Across the U.S., Rivers Are Running Free After Decades of Impoundment

A writer paddles the length of the Rogue River after dam decommissioning

Rafting on the Rogue River in Oregon | Photo by Dan Arnold

A RIVER IS SOME SPOOKY MAGIC. Apparently out of nowhere, water rises from solid earth and falls toward a distant sea. The water flows ceaselessly, never running dry, because another, parallel river passes through the sky. The massive force of water rubbing by every inch of riverbank each second—enough weight to carve the Grand Canyon and slice the Columbia River Gorge—is lifted out of the ocean by the sun and floated back into the mountains through the air. It is such a fantastical cycle that no one would believe it if it weren't ordinary.

The Rogue River, in southwestern Oregon, embodies this liquid alchemy. The Rogue begins by bursting through the brown volcanic bones of the side of Mt. Mazama, eight miles from Crater Lake, and then twists and turns for 215 miles until it pours itself into the Pacific Ocean. At the start, it is no crick or seep but already a full-bodied river, having gathered its waters from a thousand underground capillaries in the mountainside, leaping from stone into sunlight like Athena emerging full-grown from the knobby old skull of her father.

I stood on dry ground, toes pointed downstream, mesmerized by the sight of the water sliding out of the earth. Traveling the mountains, I've tasted some fine waters, but nothing as sweet as the Rogue at its headwaters. I'd come here to get the whole river in my head, to start at the very beginning and end at the end. On my back, I had food for a week, my sleeping bag and pad, my bivy sack, and my pack raft, paddle, and wetsuit. Like the river, I'd stop when I got to the ocean.

