Can Art Schools Save the Planet?

Art professors and students lit fires under the civil rights and antiwar movements. Can they do the same for environmentalism?

It was an average, not-so-sunny San Francisco day in spring 2010. Kim Anno and her art students were poking around the Internet, searching for images that conveyed environmental issues. Soon they were looking at a series of photos of Mohamed Nasheed, then the president of the Maldives, and his political cabinet, who were conducting a meeting—underwater. The idea was to draw attention to rising sea levels and the fact that their country is in real danger of being submerged.

Anno, a professor of painting and fine arts at California College of the Arts (CCA), was impressed. "We marveled at Nasheed's bravery and conceptual skill," she says. "Then we discussed what it would look like if the sea was encroaching on our country, what it would take to adapt. We looked up the statistics of how many people needed to be relocated and read that no country had yet volunteered to take the Maldives' citizens in."

"That image really kicked it over for me," Anno says, "and made me realize that I needed to do something to be part of an environmental movement that speeds things up. People's lives are at stake. I began to change my art and how I work with my students."

Anno pushed her college to join the climate summit in Durban, South Africa, in November 2011, making CCA the first art school to attend the annual conference. Anno went to all of the island-nation meetings, conceived a new project to highlight those countries' struggles, and permanently shifted the focus of her work to environmental justice. She also started to develop a degree program at her college focused on art, science, and the environment.

Despite her activist bent, Anno is careful to define herself as an artist and her work as art. "There is a distinction between art and activism," she says. "They do have overlaps, but they also have differences. Sometimes viewers discount the images of activism if they are too pat, too quickly understood. Art slows perception down and deepens the viewer's experience." That depth is key for any artwork to be able to spark a visceral response.

Artists are becoming better at delivering a strong message about climate change and painting a picture of what the world will look like if we don't take action now. Some believe that such images have a better chance than any petition of spurring action.

"Of all the things people say about what drew them to activism, only about 1 percent of the time do they say, 'Someone was handing out a flyer and I read it,'" says Steve Lambert, cofounder of the Center for Artistic Activism, a nonprofit in New York that trains artists to use art more effectively. "And yet that's the number-one way we try to get people involved in issues: to get them to sign a petition, or read a paper, or whatever. That strategy hinges on the idea that if you have the right information, you'll make the right choice. But no one who is actually involved in and committed to these issues did so because of information. It's all about these affective, emotional, lived experiences."

Lambert and and his colleague Stephen Duncombe first get artists talking about what they care about, then ask them to create a project that pairs that concern with a medium. They teach artists how to read metrics that indicate shifts in public consciousness, like increased participation and media coverage.

Meanwhile, universities across America are adding programs that pair an understanding of environmentalism with the usual skills taught to art students. They're responding to an art-world trend—galleries from Berlin's Haus der Kulturen der Welt to New York's MoMA PS1 have staged exhibits focused on environmental change in recent years—and to rising demand.

"Students have been pushing for this," Anno says. "They started coming at me with a lot of questions: 'Where is our garbage going? What's CCA doing with its stock portfolio?' I felt like if they had questions, I had to show leadership."

"I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn't say any other way—things I had no words for." —Georgia O'KeeffeIn one of Anno's pieces, an issue of National Geographic, open to the sort of landscape photo spread the magazine is known for, is submerged in water, ink swirling around it, obscuring parts of the image and highlighting others. It looks as though the ink is running off the page, as if the magazine is slowly disintegrating. It's arresting and beautiful, but what does it mean?

Anno, like her compatriots in the emergent eco-art scene, doesn't create the sort of obvious, earnest pieces we've come to associate with environmental art. There's no call to action stitched in hemp or polar bears made out of trash, nor a limitation to earth tones.

"My aim is subversive," Anno says. "I want people who don't necessarily define themselves as environmentalists to stop and think. I want my pieces to grab the audience and shake them. What does this mean? You figure it out."

She likes to play with elements traditionally thought of as being part of the environmental movement. "National Geographic is perfect," she says, "because it's had such a complicated history. It does a good job in some respects of showing these beautiful places that need protecting, but it's also part of the history of colonialism. Its coverage for a long time had this way of distancing the West from the developing world by romanticizing these exotic locations. So I'm using irony there. I want the viewer to do some work and figure out why this woman would plunge a National Geographic underwater and make it look like it's exploding."

