Mexican Fisherman Juan Castro Saved His Beautiful Marine Ecosystem, and He'll Save Yours, Too

A diving epiphany leads to an explosion of marine life and new prosperity for a Baja California village

Juan Castro Montaño | Photo by Octavio Aburto

The sea 40 years ago was calm and clear. It had what Juan Castro Montaño calls espejismo, which translates somewhere between mirror and mirage. It was a scorching summer day in the late 1970s, and Juan, a subsistence fisherman from a dusty village in southern Baja, Mexico, leapt into the glassy waters of the Sea of Cortez and had an epiphany that may change marine conservation forever.

From the age of 12, Juan earned his living from the sea. His childhood was spent not in classrooms but in boats, working hooks and lines that he’d pull from the water with small, calloused hands. He grew up in Cabo Pulmo, a tiny village tucked between beige mountains and a green sea. A trickle of tourists would wander down its dirt road; sometimes they would pay Juan to take them fishing. But on the day of Juan’s epiphany, his customers only wanted to see the reef.

The heat was brutal. The tourists dove into the sea with their diving equipment, leaving Juan in his boat to bake in the sun. Between the bags left behind, Juan spotted an extra mask. Thinking only of escaping the heat, he strapped on the mask and threw himself over the side of the boat and into the water.

As the bubbles subsided, he saw below him the black silhouettes of six divers and a garden of coral so beautiful, he says, that it looked like it was “tended by the hand of God.” It was the first time Juan had seen the reef. He was overwhelmed at the beauty of the corals, but his joy vanished the moment he saw the long scars, the crushed structures like buildings demolished in a war zone, and the lack of marine life around them.

Why such destruction? Juan lifted his head above the water and looked to land. Tracing the rounded contours of the mountains on shore with his eyes, he saw that they were the same formations he had used for decades to find his fishing grounds. It was here that he would throw his anchors. "I was part of this destruction," he thought.

He floated for a while, lost in sadness. But then, like a fire from his gut came a single thought: I’ve got to do something.

And within 24 hours, he had.

♦

Juan is 71 years old now. I meet him at his family’s restaurant, which flanks the beach at Cabo Pulmo. The restaurant is closed for the day; Juan is sitting on a plastic chair, gazing out to sea. He’s mostly bald, the remaining hair that frames his ears a brilliant white. It matches his mustache.

At first, Juan is guarded, but we end up talking for hours. I pick a time period, and he describes it with incredible detail, triangulating the dates from important soccer matches or a summer solstice or the visit from the prince of Holland. He even has stories from before he was born. “Those are the stories of my father,” he says.

Juan tells me of a time when only five families lived in Cabo Pulmo, and the fishermen hunted packs of sharks; shark livers sold at a premium, especially during World War II. (Juan still has the jaws of a great white in his house.) He tells the story of his life, from a child learning from his dad on the sea, to the time he worked as a boat captain for Jacques Cousteau. He talks about the commercialization of fishing, of the boats that trawled the depths while he kept line fishing by hand in his tiny boat. His whole family fished: his brothers and cousins and nephews and sons. He loved his profession. The sea, Juan says, gave him food, gave him pleasure. But then, the sea ran out of fish to give.

