Sacred Be Dammed

Photo by Emily Mount

Rounding a bend along the McCloud River, I pull my truck off the road, roll down the window, and listen. The roar of whitewater is unmistakable, a welcome sound after passing miles of sedentary, quiet water behind Shasta Dam. I have come to see the meeting place of river and reservoir, where the wild McCloud is tamed in California's largest man-made lake.

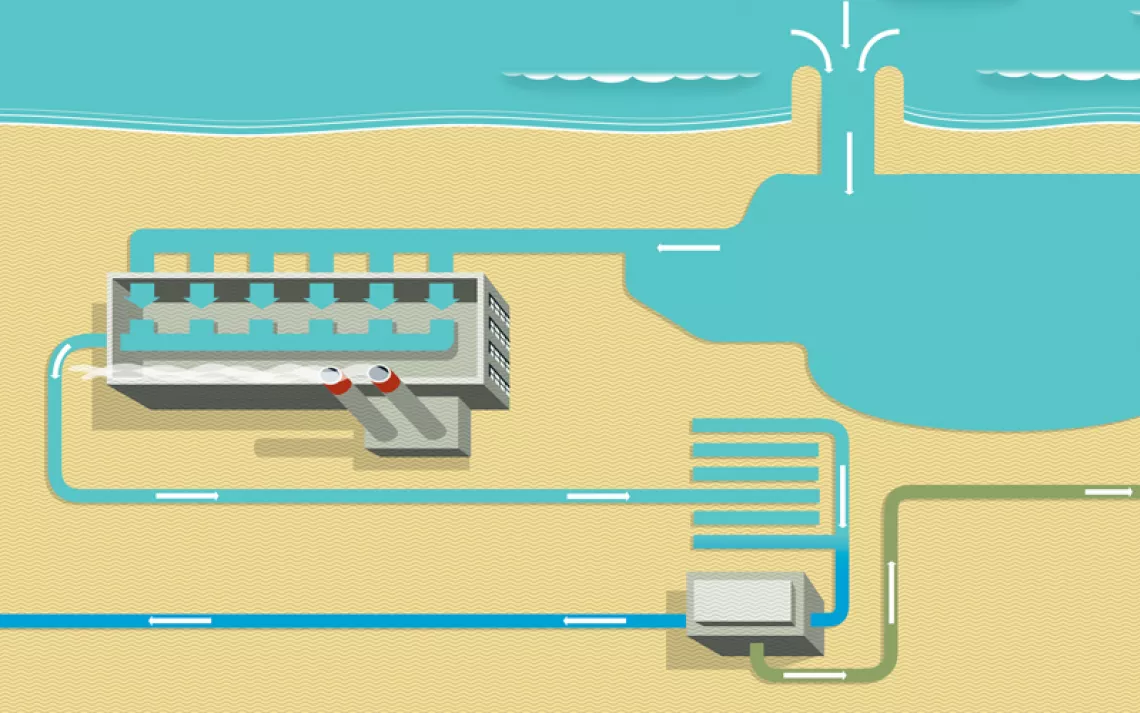

Shasta Dam and its lake are currently embroiled in California's ongoing water emergency. The multiyear drought has sent California's Department of Water Resources and state leaders scrambling to both cut water usage and to find new sources of freshwater. Last year, Senator Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat, put forth a $1.3-billion bill to meet the needs of her parched state. The bill contains plans for ocean desalinization, water recycling, mandates for agricultural water conservation, and new water storage projects—including increasing the height of Shasta Dam by as much as 18.5 feet.

Raising the dam would swell Shasta Lake by 13 percent and theoretically supply a steadier source of freshwater to Central Valley farms and distant cities. But it also would flood about 5,000 acres of land, including sites sacred to the Winnemem Wintu, a Native American tribe.

According to their oral history, the Winnemem Wintu, or Middle Water People, have lived along the McCloud River since "time immemorial." Prior to European-American contact, their population was around 15,000 to 20,000. Disease and bounty hunting of California's indigenous people during the Gold Rush era reduced the Winnemem Wintu to 395 individuals by 1910. Today's 150 tribal members fear for the future of their culture if much of their remaining ancestral land disappears under water.

