Leading Edge

Denmark supplies three out of four of the worlds offshore wind turbines, and it's on track to be free of fossil fuels by 2050

I slip off the curb on my borrowed Danish bicycle (black, steel, simple) and enter the great river of the morning commute into Copenhagen. From the sidelines it looked daunting, like a massive peloton sprinkled with supermodels. But you don't get more than half of the city's population commuting by bike if doing so is a frightening experience. Every major street has a wide bike lane completely segregated from motorized traffic and parked cars. Parents taking little kids to school on comfy cargo bikes stick to the right, folks late for work zoom by on the left. Almost no one wears a helmet.

Soon I'm breezing past crowds of pedestrians and buses so easily that it's like flying in a dream. I head for Langelinie, the harborside promenade famous for its statue of the Little Mermaid, eternally damned to serve as a backdrop to tourist selfies. Beyond her shapely shoulders is a row of wind turbines clustered around the city's water treatment plant. A little over a mile farther out in the harbor is the 20-turbine, 40-megawatt Middelgrunden array, an important early step in Denmark's commitment to renewable energy. It's tiny by today's standards but venerable in its 13th year of operation. When the weather allows, boats take tourists to visit it.

Respects paid to the pre-Disney mermaid, I set out for the city center. A huge banner outside Den Frie art museum invites passersby to "Feel now, how the future comes closer." For Denmark, that future includes saying farvel to fossil fuels. And it's coming closer fast.

To review, Denmark is that little country on top of Germany, otherwise surrounded by water. To the east is the Baltic Sea, to the west the North Sea; Norway lies across a channel called the Skagerrak to the northwest, and Sweden across the Kattegat to the northeast. The takeaway: lots of water, much of it fairly shallow, and lots of wind.

Aside from sea and wind, Denmark doesn't have much in the way of natural resources, but Danes are clever about working with what they have. Over the centuries, they used their proximity to some of Europe's most important sea lanes to become a major maritime power: A.P. Moller-Maersk is the world's largest container ship operator (and, until recently, was the world's largest builder of them). Danes were also quick to realize the potential of wind power. As early as the 1970s, they were investing in small community wind farms, attracted by novelty and a desire for self-sufficiency. (The 1973 Arab oil embargo hit Denmark very hard.) Generous governmental subsidies didn't hurt. Danes got used to seeing turbines sprouting from farmers' fields—and profiting from them.

Now there are 4,737 onshore turbines in this country the size of Maryland, and 519 more offshore. Wind accounts for more than a third of national electricity consumption; Danes use more wind power per capita than any other nation. By 2020, they intend to get 50 percent of their electricity from wind; by 2050, when the country's electrical grid goes off fossil fuels altogether, that number may hit 70 percent. (The rest is expected to come from solar and biomass.)

Consequentially, wind is also a major employer in Denmark. Five hundred companies supply the necessary goods and services, providing more than 27,000 jobs. That's more people than are employed by the Danish military.

If wind turbines are going to play an even larger role in Denmark's future, they need to be tested today. I'm in the lovely city of Odense, taking a bus to the inauguration of a shiny new test facility where turbine manufacturers can put new models through their paces in a controlled setting. It's located at the old Maersk shipworks northeast of town, now retooled as the Lindo Offshore Renewables Center.

Visiting American Tom Edson, an electrical-reliability consultant from Pennsylvania, explains the need to stress-test wind turbine prototypes. "You have a 40-ton gearbox up there, you'd think it would be bombproof," he says. "But the force of the wind is so powerful, it's almost godlike."

The country's wind people are very excited about this event. A former prime minister is here, as well as a representative of the Maersk family, which in maritime Denmark is practically royalty. There's champagne and tasty little salmon smørrebrød. Outside, a brass band of elderly former shipworkers playing "The Colonel Bogey March." The jaunty music is the perfect soundtrack to what is transpiring above: a 300-foot gantry crane cinematically hoisting the 750-ton foundation to a giant turbine and slowly rolling it overhead. If it were to fall, it would wipe out the Danish wind industry, but no one seems concerned in the least. At first I assume that the awe-inducing scene has been orchestrated for the gathered press, but it soon becomes clear that Bladt Industries, a steel contractor on the site, is just conducting business as usual, moving the steel behemoth in line with four others awaiting shipment to a German wind farm in the Baltic.