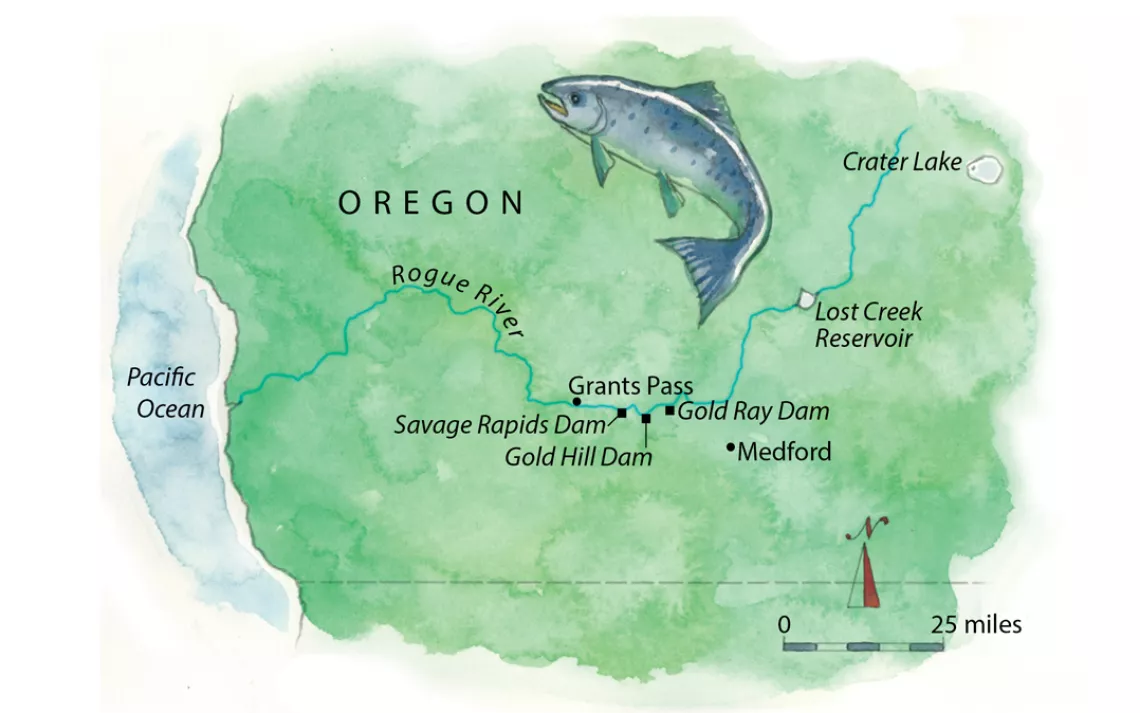

When Congress passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968, sections of just eight rivers were included. That exclusive list included the lower Rogue, an 84-mile stretch of remote canyon, whitewater, and deep forest beginning at the Rogue's confluence with the Applegate River and ending near the Pacific. In 1988, Congress extended wild and scenic status to 40 miles of the upper river. American rivers tend to rise clean from the mountains and transform into glorified canals by the time they reach the sea. By contrast, white settlers industrialized the Rogue's middle stretch, watering (and sewering) the cities and agricultural enterprises of the Rogue Valley. A river that for millennia swarmed with salmon runs thick enough to support a beaded string of Native American tribes was interrupted by a chain of dams and reservoirs built to control flooding, irrigate fields, and generate electricity.

Now the Rogue is a laboratory for dam removal. In the past decade, three dams on the main stem of the Rogue—Gold Ray, Gold Hill, and Savage Rapids—have been torn down. Four sizable dams on tributary branches have also been removed, as well as many other manmade obstacles to fish passage. Restoration ecologists have replanted the riverbanks with willows, sedges, and other native plants. Salmon and steelhead are arriving at their spawning grounds weeks faster than before and reaching tributary beds they haven't populated in decades. Every year, more miles of previously fragmented waterways are reconnected to the river system.

The restoration of the Rogue is part of a broader trend: Across the United States, government agencies and private groups are demolishing ill-conceived or obsolete dams. In Olympic National Park, the steel-gray waters of the Elwha River now crash past the hulking ghosts of two former dams, removed in 2011 and 2014, restoring a vital salmon run. In New England, the Penobscot is again flowing free to the sea. In California, the San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River is no more. Other dam removals are in the works. California, Oregon, and the utility company PacifiCorp have agreed to tear down four major dams on the Klamath River; once the deal is finalized, the removal of those dams will constitute the largest river restoration in U.S. history. According to American Rivers, more than a thousand dams have been removed in the United States in the last 30 years. Each time a dam disappears, scientists learn more about how river systems recover, and local environmental groups calibrate the legal levers that bring dams down.

I LAUNCHED JUST BELOW Muir Creek, after a 10-mile hike through the burn zone of the 2015 National Fire, which left me grimy as a chimney sweep. As I paddled, the river twisted through playful curves and riffles. The water was so clear, I could have been flying rather than floating; the gravel beds 10 feet below my tubes looked close enough to touch. The river swung through big bends at the bottom of a deep canyon. The stone was pure Mazama pumice, much too soft to be held vertical for long, and a gentle rain of rock poured off the cliffs. Pumice floats, so fist-size stones bobbed alongside me in the current. Where bedrock surfaced, the water turned white and roared.

Three days later, the river stopped. The water turned brown and bloated with algae. Rotting old snags poked through the stagnant surface from below. I bumped the bow of my boat against the buoy chain guarding the intake of the North Fork Reservoir dam—one of the two remaining dams on the main stem—then paddled to shore. Each day so far, the Rogue had seemed to double or triple between morning and night. Now, below the diversion dam, I walked on water-carved basalt pavement next to a much-diminished river. The sun was on the decline and so was I when I heard and then saw the PacifiCorp powerhouse.

I launched again and floated while the generators cranked out some 30 megawatts. The vibration of the machine, or maybe just the churn of the water, shook the air. Swollen back to its right size, the river turned into a long, turbulent boulder garden, then died another death in the massive Lost Creek reservoir. I paddled four miles of flat water, feeling restless and unwilling to stop, reaching the Highway 62 bridge as evening settled. Water-skiers roared by. A pontoon barge stopped, and I was handed a Coors the size of a Pringles can. It had been a long, strange day. I'd woken on the banks of a truly wild, snowmelt-fed river, run the last of its rapids, and ended up floating on an engineered tank, listening to Aerosmith and Snoop Dogg.