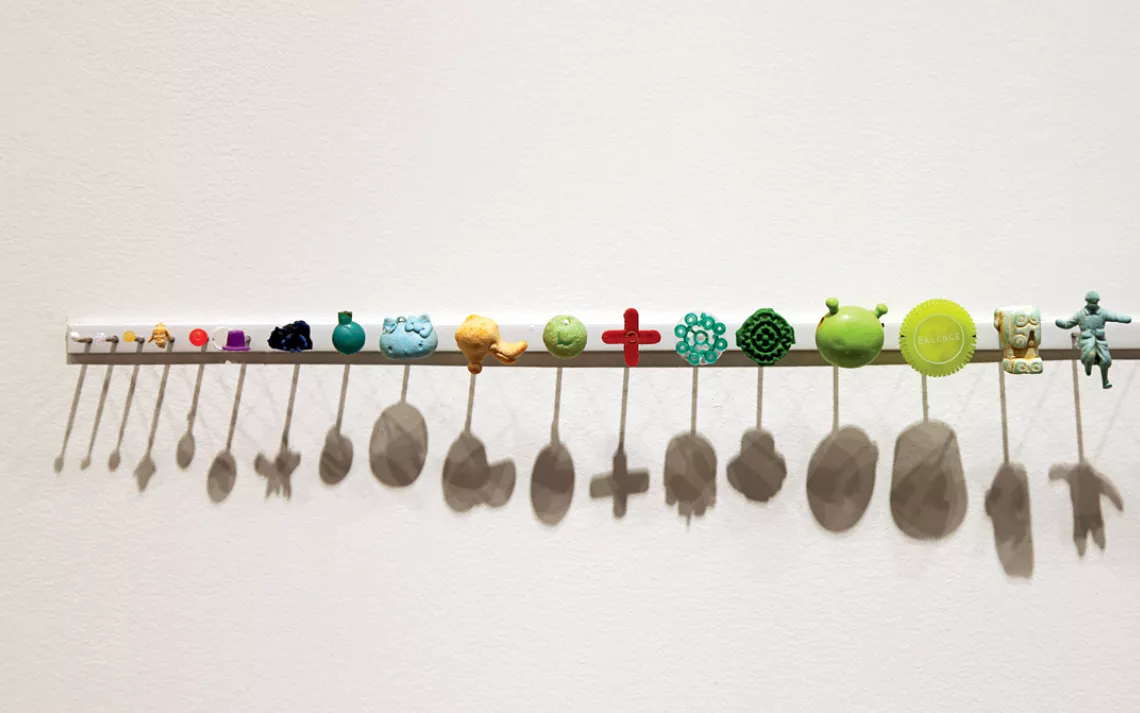

With his elaborate curio cabinets filled with the detritus of man-versus-nature interactions, artist Mark Dion, who mentors students at Columbia University and last year was a fellow in Brown University's Department of Humanities, is also big on encouraging viewers to think for themselves. He says environmental art is increasingly effective because more artists are taking a complex, layered approach. "These works," he says, "demand more from the viewer and are thus able to penetrate deeper, mean more, and signify powerfully."

Very little is known about what exactly humans respond to in art, or why what moves one person leaves another cold. Neuroscientists point to the brain's medial orbitofrontal cortex—part of the pain-and-pleasure center—as the source of our emotional response to visual art.

While there's no template for making art that elicits a strong response, today's eco-artists believe it's crucial to create pieces that bear witness to the damage humans are inflicting on the planet.

"At one point, I became convinced that environmental issues were really information problems," Dion has written. "I believed that if people knew the damage their way of life caused to the natural world, they would change. . . . My early work tended to be quite informational and didactic since I was literally attempting a kind of sculptural documentary practice." After a while, it became apparent to Dion that knowledge wasn't the problem: "The main issues were questions of political will, ideology, capitalism, and psychology."

That realization has made Dion's recent works more pessimistic and melancholy. "Dark conclusions and complex positions that end in ambivalence are difficult to articulate," he writes. "You cannot express these sentiments in politics, in activism, perhaps even not in journalism. Art is an excellent place to express complexity, paradox, uncertainty, ambivalence and hopelessness. The role of the artist as witness can be as valuable as the artist as catalyst."

