Oakland Defeats Proposed Coal Port While Bay Area Continues Exports

Residents complain coal trains, dust threaten public health

Photo by iStock/Kenneth Sponsler

The flailing U.S. coal industry suffered a significant setback last week when the city council in Oakland, California, voted unanimously to block coal shipping from a new bulk commodities terminal under construction at the Port of Oakland. As recently as five years ago, the coal industry was eyeing at least six locations across the West Coast as possible sites from which to ship coal to East Asia. The proposed coal ports represented a desperate, last-ditch effort to maintain market share as utilities back away from coal due to the low price of gas, new federal rules to stanch carbon pollution, and dogged pressure from the Sierra Club and other environmental groups. Public opposition has succeeded in sinking almost all of those proposed coal ports, including the largest: a massive terminal planned for Cherry Point, Washington. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ruled that a coal port there could impact local fisheries and violate the federal government’s treaty obligations to the Lummi Nation.

The proposed coal port in Oakland generated opposition from environmentalists and community groups in 2014. That’s when officials in Utah began talks to contribute $53 million for the construction of the new bulk commodities terminal. In exchange, they wanted a guarantee that a certain amount of materials shipped through the port would come from Utah—including some of the 16 million tons of coal mined there annually. Many Oakland residents were against the idea (76 percent, according to a Sierra Club poll), fearful that a coal export terminal would exacerbate the poor air quality that already plagues neighborhoods near the Port of Oakland. Environmental groups complained that increased coal exports were inconsistent with the state’s aspiration to be a leader in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The dispute turned ugly when a shadowy group called Jobs 4 Oakland sent out a race-baiting mailer attempting to pit Oakland’s large African American community against environmentalists.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

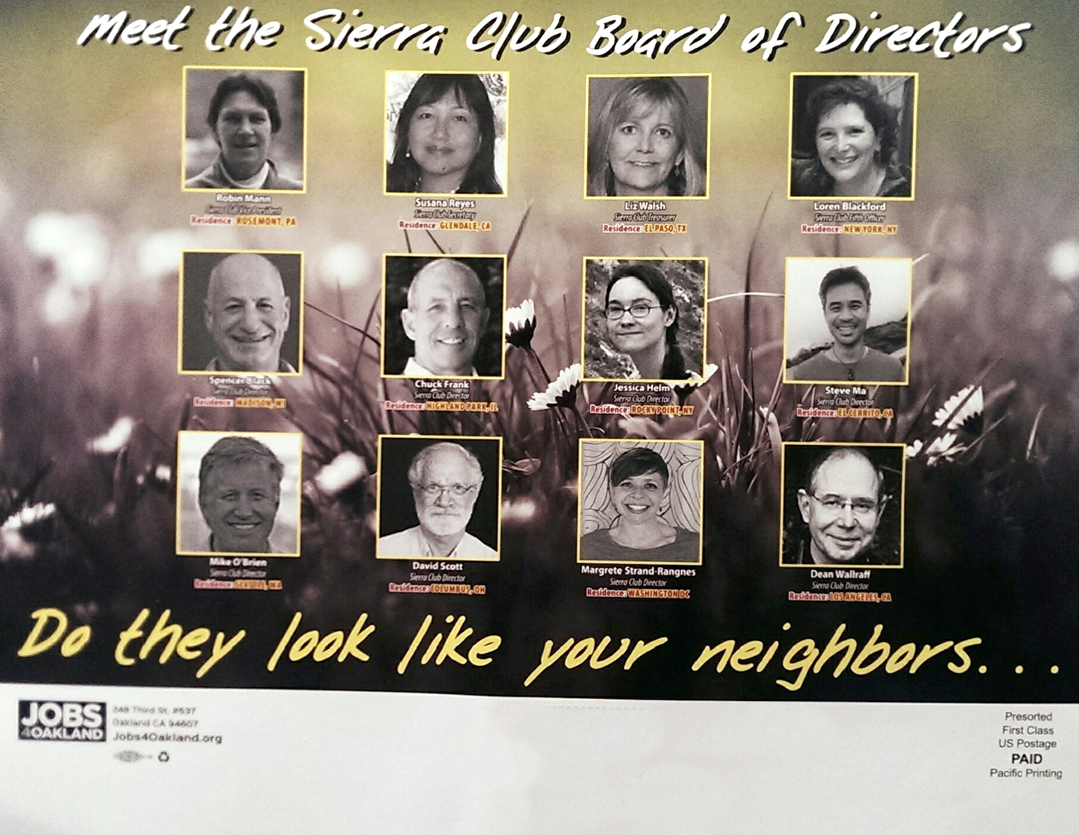

Trolling at its worst: A last-minute, pro-coal-port mailer from a shadowy group called Jobs 4 Oakland was a clear attempt at race-baiting, especially since it failed to include the two African American members of the Sierra Club Board of Directors: Michael Dorsey and Club president Aaron Mair.

In the end, Oakland leaders dismissed the notion that this was some kind of standoff between jobs and the environment. “No person should ever have to choose between a job and their health and safety,” Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf told the Los Angeles Times. “There are plenty of other commodities. Plenty of other economic activity that is going to be successful in this project.”

