Bison and Boundaries

Can Yellowstone's signature mammal and the region's ranchers just get along?

Zack Waterman and I are postholing through the snow when I notice the unmistakable oversize tracks of a grizzly. Quickly, we amp up our hollers of "HEEEEYYYYYYYY, BEAR!"

We're headed into Yellowstone National Park's once-remote Pelican Valley, a crescent-shaped dale studded with thermal features. More than a century ago, 23 wild bison found sanctuary there after surviving the slaughter that decimated the 50 million Plains bison that once stretched across the country. Standing in a grove of lodgepoles, Waterman and I fall quiet and listen to the wind shaking the pines. We imagine what it might have felt like to stumble upon the last of North America's largest mammal.

"It's pretty profound that where we found the last wild buffalo is also where we have the opportunity to preserve the species," says Waterman, who at the time of our hike was an organizer for the Sierra Club's Greater Yellowstone campaign and is now director of the Club's Idaho Chapter.

While bison are found across the United States, most of them are restricted to bison ranches. (Bison bison--their scientific name--are commonly called American buffalo, but their large shoulder hump and massive head distinguish them from true buffalo.) Only five states with bison populations allow them to move as free-roaming wildlife, like elk and deer. Yellowstone's 3,700 bison have retained a genetic line free of cattle genes. They are our last wild bison.

But "free to roam" doesn't mean "free of risk." Since 1985, 7,189 Yellowstone National Park bison that have stepped across park boundaries have been killed (or "lethally removed," as the lingo goes) by federal and state agencies in an effort to placate local ranchers' fears that bison will infect their livestock with the disease brucellosis (which has been eradicated in livestock but still exists in bison and elk), damage property, and outcompete their cattle for grass.

Recent developments--including large conservation easements and fencing campaigns, new scientific evidence that counters fears of disease transmission, agreements with tribal leaders, and a plan that may open a large new swath of public land to bison year-round--have many bison advocates optimistic that one key state, Montana, may be on the verge of unprecedented compromise. The battle to protect wild bison won't be over--Yellowstone bison are still shot dead on arrival in Idaho, and their movements are strictly regulated in Wyoming--but it's a significant step toward reclaiming a bit more of the "wild" in wildlife.

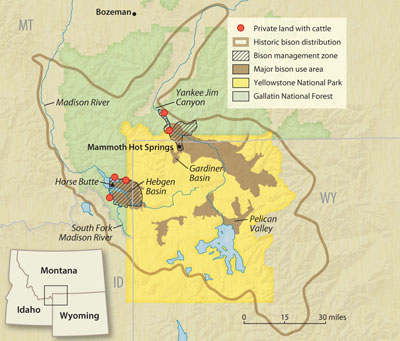

Our journey to the Pelican Valley, in Wyoming, provides an informal tour of Yellowstone bison management history and the dichotomy between wildlife and livestock. About 50 miles up the road at Mammoth Hot Springs, concrete remnants of old pens can still be found from the days when Yellowstone National Park kept bison on display for visitors, as in a zoo. Just outside the park's massive stone entrance arch, we pass a capture pen where bison that have wandered out of the de facto animal preserve are held before getting shipped off to slaughterhouses if they test positive for brucellosis antibodies.

At the Yellowstone border (the end of a nondescript dirt road), we survey an expanded zone outside the park where bison are tolerated--and for the first time in nearly a decade, tribal hunters were recently able to exercise their treaty rights to hunt bison exiting the park. (Recent court decisions have allowed bison, long a part of Native culture, to be transferred to reservations in northeast Montana.)

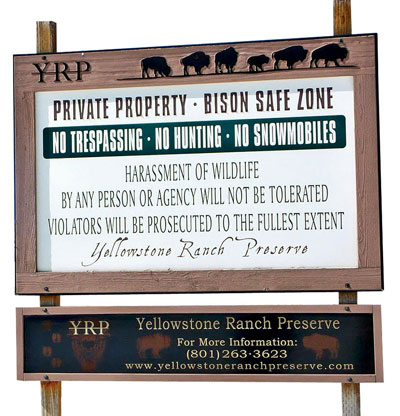

Next, we detour across the road to the Yellowstone Basin Inn, where a BISON SAFE ZONE sign hangs in the window. Newly built pole-and-rail fences protect trees, backyards, and gardens from free-roaming bison.

"The lodge owners say the only time there is a problem is when the Montana Department of Livestock shows up," Waterman explains. "For a lot of politicians and folks who testify in support of keeping bison out of Montana, one of the biggest arguments is private property rights. But the irony is that the department, which represents Montana ranchers, can enter private property without a landowner's consent."