"Truth and beauty can still win battles. We need more art, more passion, more wit in defense of the Earth." —David BrowerThe history of art as a lever of social change is rich with examples. In New York City, in 1935, the NAACP organized an exhibition of art about lynching. Raising awareness of the practice may have been what led to the prosecution of lynching cases throughout the country. Meanwhile, Picasso was busy painting Guernica, which made the world aware of the Spanish Civil War at a time when few other modes of communication had such reach. More recently, Cindy Sherman, Judy Chicago, and the Guerrilla Girls have used photography, collage, and painting to empower women to question prescribed gender roles. In short, art has been vital to communicating the need for social change. The need for environmental action? So far, not so much.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

In part, that's because it's a relatively new genre. Nature photography has been around since the invention of the camera, but fine art with an environmentalist slant began appearing in galleries only over the past few decades. The roots of today's eco-art movement were planted in the late 1970s but lacked the groundswell of discussion common to other socially based art movements. Early environmental artists tended to work alone and focus on a particular issue—a river in their hometown, say, or a landfill up the road.

In recent years, that has started to change. The discipline is maturing, becoming more of a discernible movement, and there are enough good works that many galleries are staging exhibits focused solely on environmental issues. Artists are also getting better at partnering with each other, with community organizers, and with scientists.

Dion, in particular, places emphasis on collaboration. When this reporter reached him in New York, he was on his way to meet fellow artist Alexis Rockman at the American Museum of Natural History so that they could spend time together in the archives. Rockman is the artist behind the dazzling Life of Pi visuals, but a vast majority of his works, which he describes as "psychedelic natural history," are created with a specific conservation aim in mind. He's in the process of producing a series that looks at what human and geologic activities have done to the Great Lakes. In addition to outings to the archives, Dion travels with other artists—and sometimes scientists—to inspiring wild places.

Dion quotes his friend, the conservationist Carl Safina: "Science does a pretty good job of telling us what the world is but not what to think or feel about it. That is the job of art." He adds his own words too: "Art and science also share the same enemies: prejudice and ignorance. If there is one thing that ignorant, fundamentalist, right-wing jerks hate more than science, it is art."

Some environmental artists venture so far into the realm of ecology that their art doubles as restoration work. Daniel McCormick and Mary O'Brien build sculptures in waterways to create habitat for displaced species—salmon in the Pacific Northwest and oysters in California's Bay Area. Jason deCaires Taylor, an English sculptor, travels the world making underwater pieces that turn into artificial coral reefs. Mel Chin has been working since 1991 with Rufus Chaney, a research agronomist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, on Revival Field, a project on a Superfund site in St. Paul, Minnesota. It sits on a plot of land divided into four quadrants with an X in the middle. The plants in each quadrant accumulate heavy metals in their leaves, gradually cleaning the land. While a garden on a landfill may not seem like art, Chin speaks of carving pollution out of the earth as Michelangelo carved figures out of marble.

The public might not immediately buy into these forms of hard-core ecological art, but gallery artists talk about these guys in reverent tones. Dion, something of an art star in his own right, describes artists doing on-the-ground ecological work as "raising the bar for everyone."

"Art is not what you see, but what you make others see." —Edgar DegasMounting evidence suggests that in the coming decades, environmental art will have the same sort of disruptive impact that social and political art have had. As more artists do this type of work and more galleries become interested in it, there's a corresponding rise of support for environmental art programs in universities, and an exploding demand for such programs. Every art professor interviewed for this piece said the same thing: Students want more classes focused on the intersection of art, the environment, and social action. Foundations and institutions are now offering grants for projects that fall into that overlap.

At a time when conversations about climate problems often center on people's belief systems and emotions, we need compelling environmental art more than ever. "Art can kind of curl around a viewer and enter their being through a different route," says Julie Anand, an artist who teaches a class at Arizona State University called Systems, Ecology, Art. "You've already had an experience before you realize it, and then there's time for processing and questioning and reevaluating your experience later."

Still, Dion cautions that art is only one weapon in the vast arsenal that's needed to protect the world from environmental disaster. "It works best when in collaboration with other forms of culture," he says. "When viewers are getting the same sentiment from literature, news, neighbors, the broader culture, they're more likely to take things seriously."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club