The smackdown of the proposed coal port represents yet another victory for what author-activist Naomi Klein has dubbed the “Blockadia” movement: the effort by environmental groups and allies to stop any new oil and gas projects, pipelines, or leasing of government lands for fossil fuel extraction as a necessary step toward transitioning to a clean energy economy.

But all of the attention given to the proposed Oakland coal port has overshadowed an important fact: Coal is already being exported from the San Francisco Bay Area, and those exports already constitute a public health risk and a kind of environmental injustice.

In the heavily industrialized, largely poor and working-class city of Richmond (located about 25 miles north of Oakland), the privately owned Levin-Richmond Terminal has been exporting coal since at least 2013, and petcoke—a byproduct of petroleum refining—for much longer. Though exact numbers are scarce, the best estimates suggest the port is shipping somewhere between 360,000 metric tons and 1.2 metric tons of coal and petcoke a year, with Japan and Mexico the main recipients.

(The Richmond facility isn’t the only site in California currently exporting coal: The black rock also flows out of the Mountain West and toward Asia via the Port of Stockton, the Port of Los Angeles, and the Port of Long Beach.)

Richmond residents say the trains shed significant amounts of coal dust as they pass through their community, and that this dust poses a health risk. According to BNSF Railway, as much as 645 pounds of coal dust escapes from each coal car in the course of a 400-mile trip. (The Levin-Richmond Terminal disputes that figure.)

Sylvia Hopkins is one Richmond citizen who has expressed concern about the trains. She’s a 72-year-old retiree living in Atchison Village, a former World War II-era housing complex for Kaiser Shipyard workers located in Richmond’s “Iron Triangle”—so named because it’s bound on three sides by railroad lines.

“The dust in my yard has increased, and it has changed,” Hopkins says. “It used to be like brown dust. Now, it’s black and it’s grimy. It has increased quite a bit, so much so that I took a slightly damp paper towel out to my backyard table, and it came away black and gummy. Those of us who live around here, we really don’t have a lot of money, and I’m one of those. We try to make our backyards nice and livable. But I don’t really enjoy being in my backyard anymore, because everything is dirty. You have to do major cleanup before you go out there. It’s quite discouraging. But the most important fact is what we are breathing in.”

Richmond is a classic example of environmental injustice. The city is mostly home to people of color (22 percent of residents are African American and 37 percent are Latino), and a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line. Richmond is also home to a gigantic Chevron oil refinery that processes about a quarter-million barrels of crude oil a day, making it the number one greenhouse gas emitter in California. In addition to being a major source of CO2 emissions, the refinery and the city’s many other industrial operations are likely the cause of elevated levels of particulate matter, a major contributor to pulmonary diseases. Richmond residents have high rates of child and adult asthma; 15 percent of area residents have asthma, among the highest percentages in California. Air quality has long been a public health issue in the city. A 2010 study conducted by researchers from UC Berkeley and Brown University found that indoor air quality in Richmond homes is worse than the air quality outside and detected 104 toxics inside houses.

For Hopkins, the coal dust blowing off the trains is one more environmental hazard to contend with. “What they found that is bad for us outside, is also bad for us inside, but in greater degree, because it comes inside and gets trapped in here,” Hopkins says. She’s also worried about what effect the coal dust might have on the small garden where she grows tomatoes and basil, along with an apple tree and a pomegranate bush. “I have spent money bringing in soil so I could grow stuff in raised beds. But now I wonder if there isn’t something depositing on my soil.”

Environmental groups have been concerned about the Levin-Richmond Terminal’s handling of petcoke for years. The petcoke comes from the nearby Phillips 66 oil refinery where, according to Andres Soto, a campaigner with Communities for a Better Environment, from Highway 4 “you can see this big mound of petcoke dumped into a pile and then onto a conveyor. You can see the engines of the Richmond-Pacific Railroad moving these cars into place.” In 2012, San Francisco Baykeeper sued the terminal for violating the Clean Water Act by, according to the group’s allegations, allowing petcoke to blow off of conveyors and into the bay. The company settled the lawsuit in 2014 without admitting wrongdoing and agreed to enclose its conveyor.

“This is just another contributing factor to the environmental injustice that people suffer in Richmond due to the activities of the fossil fuel industry,” Soto says.

“I’d like to see them stopped,” Hopkins says of the coal trains. “For me, it’s unconscionable.”

There are, however, few options available to the Richmond residents and environmental groups who are concerned about the trains. The Levin-Richmond Terminal has been operating for decades, and there are no conditions in its use-permit prohibiting the shipment of coal or petcoke. In May 2015, the Richmond City Council did pass, by a six-to-one vote, a resolution opposing the transport of coal in open rail cars, but it was nonbinding. “By the time we found out about it [the coal trains], it was already in place, and there wasn’t anything that we could do about it,” Soto says.

Soto’s advice to residents in other communities considering a coal port: Stop it before it’s too late. “The lesson here is prevention,” he says.

Fortunately, that’s a lesson that the city leaders in Oakland appear to understand well.

What You Can Do

Oakland City Council will cast a final vote on 7/19/2016 to block coal exports. Call 415-236-3166 to express support.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club