Inside the giant test facility there are speeches. The former PM speaks in Danglish—"We have new jobs, new muligheder [possibilities] for Danish industry." The Maersk princess presses a big red button, which starts a motor spinning at the front of the nacelle that towers above us, bigger than a bus. The nacelle is the business end of a turbine, holding the generator behind the blades where the power is actually produced. Afterward we clamber four stories up to see the giant testing equipment (which fortunately is no longer spinning), trying not to spill our champagne on it.

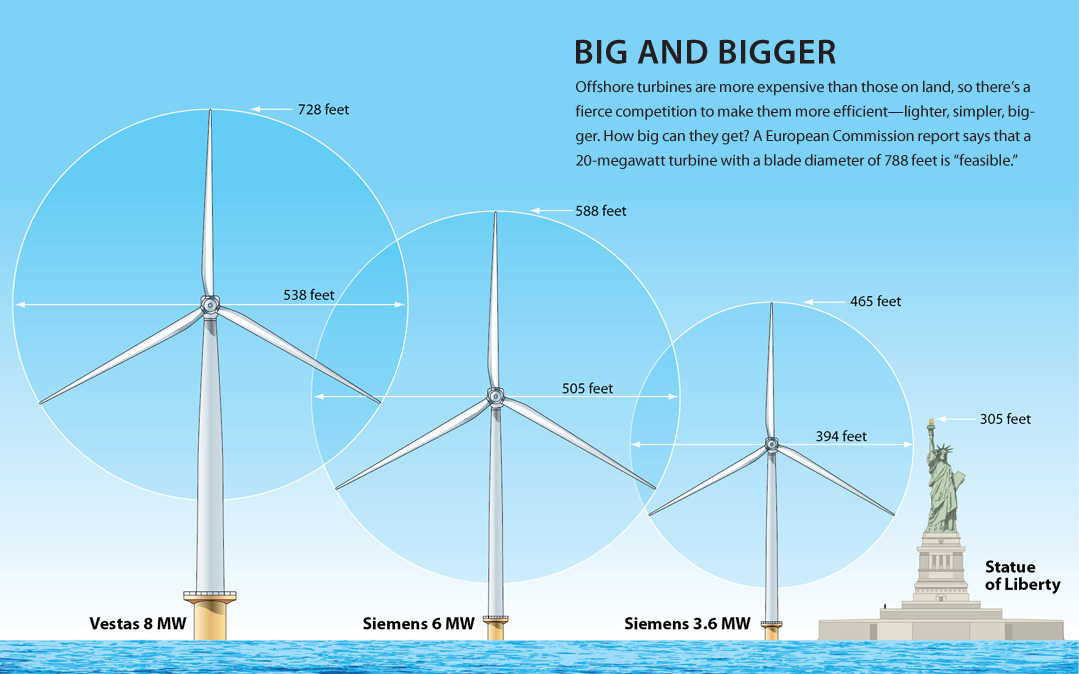

"Here we can test new types of nacelles to the extremes," says Franz Hubl of GE Power Conversion—part of an entourage of GE folks at the event. The equipment can simulate, say, a storm in the North Sea, but without the enormous expense of setting up a turbine there. Hubl's hope is that this ability will give those planning new wind farms the confidence to go with cutting-edge designs, rather than "equipment that has been tested maybe five years ago." That's like dog years for offshore wind, which is roughly twice as expensive as onshore wind and desperately needs to increase efficiency. The German company Siemens is now building 6-megawatt turbines, and Danish wind giant Vestas is testing an 8-megawatt model. They're vastly more powerful than current turbines, but potential buyers need confidence that the expensive whirligigs will work.

The agency responsible for incorporating unprecedented amounts of renewable energy into the Danish grid is Energinet.dk, which is housed in a large, open, ultramodern building outside the booming industrial town of Fredericia. It's noontime, and scores of mostly young energy experts are eating catered lunches at tables next to tinkling fountains. High above, a group of visiting energy professionals (plus yours truly) is being ushered into the inner sanctum, the control room for Denmark's grid. ("No photos, please!") One waggish visitor jokes that we should be careful lest we turn off Copenhagen.