The next morning, I paddled to the William L. Jess Dam, past rental houseboats festooned with floaty toys. At the dam, I walked a long pier, chatting up the fishermen. One fellow wasn't fishing. At the end of the pier, Bob Hunter was watching birds through an enormous pair of binoculars.

In pro-dam editorials that occasionally appear in local papers, Hunter shows up as a kind of evil specter orchestrating the Rogue dam removals. In reality, Hunter is slight, soft-spoken, and gray-bearded. He's a retired lawyer and old-school fly fisherman living on a 12-acre farm in the Rogue Valley. But don't be fooled. Craig Harper, a longtime colleague, describes Hunter as a bulldog. "He doesn't pound the table," Harper told me. "He doesn't yell. But once he gets ahold, he doesn't let go."

A few months before our meeting on the pier, Hunter took me on the grand tour of dams he had helped to demolish. It began with Savage Rapids, just upriver of Grants Pass, a river-wide concrete diversion dam providing no electricity or flood control and wasting more water than it delivered to area farms. It was "the most notorious fish killer on the Rogue," Hunter said. In the mid-1980s, a time when ocean conditions produced the largest salmon runs in memory and the dam carnage was at its worst, Hunter dreamed up a plan with Tom Simmons to uproot Savage Rapids.

Simmons, cofounder of WaterWatch, for which Hunter worked from 1985 to 2015, had identified a trigger to take down the dam. The operator of the dam, the Grants Pass Irrigation District, used only a fraction of its water right while wasting the rest. During recertification with the state of Oregon, the irrigation district was required to apply for more water, and WaterWatch stepped in to file a protest in 1988. Twenty-one years later, after a river's worth of legal and political twists and turns, the dam was gone.

The victory changed the thinking in the Rogue watershed from dam rehabilitation to dam removal. It set the precedent for the projects that followed and provided river advocates with a strategic blueprint. Hunter repeatedly stressed the need for using legal wedges to remove problem dams. "Without some kind of legal handle," he told me, "you have no leverage in negotiations."

When opportunities emerged to remove the Gold Hill and Gold Ray Dams, the network of now-experienced river advocates that had cohered around the Savage Rapids project responded quickly. Both Gold Ray and Gold Hill were long obsolete—Gold Ray, for example, was built in 1904 as a timber-crib diversion dam to power a nearby gold-mining operation and was replaced with concrete in 1941. It hadn't produced a watt of electricity since the 1970s. But it spanned the river and killed fish, and 400,000 cubic yards of silt clogged its reservoir. The dams had become expensive liabilities for the local governments that had inherited them. Gus Wolf, a former mayor of the town of Gold Hill, said that in 1964 the local power company had essentially "dumped [the dam] on us." The Gold Hill Dam came with PCBs in its power station, which the city had to clean up.

Old dams persist in part because they are expensive to remove and in part because history dies hard. At local hearings, pro-dam protesters jammed county government meeting rooms. A nostalgia was at work: The dam-removal projects took away not just concrete but, for some, a sense of heritage.

But history goes back much further than the last century. At one point, as giant excavators and jackhammers munched apart the concrete structure of the Gold Ray Dam, the project's supervisor, John Vial, looked in the water below and saw 30 large Chinook salmon gathered there. Vial remembers that it was as if they were saying, "Hey, can you hurry that up? We've got places to go."

Vial's pride in the project is obvious. "If you visit now, you'd never know the dam was there," he said. "The restoration was complete."

Now Hunter gave me a ride to the outflow below the William L. Jess Dam and released me back into the river like a fish, knowing that I'd float another 157 miles to the sea without crossing another dam, thanks in large part to him. The practical effect of Hunter's work is a river full of water and salmon. His larger accomplishment is helping to redirect the Rogue's future—and rewrite the history of rivers across the West. Dam by demolished dam, Hunter is creating a new aesthetic, centered on a living watershed.