♦

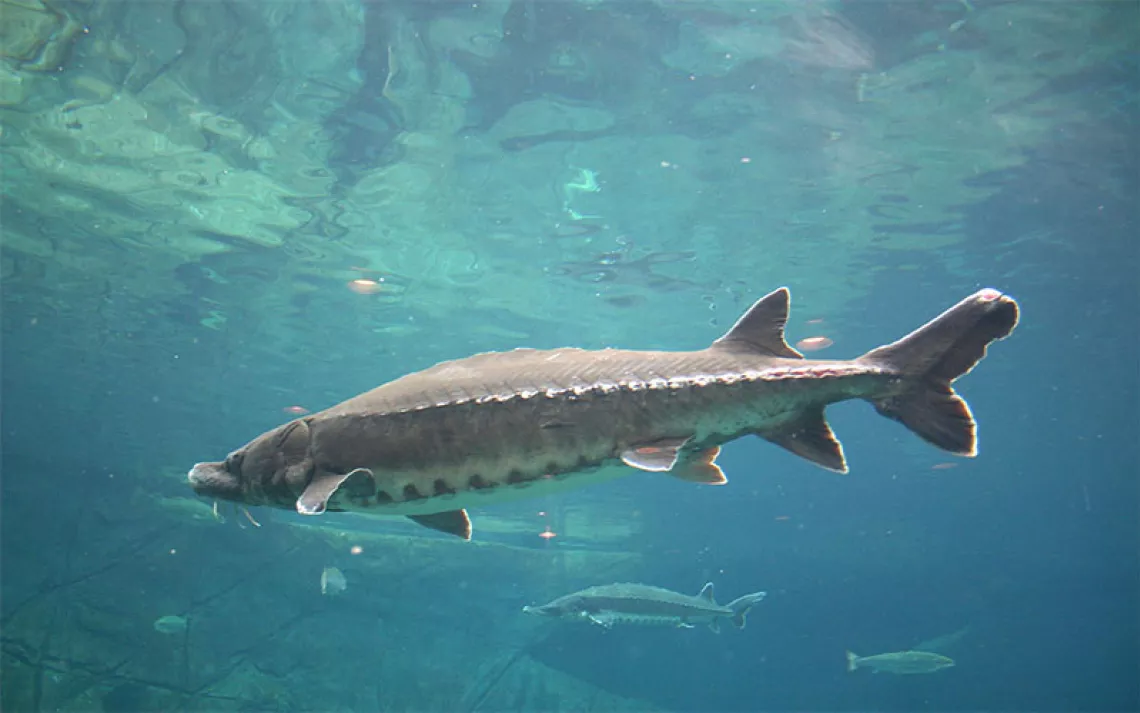

During the 20th century, Cabo Pulmo and the Sea of Cortez followed the traditional overfishing script. First came the fishing advancements: boat motors and gill nets and mass-produced fiberglass boats, then the masses of fishermen who adopted them: 20,000, give or take, in the Sea of Cortez by the 1970s. And then, the depressingly familiar outcome: fishery collapse. In 1942, for example, fishermen raked in 4.5 million pounds of totoaba. By 1975, their catch was less than 130,000 pounds—a 97 percent decline.

The fishing families of Cabo Pulmo suffered. Juan’s niece, Judith Castro, grew up in the '60s and '70s watching her father and uncles and brothers spend their days at sea; it was an era she referred to as “a time of desperation.”

“I can’t tell you how I suffered as a young girl, to see them come back, day after day, tired, thirsty, hungry, with nothing. Nothing,” Judith says. “My father told me how many sharks there used to be when he was a kid—so many! And then, they were gone. Finished. Dad would say, ‘We’ll never see those sharks again. Never.’”

The rest of Cabo Pulmo’s story should have been predictable. The fishermen would have traveled farther and farther to get their catch; their children would have left the village to go to towns and cities, looking for more profitable work. Cabo Pulmo might have disappeared entirely, replaced by all-inclusive resorts and golf courses like fishing villages in other parts of the world. I’ve seen reefs near these vanished villages, floated over their sandy skeletons as they surrender to encroaching algae. I’ve met the fishermen who remain. Wary of conservation efforts, they break moratoriums and bribe officials. I’ve seen fishing cooperatives become fronts for smuggling cocaine.

But Juan saw a very different future for Cabo Pulmo. If divers were paying him to see a dying reef, he thought, they would surely pay more to see a vibrant one. Within 24 hours of his epiphany, Juan had tracked down a professor from the nearby Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, and their conversation sparked years of study. Cabo Pulmo’s corals, researchers found, had been gouged by anchors, bashed by steel pipes, and poisoned from chemical fishing. And there was barely any marine life left.

Together, researchers and villagers petitioned for a marine park. It took a decade and a half, but by 1995, the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Reserve was established, protecting more than 27 square miles of ocean from fishing. Cabo Pulmo did not disappear. On the contrary, it had a magnificent marine renaissance.

♦

Professor Octavio Aburto has draped himself over the side of our boat, belly on the edge, hands and camera in the water.

“Johnson! Johnson!” he shouts.

Andrew Johnson, the post-doc working at Octavio’s side, takes two wobbly steps across the floor of the boat and grabs Aburto by the nape of his wetsuit.

“I’ve got you, my darling,” Johnson quips.

Aburto is the director of the Gulf of California Marine Program at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at U.C. San Diego and a professional photographer. Below us, sleek gray curves slither around the boat, their slightly rounded fins skimming the surface. Our dive master, Davíd Castro—who, delightfully, is Juan Castro’s grandnephew—throws putrefied chum into the thrashing water, while Aburto leans farther over the boat, maneuvering a camera encased in a glass dome wider than his head.

Meanwhile, the boat captain is calling out numbers to the group: “There are five. Here come two more! That’s seven—no—eight.” By the time Aburto gets his fill of photos, we’re surrounded by 10 flat-nosed silky sharks.

“Not bad,” Davíd says.