We pass a large conservation easement north of the park that in 2011 nearly quadrupled the amount of space available to bison in the Gardiner Basin to 70,000 acres. Next we come upon the holding pens leased by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services for grazing studies and experiments with GonaCon, an immunocontraceptive used to sterilize bison with brucellosis.

About 18 miles outside the park boundary, we rattle over a cattle guard marking the mouth of Yankee Jim Canyon, in Gallatin National Forest. I don't give it a second thought until Waterman explains that the cattle guard, installed in 2011, stops bison from moving farther north. And therein lies the heart of the controversy.

At the end of each winter, after months battling harsh conditions, Yellowstone bison descend en masse from the park into the Gardiner and Hebgen Basins in search of emerging plants and comfortable calving sites. Lands in the Yellowstone region are divided into three distinct zones: Zone I is where bison are tolerated year-round--that is, anywhere within the park. Bison are tolerated in Zone II November through May 15, at which point they are "hazed"--herded by bison wranglers on horseback and sometimes helicopters--back into the park. Farther out, Zone III is off-limits to bison year-round. Depending on the time of year, bison found in Zone III are either hazed into the park or killed. To accommodate a growing bison population, the Sierra Club and other groups have been working to expand Zone I to include two large swaths of U.S. Forest Service land--closer than ever to cattle and ranchers.

Inside the main cabin at Buffalo Field Campaign's headquarters in the Hebgen Basin, an altar displays bison talismans, and buffalo-themed art and civil disobedience stickers decorate the walls. The campaign's volunteers have been zealously documenting bison management efforts since the winter of 1996-97, when Montana's Department of Livestock killed approximately 1,100 Yellowstone bison as they exited the park.

I made my first trip up to the Buffalo Field Campaign's headquarters while snow still blanketed the ground. Stephany Seay, a 10-year veteran of the campaign, showed me the lay of the land. While some ranchers are rabidly anti-bison, several of the Hebgen Basin's ranchers and even residential neighborhoods welcome the bison and other animals that congregate in their front yards like oversize garden gnomes. Prominent neon NO TRESPASSING signs hang in many front windows.

With the May 15 deadline a week away, land management agencies have been staging the bison on Horse Butte, the dividing line between safety and slaughter, for one final haze from Zone II back into the park. Unruly animals that resist will be shot. That's good for land managers, but not for a genome that some say is already at risk, considering the bison management plan's target population of 3,000 in the Yellowstone region--a compromise between land agencies and private interests. It doesn't account for future uncertainties like climate change and disease. The Buffalo Field Campaign claims that 5,000 mature adults are needed to maintain a viable population.

At 8:44 a.m., the campaign's volunteer crews perk up as a Gallatin County sheriff vehicle passes with a Department of Livestock trailer in tow. "The whole shebang is moving out," Cindy Rosin, an art teacher from Queens, New York, with magenta braids, says over the radio.

Two volunteers and I pull our bikes from a truck bed and ride two miles to a turnout overlooking the South Fork of the Madison River, where we spot a herd moving through private land belonging to local rancher Pat Povah. We intersect the haze and spend the next three hours trailing 93 bison, five federal and state riders, and a Forest Service law enforcement vehicle. There's a romantic cowboy feel to it. Except that this isn't a cattle drive; these are wild animals being pushed off migratory land back into what has effectively become a preserve for their species.

Like many stock growers, rancher Povah feels there wasn't a problem until Yellowstone changed its management strategy in the 1980s, allowing herd numbers to fluctuate more naturally. As numbers rose, bison began leaving the park on roads groomed for snowmobiles and snowcoaches and through forests opened up by wildfires in 1989.

"It's the park's responsibility to manage the numbers before they leave the park, and that's not happening," Povah says. "The whole burden is dumped on the surrounding states." He cites the large materials and labor costs associated with repairing fencing, trampled rangeland, and testing cattle for brucellosis.

Since 1934, brucellosis has been listed as a federally controlled disease--with nationwide eradication being the goal. But so far, bison have infected cattle with brucellosis only once, and that was in a lab.

The issue became compelling with the release of a 2012 study by the Wildlife Conservation Society's Dr. Keith Aune on the persistence of brucellosis bacteria in the soil. Aune's study showed that the bacteria linger for only two weeks under the vast majority of conditions, and in any event do not last beyond June 10. Holding out for a few weeks longer could negate the necessity of a May 15 hazing date. Regardless, Montana Department of Livestock director Christian MacKay says that the risk of infection, however slight, still persists. "If you want to have zero risk for disease transmission between livestock and wildlife, forget it," Aune says. "The truth is [ranchers] don't have zero risk anywhere in the industry."