It looks like a war room. Technicians scoot around on rolling chairs, monitoring dozens of computer screens; in the background, a wall-filling display pulses with real-time energy demands and outputs. Interpreting them, says senior engineer Thomas Krogh, is partly a matter of intuition: "Sometimes you can just kind of feel what's going on."

The wall display shows the country as a sequence of power sources grouped along power-line corridors, like a big-city transit map. Crucially, that map extends well beyond Denmark. Also being tracked are the massive hydropower works of Norway and Sweden, Sweden's three nuclear plants, and the wind farms and coal plants of northern Germany. A temporary oversupply in Denmark has a guy calling his counterpart in Sweden, which could use a boost. "We know everything about each other," Krogh says of Denmark's neighbors. "We have no secrets."

Key to the system is timely information. Meteorological data are updated every six hours and electricity prices hourly. "The more information you have," says Krogh, "the more slow-acting resources [like wind] you can use." Denmark is part of the "Nordic balancing market," which includes large amounts of cheap, emission-free hydropower in Sweden and Norway. On windy days in Denmark (a blustery one last December produced 122 percent of the country's electrical demand), Norway and Sweden are happy to turn off their hydro turbines while they buy Denmark's excess. "Neighboring hydro is really a good friend," says chief consultant Anders Baunhoj Hansen. Even better, though, would be a way to store the excess at home. "What do you need most that you don't have today?" someone asks. Without hesitation, he replies: "Electric vehicles."

I've just pulled into the parking lot in front of the big Siemens factory outside the town of Brande. Some 3,500 people live there, about the same number that work in the factory, so there are a lot of cars—none of them electric, so far as I can see, despite electric cars' exemption from a registration tax of up to 180 percent levied on gas and diesel vehicles. (The Danes I talked to all suffered greatly from range anxiety.)

Siemens has a laudable but fanatical focus on safety. Visitors are garbed from start to finish in safety shoes, safety vests, and safety glasses, and if you diverge from the clearly marked safety path, someone will run over and ask you to please stay safe. Beyond the usual concerns in a working factory assembling multiton components, there are also invisible forces at play that you wouldn't want to come too close to.

Brande is where the company builds nacelles; the factory for blades is farther north in Ǻlborg. Siemens's bread and butter is the 3.6-megawatt model that it's been building for years—it's the one used in the world's three biggest offshore wind farms: the London Array and Greater Gabbard in the United Kingdom and Denmark's Anholt, the country's largest offshore wind farm to date. (It will also be employed at Massachusetts's Cape Wind, the 468-megawatt wind farm now cleared for construction off Cape Cod.) But what they're building today is a "direct drive" 6-megawatt nacelle that dispenses with gears in favor of 648 powerful rare-earth magnets to withstand the wind's godlike force. I'm granted a quick look inside the building where they're being assembled. ("No photos, please!") The magnets are installed by blue robot arms in a glassed-in room painted bright red, where humans are not allowed. Once the rare earth is magnetized, says Rasmus Windfeld, the company's public relations officer, you wouldn't want to be standing anywhere near wearing a belt buckle or a dental bridge.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

Siemens is making 97 of the new nacelles for Germany's Gode Wind projects in the North Sea. They weigh 300 tons each. The lack of gears is expected to reduce service problems, and the giant nacelles are also designed so that when repairs are necessary, a technician can be flown out on a helicopter, instead of being sent out on a boat—a process that often involves severe seasickness. It's all part of the effort to increase efficiency and cut costs, Windfeld says. "We've cut the price of energy by 40 percent every 10 years," he boasts. "With another 40 percent drop in price by 2020, there will no longer be any reason to dig coal out of the ground."

If offshore wind is so much more expensive, why not just stick with onshore? Offshore winds are stronger and more dependable, Windfeld explains, and site opportunities are nearly unlimited. In addition, Danish law guarantees local residents the opportunity to own (and profit from) at least 20 percent of onshore turbines, an obligation that doesn't pertain to offshore farms.

