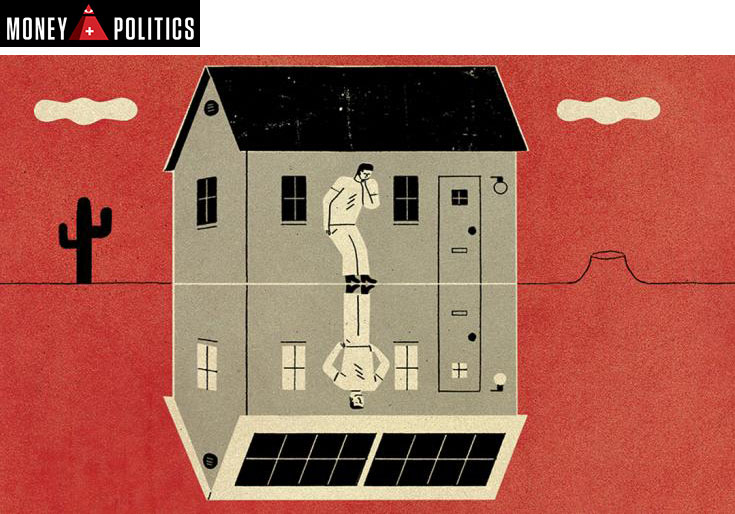

In Arizona, dark money is eclipsing the rooftop solar industry

Threatened by the rise of rooftop solar, Arizona utilities try to pack a state commission with their hand-picked candidates

Arizona has the perfect climate for solar power, so why aren't there more panels on rooftops? | Illustration by David Plunkert

For years, Kristin Mayes has been telling anyone who will listen that "Arizona should be the Saudi Arabia of solar power." A law professor at Arizona State University who specializes in energy issues, Mayes points to the dazzling sunshine that falls on Phoenix—an average of 211 sunny days a year, the most of any major U.S. city. "You'd think nearly every building here would have photovoltaic panels on the roof," Mayes says.

That makes sense, especially given the overwhelming support that solar power enjoys in the state. "Arizonans love solar," says Sandy Bahr, director of the Sierra Club's Grand Canyon Chapter. "It makes them feel more independent and not so tied to ginormous monopoly utilities." In a 2013 poll, 62 percent of Arizonans said solar power was their first choice for energy production. And residents walked the talk: In that year, Arizona installed more new solar capacity per capita than any other state.

Combine all that sunshine with solar's popularity—plus the fact that the cost of rooftop solar installation has dropped by half in the last few years—and one has to wonder: Why aren't there more solar panels in Arizona?

To solar advocates, the answer is as clear as the desert vistas. They blame the cozy relationship between the state's three largest monopoly utilities and the Arizona Corporation Commission—an obscure, five-member body that sets the rules for electricity generation in the state. At the heart of this relationship are millions of dollars in dark money: independent political campaign expenditures by shadowy pass-through organizations that aren't required to reveal their funders.

But let's back up to 2012, when solar power's future looked bright. So many people were putting up solar panels that Arizona was second only to California in adding solar jobs. On its website, a local installer captured the zeitgeist: "For solar power, the sky is the limit."

From the utilities' perspective, however, the sun-drenched sky was falling. A utility trade group warned members that privately owned renewable power, also known as distributed generation, could "transform the electric utility industry" and cause "irreparable damages to revenues."

The state's largest utility, Arizona Public Service (APS), took the message to heart and began trying to roll back the very programs that had launched Arizona's revolution in distributed generation. Mayes knows a thing or two about these measures; she led the effort to create them while serving on the corporation commission from 2003 to 2010. During her tenure, the group ruled that utilities had to pay owners of rooftop solar for any excess power put into the grid—a measure known as "net metering." It also required utilities to generate 15 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2025, with 30 percent of that total coming from distributed generation.

In 2013, APS sought to impose a monthly fee of $50 to $100 on solar customers, a charge that Arizona's largest newspaper warned "very well could wreck rooftop solar" in the state. Around the same time, the utility donated an undisclosed amount to two dark-money organizations that ran television ads and posted online media endorsing the utility's position on net metering. The donations to the conservative groups 60 Plus and Prosper Arizona were funneled through a political consultant named Sean Noble. According to an investigation by the Pulitzer-winning news site ProPublica, "Noble was tasked with distributing a torrent of political money raised by the Koch network, a complex web of nonprofits" set up by the hard-right billionaires Charles and David Koch. After a contentious hearing, the commission handed APS a modest victory, allowing the utility to charge solar customers a $5 monthly fee, while leaving the door open for hefty increases in the future.

When the utilities realized they couldn't eliminate regulations wholesale, they turned to a new strategy: replacing the regulators. Led by APS, utilities funded candidates who were likely to rubber-stamp their requests and poured millions of dollars into organizations like the Arizona Free Enterprise Club, which has links to the Koch network.

In 2014, groups with ties to APS and the Kochs spent at least $3.2 million to help elect two new commissioners, Tom Forese and Doug Little. APS refuses to confirm or deny that it was behind the donations, and a utility spokesperson insists that "APS is, and always has been, passionate about solar." Since they've been on the commission, however, Forese and Little have consistently shared APS's antagonism toward distributed generation.

Recently, the corporation commission has been rocked by a series of scandals, including one last December, when Chair Susan Bitter Smith was forced to resign after multiple conflict-of-interest allegations, one involving APS. It was up to Governor Doug Ducey to name her replacement. The Republican governor himself benefited from millions in dark-money contributions after he praised the Kochs at a high-roller affair they hosted during Ducey's 2014 gubernatorial campaign. So no one was surprised when Ducey appointed Andy Tobin, the former Speaker of the Arizona House of Representatives, who has received major donations from Arizona's largest utilities and heavyweights in the fossil fuel industry like ExxonMobil. In 2014, his largest direct contributions, totaling $12,600, came from the Koch brothers.

Like his colleagues, Commissioner Bob Stump has received direct campaign contributions from APS and the Salt River Project, Arizona's second-largest utility. He also benefited from dark-money expenditures targeting his Democratic opponents, including $62,520 from the Taxpayers' Voice Fund. APS admits its money went to the group but insists that it didn't know the funds would be used in the corporation commission election.

Solar advocates say that the stream of dark money is turning the corporation commission into a shill for big monopoly utilities. Arizona has already dropped from first to sixth place in solar installations per capita, and between 2014 and 2015, the solar industry shed 2,178 jobs—a 24.5 percent contraction.

But the Sierra Club's Bahr isn't about to surrender. On the contrary, she's gearing up for a battle this fall to elect commissioners who support Arizonans' right to produce renewable power—and to be fairly compensated for it.

"In the end, solar will prevail," she says. "The fossil fuel industry was never going to go quietly into the night, right? They're going to go kicking and screaming. But they're going to go."

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign (beyondcoal.org).

This article appeared in the September/October 2016 edition with the headline "Sun Blocked."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club