Local Roots vs. Industrial Agriculture

Big Ag may feed millions but tiny producers take the planet to heart.

Do you really want to put that in your mouth? Despite a few notable cases—such as 2012's uproar over the meat industry's use of "lean finely textured beef" (a.k.a. "pink slime" or "soylent pink")—Americans pay scant attention to what we eat. Our highly mechanized and largely out-of-sight industrial-agriculture system makes it all too easy to fill up on cheap processed foods made with unpronounceable ingredients. The true cost comes in human health and environmental degradation: livestock production, for example, accounts for more greenhouse gas emissions than all the world's cars, planes, trains, and ships. Combined.

Do you really want to put that in your mouth? Despite a few notable cases—such as 2012's uproar over the meat industry's use of "lean finely textured beef" (a.k.a. "pink slime" or "soylent pink")—Americans pay scant attention to what we eat. Our highly mechanized and largely out-of-sight industrial-agriculture system makes it all too easy to fill up on cheap processed foods made with unpronounceable ingredients. The true cost comes in human health and environmental degradation: livestock production, for example, accounts for more greenhouse gas emissions than all the world's cars, planes, trains, and ships. Combined.

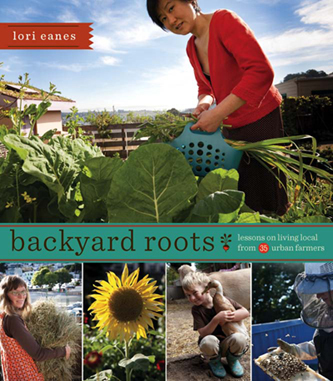

But as photographer and frequent Sierra contributor Lori Eanes documents in her book, Backyard Roots (Skipstone, 2013), which we showcase on the following pages, there are almost as many ways to produce healthy food on a small scale as there are items to eat.

Jonathan Chen, a cancer survivor, found solace in growing vegetables, first on a small organic farm in France and later in Seattle, where he started a children's community garden. "We used to be in sync with the natural rhythms of the seasons," Chen says. "Now we don't know how to eat. We don't even know that vegetables have seasons."

By turning their backyard in Vallejo, California, over to fruits, vegetables, chickens, turkeys, rabbits, and goats, Rachel Hoff and Tom Ferguson freed themselves from having to set foot in a grocery store. Well, almost: "Soy sauce and apricots [which require sugar to preserve] did me in," Hoff blogs.

With help from a U.S. Department of Agriculture loan, Alex Winstead started a flourishing organic, green-energy-powered mushroom farm in Bellingham, Washington, and now he helps spawn other fungus growers. On a hostel's rooftop in the heart of Seattle, Lee Kindell harvests plants and fish from his handmade aquaponics system. These characters are just a sampling from among Eanes's three dozen very personal stories of how ingredients can be seen, touched, smelled, and celebrated as they make their way to your table.

For perspective, we include sobering visual reminders of our mega-agriculture system run amok: tuna species fished to the brink of extinction, "cage-free" chickens crammed together, and strawberries and fungi coated with pesticides.

Considered together, these photos make stark the yin and yang of modern food production. In the end, we hope one thought lingers on your palate: The closer you can be to your food—before it becomes your food—the better.

Mushrooms never sleep

Alex Winstead learned about fungiculture while at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. When he graduated, he started growing mushrooms in his basement and garage and selling them at farmers' markets.

After being mentored through a local organization called Food to Bank On and securing a U.S. Department of Agriculture loan, Winstead bought 2.5 acres in Bellingham and started a micro-farm called Cascadia Mushrooms.

He built two greenhouses and a warehouse and moved his residence into the warehouse's second floor. Downstairs, he cultivates shiitake, reishi, several varieties of oyster, lion's mane, wine cap, turkey tail, and pioppino. His painstaking, multistep process involves mixing sawdust sourced from local mills with mycelium spawn and incubating the cultures for up to three months.

He and his four employees spend two to four hours a day picking and sorting. "Mushrooms never take a day off," Winstead says. "We harvest on Christmas." He also helps people grow their own mushrooms and sells starter kits on his website.

"Mushrooms have a huge role in nature," he explains. "They're the first step in a chain of events that create soil."

How to quit the supermarket

How to quit the supermarket

In 2010, Rachel Hoff and Tom Ferguson watched a documentary called No Impact Man, in which New Yorker Colin Beavan attempts to bring his family's environmental footprint down to zero.

Inspired, Hoff and Ferguson decided to stop buying nonlocal food, which meant grocery stores and restaurants were verboten. The couple revved up their quarter-acre backyard garden in Vallejo, California, into a full-on urban farm. In their second year, they harvested more than 1,200 pounds of organic produce, including 45 pounds of strawberries, as well as more than 2,300 eggs and 250 pounds of meat, keeping a blog to document their progress. They buy only what they can't make or grow at home, which isn't a lot.

Hoff's tips for quitting the supermarket include starting small (like giving up processed foods), joining a community-supported-agriculture program (a CSA), and being willing to cook all the time. "It's more of a priority for us to make a good meal from scratch and eat it together instead of watching TV," Hoff told the San Francisco Chronicle.

Raise a fish, save the world

Atop a hostel in the heart of Seattle, Lee Kindell nurtures an aquaponics system handmade from reclaimed materials, including a horse trough. The 100-gallon closed loop system is stocked with dozens of tilapia whose poop helps grow herbs, strawberries, and other crops in a separate tank. Even with his small setup, Kindell harvests up to 50 pounds of fish every three or four months. "Tilapia are like rabbits of the water," he says. "All they do is eat and multiply."

Kindell's aquaponics display—along with his chickens, bees, and rooftop garden—makes many of the 50,000 people who stay at his hostel each year rethink where and how they get their food. "We have to bring farms into the city if agriculture is going to lower its carbon footprint and also feed the masses," he says. "I really believe that the grassroots urban-farm movement can have a permanent impact on a global scale."

Chicken heaven/chicken hell

When Jonathan Chen was a student at Ohio's Oberlin College, he thought he was destined to be a biology professor. Then, during his sophomore year, he was diagnosed with bladder cancer. After months of treatment and two surgeries, a healthy Chen returned to school. But he no longer wanted to be a professor. "I wanted to do something that made a difference," he says, "but I had no idea what that was."

His search for direction led him to France, where the group World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) hooked him up with a small farm in Clairac. There, he had an epiphany: "It was like I had never tasted a tomato before." When he got back to the U.S., he took a job at Seattle's Danny Woo Community Garden, where elderly Asian immigrants tend their plots.

Chen is proud of two innovations at the community garden: He introduced chickens, which provide eggs and entertainment, and he started a children's garden. "To keep the legacy going," he says, "the kids need to learn how to grow the food of their culture."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club