On the factory floor, young Danes assemble the huge turbines, music blasting. Other buildings house giant torture devices that can shake multimillion-dollar nacelles and blades until they fall apart, trying to tease out weak spots that might fail during 25 years of storm and corrosion. Row after row of finished nacelles await shipment.

In the cafeteria, factory workers and engineers from scores of countries dine on meat and potatoes in its many variations. Siemens employs some 7,000 people in Denmark, half of them here. Vestas provides 4,000 jobs. Together, these companies dominate the world wind market, supplying 74 percent of all offshore turbines, an export market worth nearly $8.2 billion a year.

One can imagine an alternate universe in which U.S. companies had that market—but it would have to be a universe in which America had a more functional political system. Congress began support for wind energy in 1992, but only in increments of one or two years, sometimes letting it lapse altogether. Predictably, this has led to massive uncertainty and seesaw employment in the domestic wind industry. Here in Denmark, however, support has been consistent for decades. In 2012, all the major political parties agreed on the goal of freedom from fossil fuels by 2050 and provided generous subsidies to make it happen.

In the upcoming election, the Danish papers are saying, the right-wing parties are expected to win control of the government. They signed on to the 2050 goal, but are a little wobbly on the subsidies. However, Jakob Lau Holst, chief operating officer of the Danish Wind Industry Association, tells me he's not concerned. "The 2050 goal is something most parties in Parliament and an overwhelming majority of the Danish people subscribe to," he says. "We have a tradition where if you are to change a broad agreement, you have to involve all parties to change it. That's the beauty of broad agreements: They tend to be long-term, and very difficult to change."

We set sail from the port town of Grenå at 1 o'clock on a fine Saturday afternoon. The ship is the Stena Nautica, a huge ferry that plies the Kattegat between Denmark and Sweden. It's partially idle on Saturdays, however, so occasionally it picks up a few extra kroner by taking Danish daytrippers nine miles offshore to see the Anholt wind farm. Some 5,500 have done so thus far; there are about 200 on our trip, many of them elderly. Here's another way Denmark is different from the United States: The ship is so large that embarking passengers have to either climb four flights of stairs or take an elevator. No one takes the elevator.

On the voyage out, Claus Poulsen of DONG Energy, the head of operations for Anholt, leads a slideshow. He looks like Bruce Willis just before he's lured out of retirement for one more job. In Poulsen's case, that would be setting up another wind farm, as he's done in California's Tehachapi Mountains, on the South Dakota plains, and in Argentina, Japan, and India. He is all numbers: Anholt consists of 111 turbines spread over 34 square miles. Each turbine is 465 feet high with a blade diameter of 394 feet, and the wind farm has a total capacity of 400 megawatts—4 percent of the country's entire power demand. Planning began in 2010, and on September 4, 2013, Queen Margrethe II pushed another big red button and started the blades spinning. After him comes biologist Jørgen Lund Møller, who talks about the wind farm's effect on birds ("not much") and the sea creatures killed during construction: "It's very sad for the particular little fish," he says, "but in the bigger context it doesn't mean anything."

Someone says we must be getting close, so I go out on deck. We are just entering the wind farm's southern end. I am totally unprepared for the alien majesty of the enormous white towers rising in rows from the sea. The scale is hard to comprehend; the service vessels at the feet of some towers barely register. At the top of each nacelle is a bright red evacuation basket, which—in case Bruce Willis were servicing the turbine and something went wrong—could be plucked off by helicopter.

No rescues are necessary on this lovely fall day as we head for port. The passengers start drifting down to the shop to buy akvavit or brandy. Even though such goods haven't been duty-free on the ferries for 15 years, people are set in their ways.

Other notions ingrained in Danes: the expectation that a society can successfully address its problems, a willingness to pitch in, and a nonchauvinistic national pride. I linger by the railing as Anholt recedes in our wake. Watching next to me is Dorit Bazh, who is visiting from Copenhagen. Soon, she says, Denmark will have many more such wind farms. "I am very interested in it," she says. "It is the future."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club