Aune's research is thrusting the true conflict in the bison debate into the spotlight: Bison opposition isn't just about brucellosis; it's also about how bison impact grazing lands.

"Bison are hard to live with because of their size and their behavior," explains wildlife biologist Rick Wallen, team leader for the Yellowstone's Bison Ecology and Management Program. "Deer and elk are willing to hide in the mountains if they have to. Bison select habitat along river and stream corridors. But that's where the humans want to be."

In July, Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and the state's Department of Livestock released the Year-Round Habitat for Yellowstone Bison Environmental Assessment, which includes six options. Come next spring, bison could be roaming free year-round on as many as 421,821 acres adjoining Yellowstone. Or nothing could change, and existing zones could remain in place. A decision is expected by early 2014.

By mid-afternoon, my companions and I have curved back to the Madison River. The herd has traveled just six miles, but that's a lot for newborn calves that have to cross terrain littered with dead trees. As the animals approach the stream, I hear a shout from the trees. "How does it feel to kill babies?" I look to Jeremy for an explanation. "Oh, that's Justine," he says. "Yesterday one of the rangers got sick of it and yelled back, 'Talk to your congressman. I have nothing to do with it.'"

The herd steps into the river and swims in--a brown mass moving across the current, mothers swimming upstream of their young. I feel like I've stepped back in time. Except that waiting on the sidelines is an assortment of horse trailers and law enforcement rigs.

Bison management is caught in a complicated web of state, tribal, and federal agencies, each with its own agenda. The next day I head to Bozeman for a meeting of the Interagency Bison Management Plan working group responsible for determining the mammal's fate. As participants introduce themselves at the table, Ron Trahan, councilman of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, says, "I don't know if we're sitting on the right side of the room."

"There is no side," the moderator says. "That's the point."

It doesn't always play out that way. It wasn't until 2009, nine years after the initial Interagency Bison Management Plan was produced, that tribal interests were invited to the table, despite their deep connection to bison. And since the working group operates by consensus, in effect the Department of Livestock must agree with all decisions.

Yellowstone biologist Wallen's quiet voice sounds over the microphone. If the bison were given just another two weeks beyond the May 15 deadline, he says, they'd move back into the park on their own following the "green up."

"I don't want to affect the permittees' ability for grazing," responds Department of Livestock director MacKay, explaining how hay purchases for those additional two weeks could create undue burden on his constituents.

One rancher is upset over the eight instances when bison had to be moved away from his cattle. "Put an eff'n fence in," mutters an un-uniformed ranger sitting near me.

She's got a point. Montana is a "fence out" state, which means that it's the landowner's responsibility to fence out bothersome animals. When I ask Povah about it, he says that bison can tear through barbed wire and jump any fence shorter than eight feet high. Wooden rail fences are expensive and at that height would affect the movement patterns of all other wildlife, he says. But each year the Interagency Bison Management Plan spends some $3 million on hazing bison back into Yellowstone. Perhaps that kind of money might fund the R&D necessary for constructing a wildlife-friendly bison fence.

Two rows in front of me sits Becky Weed, a sheep rancher and former Montana Board of Livestock member, clicking away at her knitting. Weed, who along with Waterman participated in the Citizens' Working Group, which advised on the management plan, is hopeful that change is coming despite the glacial pace. While anti-bison advocates like Montana senator John Brenden (who recently called bison "vermin . . . in need of extermination") and the Montana legislature (which brought 14 anti-bison bills to the floor this year) might give the impression that it's the old rerun of environmentalists against ranchers, Weed says that the reality is more complicated. "Big trade organizations represent one point of view," she says, "but at the grassroots level, it's a lot messier."

Weed says her ranching peers ought to direct their attention to issues bigger than bison. "When you look at the changes facing ranchers--drought, climate change, changing consumer preferences, increasing concerns about where meat comes from--there are unfathomable implications. Bison are an easy target," she says. "They aren't a threat to agriculture, but they are a threat to agriculture as it's currently practiced."

Driving back to my home in Idaho, I think about how bison once roamed the entire 200-mile distance. I'm reminded of the cross-country ski trip I took around Horse Butte after my first visit with the Buffalo Field Campaign's Seay. Racing against the setting sun, I was distracted. I raised my head just in time to greet three large bison in my path.

We watched each other for a while, as a band of lodgepoles cast a dark shadow across the snow. I wanted to welcome them, to somehow tell them to cross the line, to join me in the sun and venture to the far side of Horse Butte, where I'd just been. No success. But I sense that we might be getting closer to the day when North America's largest mammal and its most impactful one can coexist.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Our Wild America campaign.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club