Repower LA

Los Angeles is kicking coal, but it isn't easy. This labor-enviro coalition is helping low-income Angelenos make the transition—through energy efficiency and jobs.

The late-June weekend heat wave comes on as predicted. By 10 a.m., it's 90°F in a South Los Angeles parking lot where scores of local residents have gathered, lured by community leaders and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP). Over the hum of the crowd, speakers take the stage for this Green the Block workshop: community organizers, environmentalists, labor union leaders, and local politicians, all talking about the changing climate, the sputtering economy, and the need to use less energy. It's important stuff, but not particularly riveting. Meanwhile, it keeps getting hotter. By the time Ron Nichols, the utility's general manager, takes the stage, the sun has chased people under canopies at either side of the lot, and the chairs in front of him are almost empty.

Nichols, a tall man with a dust of white hair and an aquiline profile, seems eager to connect with the audience. At first, the conversation and laughter threaten to drown out his message about energy waste and carbon dioxide emissions. But then he hits a riff that resonates, about how the utility's energy efficiency program also includes free home retrofits and training for new electrical workers. "More than anything else, what we're doing is putting jobs where we need them the most," he says, smiling broadly and picking up the pace. "And with our home energy improvement program, we're going to save you all money!"

Like the sax player in the back of the band who goes unnoticed until his solo, Nichols gets a robust round of applause, even a few whoops of appreciation. When he walks off the stage, several local matrons in flowery dresses and hats walk over to shake his hand.

The spectacle of the leader of the nation's largest municipal utility working hard to engage the attention and respect of constituents in downtrodden neighborhoods is something new for the DWP. Founded in 1902, the utility doesn't exactly have community outreach in its DNA. Its first superintendent, a dictatorial engineer named William Mulholland, secretly dumped huge amounts of city water into sewers to scare the public into supporting his effort to grab water rights to the Owens River. That attitude prevailed for most of the department's history.

In the past few years, however, the tone has begun to change. These days, the DWP is actively enlisting residents and businesses in its efforts to move the city off coal-fired electricity and to reduce its dependence on imported water. It's a new day.

How did an ossified utility come to link arms with activists and environmentalists for climate and economic justice? The transformation began nine years ago, when the Los Angeles City Council mandated that the utility, which relied on out-of-state coal for half of its electricity, acquire 20 percent of its power from renewable sources by 2017 (a goal later moved up to 2010). To fund the transition, the DWP proposed a 5.7 percent rate hike, which then-mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and environmental groups, including the Sierra Club and the Coalition for Clean Air, supported. The Los Angeles City Council, however, unanimously decided that it was too steep. The conflict turned so bitter that at one point the DWP threatened to withhold from the city's general fund $73 million of the roughly $200 million the utility brings in each year—an amount equal to the annual salaries of 1,000 city employees.

When Nichols took over in January 2011, the utility had burned through four general managers in three years. Even though the controversial rate increase had yet to go through, the American Customer Satisfaction Index still ranked the DWP as the 13th most hated company in America that year.

The debacle marked the modern nadir in the utility's public esteem, but it created an opening for a coalition of environmentalists, labor unions, and economic justice activists called RePower LA, which came together in 2010 as a project of the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, or LAANE. "We came to them with a very positive vision and big ideas," says Jessica Goodheart, RePower LA's director. "Our message was, if you're going to raise people's rates, you need to commit to energy efficiency programs that will keep their bills down. And you need to help the customers who have been struggling the most, including people on fixed incomes."

The message resonated with environmental leaders, who had come to understand that talking about a transition to clean energy also necessitated talking about jobs. "We knew back then that it was insufficient to just say, 'Let's get rid of coal,'" says Evan Gillespie, associate regional campaign director for the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal Campaign. "We had to have a set of replacement solutions that we could hold up. LAANE's values are core to the Club: equity, good jobs, clean energy."

The search for a solution led LAANE to join forces with Brian D'Arcy, head of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 18, who had spent years working to address unemployment in low-income communities as well as the accelerating attrition problem among electrical workers. Forty percent of the DWP's union employees are at or near retirement age, and their jobs can't be easily filled.

Shawn McCloud, Local 18's assistant business manager, explains that the electrical trade requires a lengthy apprenticeship. But as schools cut shop classes, teenagers aren't emerging from high school with any foundation in electricity. "We didn't have a source of new workers to draw from," McCloud says. "We needed to go into the community and find them."

The solution was the Utility Pre-Craft Training program, a collaboration between the union and the utility that took five years to develop. Worker-trainees must live in Los Angeles County and possess a driver's license and a Social Security card. Other than that, McCloud says, "if you have a willingness in your heart to learn, we can train you."

