracker himself, he explained that crews of two to four men cover six to 12 miles each day. They record everything they see and hear, from tiger sightings to leopard calls to fresh porcupine scat.

Leela and I set out with three trackers early in the morning, walking beneath leafy canopies and over hills with yellow, waist-high grasses. One of the trackers carried a bow and a handful of arrows, some blunt-tipped, others dagger-sharp. "We use them for protection from bears," explained Nimalla Balaguruvaiah, the senior member of the team, with 15 years of experience tracking tigers. "They're the only animals that are really aggressive."

We came upon a clearing about the size of a baseball field, where all that remained of a seasonal pond was a dried mudflat and a few dirty puddles. A family of spotted deer looked up, paused, then bounded off into the trees. The trackers scanned the soft mud around the water holes for tiger pugmarks but found none, so we continued on. We followed no discernible trail, stepping over fallen branches and around large ferns and man-size anthills that looked like they had been hewn from sandstone. During the nearly three-hour trek, we saw boars, eagles, and more deer, plus the remnants of kills left by wild dogs and a leopard, but no tigers.

"This forest is our home. We know everything in it," Balaguruvaiah told me later. "If there were no tiger trackers, poachers would come here and lay traps, kill tigers, and sell their skins and body parts on the black market. Smugglers would cut all of the valuable wood, and the forest would be destroyed."

A camera trap captures a tiger at Bandhavgarh National Park, India | Photo by Steve Winter/National Geographic Creative

In his family's hut, tribal leader Guruvaiah expanded on this. "We even keep an eye on the forest department," he said. Without the Chenchus, he argued, park officials could sit in their offices all day and never come into the field, or could accept bribes to look the other way when smugglers went into the forest. What's more, the government recently approved testing for uranium deposits within Amrabad, and the Chenchus promise to protest if plans to mine the radioactive ore move forward. "Without us, no one would fight it," Guruvaiah said.

"They are the eyes and ears of the forest," said Balu Palipaka, the Telangana editor for the Times of India, who has reported on the area since the 1980s and whom I met inside the park. "Nothing happens here that they don't know about."

Unlike in the BRT Tiger Reserve, the tiger population in Amrabad—estimated to be in the mid-teens—has remained relatively flat over the past decade, failing to match the gains made in other parks. Both the local forest department and the Chenchus blame this on the naturally dry landscape, which lacks the water to support a larger population of big cats.

Nevertheless, the increasing tiger population in the BR Hills and in a few other reserves has convinced some environmental researchers that tigers and people can coexist, a conclusion that human rights groups are eager to embrace. "The fact that tiger numbers are going up in the BRT Tiger Reserve at a much faster rate than elsewhere in India shows that evicting tribal people from tiger reserves is counterproductive for tiger conservation," tribal advocate Sophie Grig, of Survival International, wrote in an email.

OTHER CONSERVATIONISTS, however, maintain that the only real hope for saving India's tigers is to keep people out of the less than 5 percent of land that has been set aside for wildlife habitat.

I asked the director of the Wildlife Conservation Society's India Program, Dr. Ullas Karanth—a prominent tiger researcher who has spent decades working in Karnataka—what the case of the BR Hills says about people and tigers living together. "It says nothing," he replied. "In the early 1970s, these forests were trashed and tigers were almost extinct. . . . Their rebound is entirely because of regulations. . . . Enforcement [of wildlife laws] is what has brought prey species and tigers back" to the BR Hills. He also rejects the touted doubling of the tiger population in the BRT Tiger Reserve since 2010, asserting that there's a lack of rigorous data behind the numbers.

The average male Bengal tiger (the subspecies found in India) weighs around 480 pounds and eats about one cow-size animal a week. How much territory it needs depends on the density of prey. Each breeding female requires up to about 40 square miles, and male tigers occupy the range of three to four females. "You cannot have people also raising cattle, doing agriculture, and hunting the prey species in those habitats," Karanth said. "It doesn't work."

He went on to say, "I don't think there is a single family in India that does not want electricity, clean drinking water, a decent house, a bus to come and pick up their kids to take them to a nearby school. So the question is how do you deliver that to 1.2 billion people while keeping at least the remaining fragments of nature intact?" While the process of relocating forest dwellers should be "humane and fair . . . so people are truly better off afterward," the solution, according to Karanth, is to take people to where services already exist rather than bring services to remote locations in the forest and destroy the country's last remaining natural areas.

Conservationists who share Karanth's view and those who believe that forest dwellers can coexist with tigers agree on one point: Banning hunting has been the most important factor in the resurgence of wildlife in India's protected areas. Otherwise, the two sides share little common ground, and each questions the other's data, interpretations, and motives.

For now, debate over the meaning of the growing tiger population in the BRT Tiger Reserve may be beside the point for two reasons: The park has nearly reached its maximum tiger density (according to the forest department), and the Soligas aren't leaving anytime soon. In fact, they are eager to play a bigger role in official conservation efforts.

At the ATREE office, Madegowda showed me a joint management plan that he helped create. It lays out how the operation and oversight of the BRT Tiger Reserve could be shared between the government and the tribe. Such an arrangement, Madegowda said, would go a long way toward preserving both Soliga culture and wildlife habitat in the BR Hills, and could be a model for tiger reserves around the country, especially in parks such as Amrabad, where forest dwellers like the Chenchus are already involved in conservation efforts.

So far, he said, the forest department has shown no interest in the plan.

"Right now . . . no one making decisions is asking the community about our knowledge of the forest," Madegowda said. "If Soligas partner with the government, we can offer input based on our deep understanding of the ecosystem. We are open to recommendations about how to improve the way we do things, to reduce our own impact. If we all share our knowledge and manage the forest together, we can protect it better. This is the best way forward for everyone, including the tigers."

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's International Tiger Protection Project.

This article appeared in the July/August 2017 edition with the headline, "The Tiger Watchers."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club