To Understand the Natural World, First Pay Close Attention

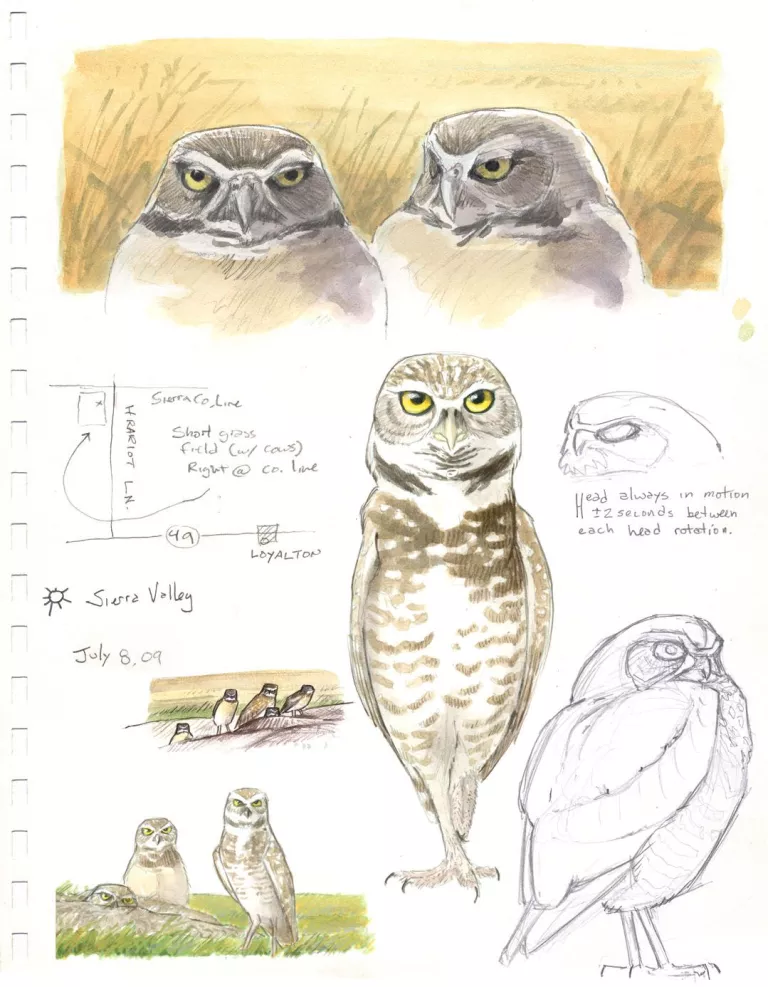

Sketches from The Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling by John Muir Laws (Heyday, March 2016).

Editor’s note: To really explore and understand the outdoors, it’s best to have a good field guide to help make the landscape legible. For those of us who live in California, there are few resources that top the books by John Muir Laws. His Field Guide to the Sierra Nevada and his Pocket Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area combine beautiful illustrations with exacting biological information on birds, beasts, and plants. Laws’s latest book, The Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling, offers tips on how you, too, can become a naturalist-illustrator. Here’s an excerpt.

—Jason Mark

The foundation of natural history is careful and specific observation with rigorous and exacting note-taking. Much of what we know about the natural world today comes directly from the journal entries of naturalists and scientists. When you record information in your journal, you are adding to that body of knowledge and building your understanding of the natural world.

Yet when you go outside to journal, especially in a new place, the vastness of possibility can feel overwhelming. It is hard to know where to begin, and it is easy to feel pressured to capture every aspect of an experience or landscape.

Writing and drawing in your journal improve your ability to observe, process, and remember your thoughts and experiences. In time we all forget what we have seen or modify our memories. Anything observed but not put down on paper is lost to science, posterity, and in time to you as well. If you record them in a journal, your ideas and discoveries will stay with you both physically and mentally.

When I was young I took a nature journaling workshop with Clare Walker Leslie and Hannah Hinchman in Grand Teton National Park. These masters of nature journaling gave each of us a piece of string and instructed us to go outside, put the string on the ground in a circle, and record everything within the circle. In the vastness of Grand Teton National Park, that small frame gave me the focus to make discoveries. Within a huge and spectacular landscape, I found an equally beautiful and rich world inside the confines of that one piece of string. After exploring that world for hours I felt connected to and intimate with the place as a whole.

If you limit your focus when you journal, you will not feel overwhelmed by how or where to begin. Asking and following questions is one place to begin your experience of journaling. Each question will give you a point of departure and an immediate invitation to interact with some aspect of the natural world. Use the questions to guide your journal entries or to jump-start your observations. Even though they are not physical pieces of string, such questions will help you to look at nature differently and will lead you to discover the million tiny worlds that exist in any given place.

To make your observations valuable to science and help you keep track of your experiences, include where-and-when data on every page. It only takes a few seconds to do and converts any journal page from an anecdote to a scientific record. A pretty picture of a bird is just a pretty picture of a bird. However, if that same picture is connected with information about where and when the bird was seen, it becomes a rich scientific record. Details from plumage to behavior will change over the year and between locations. By connecting observations with “when” and “where,” you will be able to answer many questions from your notes. The fact that you saw a Painted Redstart is nice. A sketch or note that describes its behavior or plumage is better. Those same notes connected with date and location information are personally more interesting and scientifically more useful.

When you write your notes, you have no way of knowing what questions you will ask of your data in the future. Date, location, time, and weather will give you the context in which an observation was made. This is called metadata (the data about the data), and it should be appended to every observation or journal page. Make it a habit to include the location and “date stamp” on every page (ideal) or at the start of each day’s notes if you use a bound journal. Including metadata in your notes reinforces the relationship between what you are seeing and when in the year and where on the earth you are.

There is so much you could do in your journal that it is hard to know where to start. Giving yourself a finite project or question to explore will help you to concentrate and discover. Each project is a frame through which you can observe and discover new worlds.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club