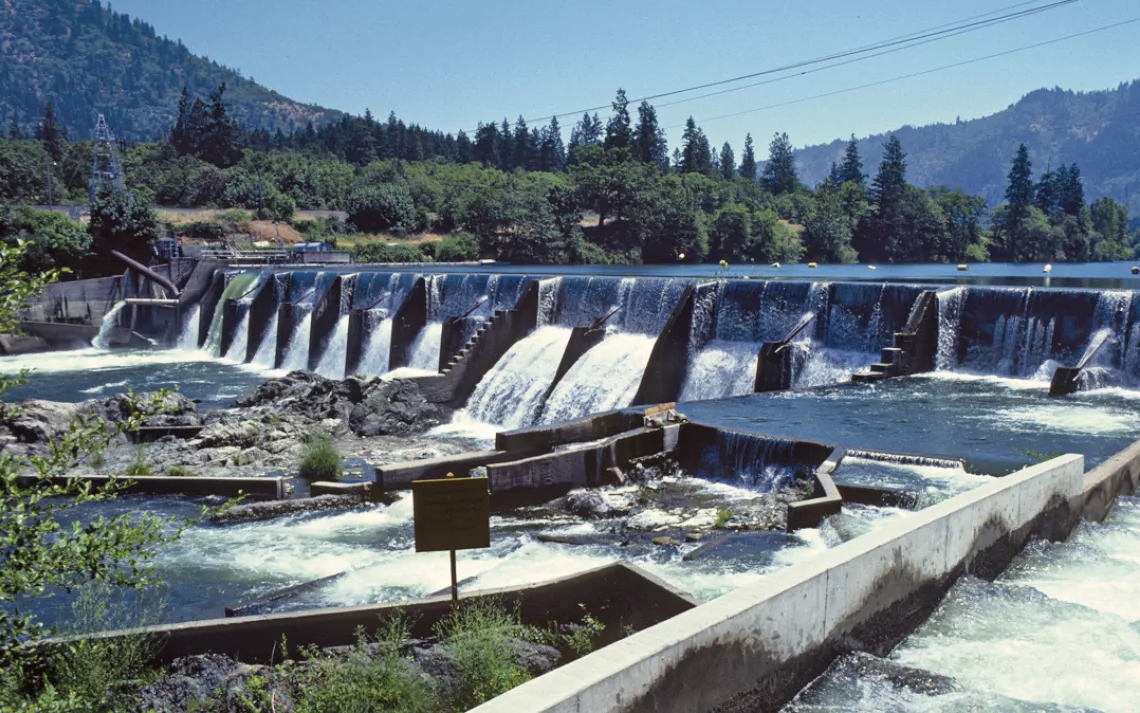

The Savage River Dam site in 1979, before being dismantled | Photo courtesy of Glade Walker/US Bureau of Reclamation

The Savage River Dam site in 2010 while being demolished | Photo courtesy of Scott Wright/River Design Group

The Rogue River restored after demolition of the Savage River Dam in Oregon | Photo by Dan Arnold

I HAD RETURNED TO a populated river. The Rogue is the soul of southern Oregon, and just about everyone seems to own a boat and gravitate to the river for one reason or another. Every variation of aluminum fishing boat and inflatable kayak and raft rode the current. Houses lined the banks, mostly modest homes with funky docks and fishing piers, but also complicated mansions of wood and stone and glass, with lawns reaching to the water's edge.

The next day, I paddled past the outflow of Little Butte Creek. Up the creek a short distance the previous spring, I'd met Jay Doino, a fish biologist for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and Eugene Wier, the restoration project manager at the Freshwater Trust. While I squelched along in running shoes, Doino and Wier, equipped with hip waders, planted willow cuttings. Doino said that when he'd started restoring Little Butte Creek in 2008, nothing but a barren, straightened channel left over from an old gravel mine had flowed into the Rogue. In its place, I saw a sinuous, 80-foot-wide channel lined with trees and marsh grass. By replanting willows and strategically placing logs, Doino and Wier and their crews were coaxing the waterway back into something like its natural shape, transforming a postindustrial canal into a living tributary.

Tributaries matter. A river is nothing but the sum of its feeder creeks. Tributaries cleared of streamside vegetation heat up; tributaries full of agricultural runoff carry their nutrient load to the river. When the spring floods come through, channelized tributaries simply dump water straight into the river. With its curves restored, Little Butte Creek now broadcasts water in all directions, creating marshes and pools, holding the water on the land.