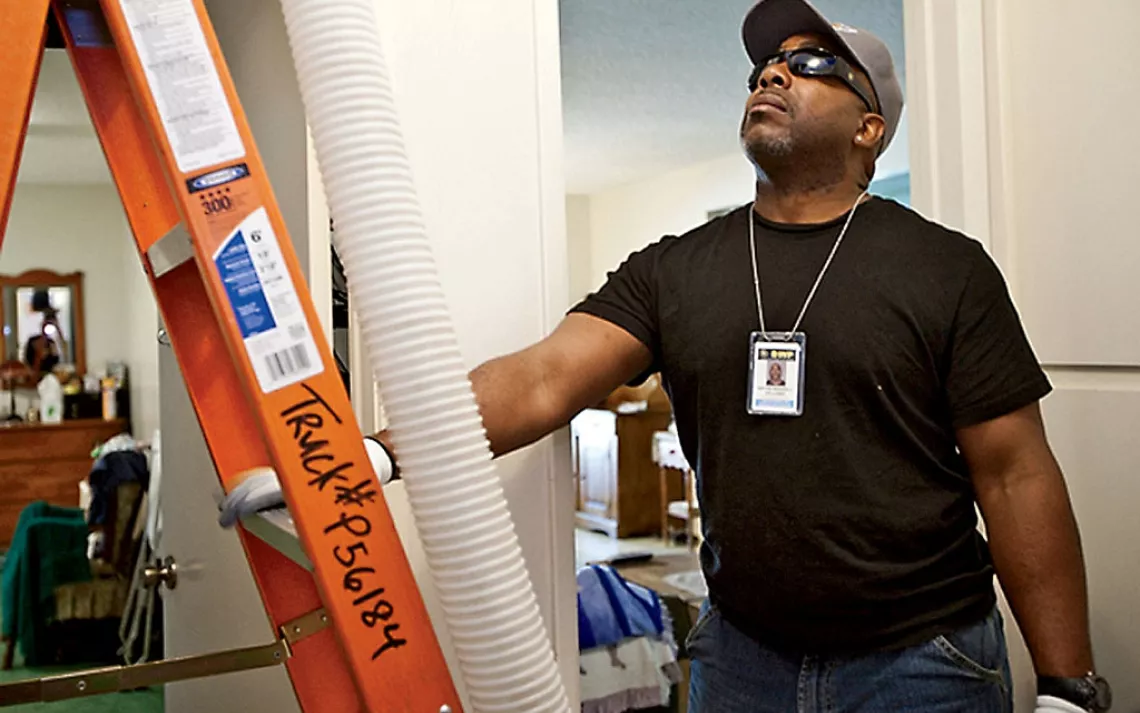

Worker-trainees, who range from teens to those in their 50s, earn $16 an hour plus benefits and go to work immediately, conducting audits to find where energy is being wasted in homes and local businesses. They also help weatherize buildings and install energy- and water-saving components, like motion sensors and low-flow toilets. At the same time, they train for potential careers with the utility.

The program is financed by a $9 million federal grant under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (a.k.a. the federal stimulus program). In a separate program, households beneath a certain income threshold can also have their power-sucking refrigerators replaced with new energy efficient models. The work is done by trainees drawn from low-income areas of Los Angeles County, each accompanied by a journey-level technician.

To get the word out about all of these benefits, McCloud says, executives at the utility, environmentalists, and labor leaders have had to go into the community "united as one." That is, she notes delicately, "something different from what we've seen." Relations between the utility, unions, and new mayor Eric Garcetti have been rocky. But, says Jonathan Parfrey, executive director of the nonprofit Climate Resolve and until recently a DWP commissioner, "away from the headlines, there has been and will continue to be cooperation." RePower LA, he says, "shows the way forward for a better ongoing relationship among everyone involved."

"Does anything come for free?" Kokayi Kwa Jitahidi shouts to a cluster of people who are gathered at the Green the Block event. It's hard to get people worked up about weather stripping in the attic, but Kwa Jitahidi turns energy efficiency into a matter of basic justice.

"Does anything come without a struggle, without a movement?"

"No!" the crowd yells back.

"We want to make sure you understand that," he says. "There are people who believe that these services shouldn't be available to people like us. There are people who don't even believe in global warming. We want to make sure you know how much work it took to get these programs, because we're going to have a lot more work to do."

Kwa Jitahidi, 33, grew up in Long Beach, where diesel trucks and oil refineries chuff soot and exhaust. When he was little, so many of his friends had respiratory inhalers that he told his mother he wanted one too, just to fit in. When he was 10, he saw the body of a neighbor his age being taken out of his apartment on a stretcher. "He had an asthma attack, collapsed, and died," he remembers.

"I always felt very solid in my environmental identity, even though I didn't associate myself with mainstream environmental organizations," he continues. RePower LA fused his social justice goals with his environmental ones: "It's a campaign that's very consistent with the struggles that I've seen."

If casting energy efficiency in such dramatic terms seems overheated, consider that 38 percent of Angelenos live in "real poverty," defined as twice the federal poverty line of $11,000 a year. The unemployment rate in the neighborhood surrounding this parking lot has been close to 25 percent for years. Forget the economic downturn: People here never enjoyed the bubble that came before. A lower electricity bill may mean the difference between eating and going hungry; it may mean that kids can have lights on in the evening instead of doing homework by flashlight.

Energy efficiency may not be the glittery new green technology that will disrupt the energy market and painlessly solve climate change. The continued investment by the DWP in auditing and retrofitting buildings and in replacing old appliances may raise rates, as may the closing of fossil fuel plants and the construction of renewable infrastructure.

"People say, that's a big bump-up on rates for the amount of [dirty] energy you're avoiding," Ron Nichols says. "But there's a whole spectrum of job creation that comes out of energy efficiency. You need everything from someone to caulk windows and put in insulation to architects, designers, and finance people. You need lower-skills jobs and higher-skills jobs." And some of them you need to cultivate.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club