Forty sacred sites, including rocks, pools, groves of trees, dance circles, and burial sites would be flooded or otherwise disturbed by raising the dam. Winnemem Wintu frequently use these sites for activities including rites of passage, physical and spiritual healing, and developing childhood connections to sacred places. If the people are unable to visit their sacred sites, "the tribe is at risk," says Caleen Sisk, the chief and spiritual leader of the Winnemem Wintu. "Winnemems are more than just Indian by degree of blood. This is a way of life. If you don’t know where your sacred places are…you're really not [Winnemem] anymore."

This is not the first time that the Winnemem Wintu’s culture has been threatened by Shasta Dam. At one time, the tribe’s ancestral land included 26 miles of deep river canyons around Mount Shasta—ideal terrain for dam construction. Engineers broke ground for Shasta Dam in 1937. "All non-Indians were relocated [by the government]," Sisk says. "We just had to scatter. Many people stayed in their houses until the bulldozers came. They had nowhere to go." By the time Shasta Dam was completed in 1945, the 602-foot dam was the tallest man-made structure in California and 90 percent of the Winnemem Wintu's homeland was underwater.

Today, much of the water from Shasta Lake is channeled hundreds of miles south to the Central Valley, epicenter of California’s industrial agriculture. Located southwest of Fresno, the Westlands Water District would be the main beneficiary of the Shasta Dam raise, though urban centers from Los Angeles to as far south as San Diego would also receive Shasta Lake water. Westlands is the largest agricultural water district in the United States and the private water distributor for 1,000 square miles of farmland. Almonds, processing tomatoes, and pistachios are the dominate crops. According to the conservation group Friends of the River, 400 farmers in the Westlands Water District use more water than all of the residents of Los Angeles and San Francisco combined.

Westlands has promised to cover $200 million of the estimated $1 billion cost to raise the dam. Also, the water district has already invested more than $35 million to purchase some 3,000 acres of land around the reservoir.

The Winnemem Wintu are not a federally recognized tribe, so do not possess a government-to-government relationship with the United States that other native nations retain. Their legal standing to oppose the dam is like that of any private stakeholder. In 2004 and 2014, the tribe held war dances at Shasta Dam to protest the dam raise with song, dance, fasting, and prayer. "We feel [Shasta Dam] is a weapon of mass destruction that has destroyed our ability to have homes on the river," Sisk says. "This is an ongoing cultural genocide."

For its part, the Bureau of Reclamation acknowledges that the dam raise would impact cultural resources. The agency’s draft feasibility and environmental impact report on the project says the Winnemem Wintu’s concerns remain an “unresolved issue.”

Many environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, oppose the idea of raising the dam. In addition to the cultural survival issues, conservation organizations and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service believe the dam raise would not improve the state of the endangered downstream salmon runs.

The Bureau of Reclamation claims that increasing the size of the dam would allow a steadier supply of cold water downstream, which would help endangered fish. But environmental groups and the Winnemem Wintu note that if salmon survival is the goal, there are significantly less expensive and more effective ways to help fish, including habitat restoration and assisting salmon around the dam. "All those things you can do without raising the dam, and there would be distinct benefits for the salmon," says Steve Evans, a consultant with Friends of the River. “But enlarging the reservoir alone does not actually have any value for salmon."

Instead of pursuing a costly and controversial plan to raise Shasta Dam, says Sierra Club California director Kathryn Phillips, the state should be examining ways to fundamentally change the way it uses, stores, and moves water. "I don't think there's any time in the last 25 years when California has had as great an opportunity to do better on water than right now,” she says. “The public is attuned to it. They care about it. They care about the drought, and they're also very sensitive to environmental issues.”

Sitting on the banks of the McCloud River, I watch whitewater frothing over jagged rocks before it is swallowed by Shasta Lake. Just upstream, the Winnemem Wintu's sacred sites wait for the people to return. Caleen Sisk's words echo with the water: "There's no champion. There's no elected official who is worried about this. There's no representation in the government whatsoever. And the Bureau of Indian Affairs refuses to even acknowledge that we're Indians. So what do you do? What can you do? You just keep going and hope."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club