Davíd started scuba diving at five years old. He’s used to the magic of Cabo Pulmo: herds of silkies snaking around snorkelers, giant schools wheeling around divers in fish tornados. He once saw a school of big-eyed jack tuna 60 feet wide and 60 feet tall—from the seafloor to the surface. I ask him what that felt like. He shrugs, flashes his braces: "Normal.”

On our way to the next dive site, the whitecaps thrash with milkfish. Outfitted in scuba gear, we fall back into the sea and sink down to a reef shrouded in clouds of translucent shrimp. I spot mating pairs of the big-eyed jacks, the black males mirroring the silver females like shadows. The reef is dotted with 100-kilo snappers, mottled groupers, and grinning moray eels. Davíd floats by serenely, followed by Aburto and his camera.

Next, we dive the shipwreck. Within minutes, a dark silhouette looms ahead, a dozen feet high. But it’s not the ship; it’s a school of hundreds of silver graybar grunts and hundreds of yellow spottail grunts, moving en mass like an underwater planet. Swimming into the sphere, I’m engulfed in tails and beady eyes. Currents of fish stream around as I snicker streams of bubbles out of my dive regulator. Jacques Cousteau once called the Sea of Cortez “The World’s Aquarium.” I twirl among the fish. The aquarium is interactive.

♦

Octavio Aburto was one of the researchers who documented Cabo Pulmo’s marine miracle. While studying at Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, he took part in marine surveys along Baja’s coast. By 2009, 10 years later, he had raised the funds to replicate that study through Scripps Institution of Oceanography. For Baja as a whole—including two other marine reserves—ecosystems were stagnant or declining. Cabo Pulmo was a spectacular exception.

In order to capture the change in marine life, the researchers measured biomass, the physical space taken up by organisms. During a single decade, Cabo Pulmo’s marine biomass increased by a staggering 463 percent—the largest seen in any marine reserve on Earth. The number of apex predators increased by more than 1,000 percent.

The abundance of marine life made a large impact on the economy of Cabo Pulmo, but it didn’t happen right away, and it didn’t come easily.

“It’s not easy to give up fishing,” Juan Castro says. “It’s like giving up a drug addiction. It’s hard.”

Castro felt that the people of Cabo Pulmo had no choice; tourism was their only chance. That conviction was shared and fueled by the researchers who came to Cabo Pulmo, and by some of the younger Castros. But when Juan launched his dive shop, his clients were few and far between. Meanwhile, his brothers and nephews who still relied on fishing outside of the reserve were pushed into poverty.

“Those years were the hardest, the poorest, the cruelest,” says Judith Castro. “There wasn’t an alternative income yet, so they had to go really far to fish and spend all their money on gasoline. And there wasn’t much to catch.”

Caught in the gear-change between fishing and tourism, Cabo Pulmo stalled. But so many people had fought for so many years to establish the park that a consensus prevailed. There was no going back.

Then Castro's business began to expand.

“[Clients] would call and say, ‘Juan, I need three or four boats.’ And I only had one!” he says. So he would call his brothers and nephews and ask for them to take some of his clients. “I said, ‘Look, don’t waste your gas looking for fish—[the tourists] will pay you the second they step on your boat!’”

With time, the families of Cabo Pulmo began to get a taste for tourism, and tourists began to get a taste for Cabo Pulmo. Villagers launched snorkel and dive shops, restaurants, and rentable bungalows. Their income increased so dramatically that now, not only can they send their children to school, but they can also send them to the university that sent the researchers in the first place.

♦

The coalition that won the Cabo Pulmo reserve now wants to take its strategy global, starting with a fishing village in Jamaica. There have been four or five previous attempts to establish an offshore reserve there, but all have failed. But Aburto and several members of the Castro family—Davíd and Judith included—have been flying in this past year, telling their story in hopes it will inspire the Jamaican fishermen to establish their own reserve. If they’re successful, they may pave the way for a new future of marine reserves, one in which fishermen are the enforcers, and where a 463 percent increase in biomass is the rule of ocean recovery, rather than its exception.

But it takes a leap of faith. It takes a leader like Castro, the courage to risk one’s livelihood for the promise of something better, and perhaps a moment with a coral garden of God.

Can we count on such clarity?

Juan squints at me and his white mustache droops. “It isn’t easy, but look,” he points to the waves curling on the sand. “You have to be a damn idiot not to preserve this place.”

The sky blushes bright pink as the sun dips below the sea. The waves arc over the beach of Cabo Pulmo, mirroring the sky above, translucent as melted pearls. Espejismo.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club