Salmon and steelhead require cold water, and the Rogue's food web depends on the fish, which means that global warming will eventually unravel this ecosystem. "Our job," Wier told me, "is to shepherd those cold source waters down from the headwaters through the basin, keeping it as cold and clear as possible." One of the preferred methods is to revegetate stream banks with native trees and plants, providing living thermal shading. The work requires a long-term vision. Wier told me that the Freshwater Trust won't touch a project that doesn't look at least five years down the line.

Illustration by Steve Stankiewicz

At the edge of one pool, Doino told me to stop. He pointed out some inch-long fish congregated around a submerged log. "Those are Chinook," he said. What I'd taken to be a puddle was actually a part of the whole river system. "That's connectivity," he told me. "The fewer barriers the better."

Now, six miles downriver from Little Butte Creek, I paddled by the former Gold Ray Dam site. John Vial has every right to be proud: Six years after the dam's removal, one could float past without knowing it once stood there. A day later, I arrived at Savage Rapids. It's a more industrial site, with a remnant buttress of the former dam and a new, more efficient pumping station for the Grants Pass Irrigation District—part of the compromise crafted by WaterWatch. Eight years of regrowth had turned the reemerged riverbanks electric green. The concrete bones of the old dam didn't seem so bad, a reminder of the past and a caution against hubris.

I talked to Desiree Tullos, an associate professor of water resources engineering at Oregon State University, about the speed of recovery on the river. She studied the Rogue before and after the removal of Savage Rapids Dam, and her research shows that the changes happen fast and go beyond passing visuals. Prior to the dam removal, blackflies, midges, and chironomids—species indicating a low-oxygen, high-silt environment—dominated the waters around the dam. One year after the removal of Savage Rapids, mayflies, stone flies, and caddis flies—species that are emblematic of clean rivers and provide food for salmon and steelhead—had returned. At the former site of the Gold Ray Dam, Doino had observed salmon redds in the reservoir pool within one month of the dam deconstruction. After the removal of the three main stem dams, fish now reach the William L. Jess Dam earlier than before.

Tullos found that for the Savage Rapids area, the ecological recovery (indicated by the balance of macroinvertebrate populations) took a single year. The geomorphic recovery (changes in the material makeup of the riverbed) took three years. We talked about other dam-removal projects across the country, and the predictive specificity she could apply to river-recovery scenarios blew me away. "So there's a whole developing art of dam removal," I said. "No," she corrected me, "it's a science."

I asked if her team was continuing research on the Rogue. She told me it wasn't needed. The river had recovered.

THE NEXT MORNING, I paddled into Grants Pass, where the river runs right through the city. I assumed the river-city interface would be ugly. I couldn't have been more wrong. Bedrock cobblestone cliffs draped with flowers and hanging vines channeled the river. I saw seven beavers on the way into the city, one practically in downtown.

On the other side of Grants Pass, I descended deep into river time. Hours slipped by in minutes, and minutes ballooned into hours. I paddled through long, forgotten bends and down famous whitewater. I was enclosed by deep woods and canyon walls, and the outside world turned unreal.

Storm clouds massed and split open. I paddled hard to stay warm and make miles—just me and the river and the rain. The canyon broadened, and the river swung through wide loops by rock-strewn beaches. Clouds wreathed dark-green hills. Osprey mined the water for fish. Even washed by the rain, I could feel the marine air rolling in from the coast. I stopped on a beach and found blackberries near as big as my thumb. They tasted like concentrated sunshine.

The clouds bunched back up into floating mushrooms. I wasn't going to make it to the ocean this day. A broad curtain of rain hung in the west. Under a willow thicket, I crawled into my bivy sack, which leaked all night long.

The following morning, the river carried me out to the Pacific, past cormorants and harbor seals and fishing boats. The water turned from fresh to salt, from current to waves. The river finished one more turn of its infinite loop and dropped me into the sea.

This article appeared in the May/June 2017 edition with the headline "Free at Last."

MORE ONLINE

WATCH Daniel Arnold as he paddles the Rogue River.

READ about how a creative coalition saved Illinois's Allerton Park from an ill-conceieved dam.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club