At first glance, the outcome seems contradictory: why would more stringent automobile emissions standards from the EPA threaten an increase in air pollution for low-income communities in Detroit? Something, surely, is amiss. But an inimical and unexpected pattern lurks, complicating the legacy of our country’s brightest environmental moments. Often, these intertwined histories of disaster are silenced, swept under the rug as climate victories assume the pedestal. No one can doubt that the EPA has taken on the task of freshening up America’s air with the best of intentions. The outcome, however, like all environmentally involved outcomes before it, is more convoluted.

Historians tend to credit Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, with touching off the environmental movement. The book shed light on the environmental dilemmas of the day: pesticides, toxic waste, and nuclear fallout. These blights required the public to envision new and different mediums of exposure. The physics of harm had, until then, been direct and simple: the massive carnage of the World Wars had been wreaked by guns and bombs; disease was airborne, but illness was becoming increasingly preventable as modern medicine emerged in the United States. But Carson and contemporaries broadcast new agents of toxic violence, which travelled, invisible and undetectable, through the air, water, and soil.

Catching and controlling these toxins was of the utmost importance to environmentalists, mostly white and middle- to upper-class in this first wave of the movement. They were the ones with the money, leisure time, and education to properly tackle the issue. The real matter was how to dispose of these chemical demons, where to place these newfound undesirables. The rallying cry was clear: anywhere but here.

Toxic waste, once removed from general circulation, demanded a final resting place. Where better for companies to drop it than in the midst of low-income communities of color, which had little to no familiarity with political efficacy, were less organized, and possessed few resources with which to wage the fight for fair and equal treatment?

Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, a groundbreaking study undertaken by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice and published in 1987, found race to be the best indicator of close proximity to toxic waste and hazardous materials, a better predictor than socio-economic status or region. A 2007 follow-up to that study reported the same, and also noted that communities of color experience unequal protection from the government in the face of risk: white communities living near toxic waste sites see faster action, more effective cleanup, and tougher repercussions for polluters than their black and Latino counterparts.

For corporations, this tactic isn’t just about path of least resistance; environmental racism is a strategy. Placing refineries and toxic waste sites in poor communities of color is proven to save companies money on legal fees, buyouts, and cleanup costs.

The story of DDT follows a similar narrative. Its use was banned in the United States ten years after Silent Spring hit the shelves – a step in the right direction, to be sure. But although the pesticides that replaced it were less persistent, their shorter half-lives were more insidious. Consequences of pesticide use became narrower and more intensified. They played out on the health of migrant farm workers tasked with spraying the chemicals onto crops. This labor force lacked money, education, and in many cases the citizenship necessary for legal standing. By the time food reached the dinner tables of the well-off suburbanites who’d launched the crusade against DDT, potential for harm had dwindled to nothing. The noblest of efforts served to reposition the density of consequences. The intent was not malicious, but the impact was.

What all this points to is a truth difficult to stomach: the environmentalism of the 60’s and 70’s, at least its most mainstream components, resulted in the environmental racism of today. This isn’t to say that the movement was unproductive; it prompted legislative reform, the creation of the EPA, and a national awareness of a realm in need of protection: the “environment.” But as Robert Bullard, often regarded as the “father of environmental justice,” notes in his book Dumping in Dixie, the movement became less about mass mobilization and more about utilizing political structures and class-action lawsuits for forward momentum, and underrepresented minority groups were further cut off from access. We are bound to a long-ignored casualty. For those who were legally and financially defenseless, exposure to toxins got worse, not better, in the face of growing awareness.

This same dynamic is mirrored today in southwest Detroit. The Marathon Petroleum Corporation is responding to more assertive sulfur dioxide emissions standards under the EPA’s Tier 3 program, which goes into effect in 2017. Sulfur dioxide is a known perpetrator of nosebleeds, asthma, and cardiovascular problems. The company proposes removing more sulfur from its oil at the Detroit refinery before the gasoline is pumped into vehicles. For most Americans, this guarantees better air quality.

But all this extracted sulfur must be released somewhere. In this case, it’s into Detroit’s air and water. Southwest Detroit residents find themselves within a “sacrifice zone,” an Orwellian term originally coined in reference to the Cold War, and given careful treatment in the context of environmental justice in Steve Lerner’s book, Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States. As Lerner puts it,

"Low-income and minority populations, living adjacent to heavy industry and military bases, are required to make disproportionate health and economic sacrifices that more affluent people can avoid. To my mind, this pattern of unequal exposures constitutes a form of environmental racism that is being played out on a large scale across the nation.”

Andrew Sarpolis, a Michigan-based organizer with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign, says residents of southwest Detroit’s 48217, the state’s most polluted zip code, are well aware of their placement within a sacrifice zone. “Folks feel they’re not being heard, that their neighborhood is just used as a means of dumping. The richer, whiter suburbs are exploiting them.” Those with stock in the oil refinery aren’t forced to endure the pollution it generates. “The industry is there,” Sarpolis emphasizes, “But those who own and regulate the factories don’t live in the area.”

Rhonda Anderson has been a mobilizing force behind community activism for years. A lifelong resident of southwest Detroit, her environmental justice work started long before she joined the Beyond Coal Campaign. In 2007, Anderson was one of the activists who succeeded in getting Jennifer Granholm to sign an EJ executive order. She now works with her community as a Sierra Club Environmental Justice organizer. She won the Sierra Club’s Virginia Ferguson Award in 2013, and the Mike McCloskey Award in 2015, both for her work in the 48217.

In 2012, Anderson was involved in negotiations for the Oakwood Heights Property Purchase Program. The Marathon refinery was expanding, preparing to process heavier crude oil, partially in anticipation of the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline, which was ultimately blocked by President Obama last year. Marathon offered a buyout to residents of Oakwood Heights, a predominantly white neighborhood in the 48217. Meanwhile, neighboring Boynton, which is predominantly black, was offered no buyout.

“I was part of that,” Anderson says of the Oakwood Heights buyout. “We suggested that action immediately.” Anderson is not resentful, and is careful not to pinpoint race as the motive for one neighborhood getting a buyout while the other did not. “The new refinery was being built literally on top of Oakwood Heights.” But the reason these communities are divided in that way, so that a predominantly white neighborhood can be neatly cleared while a predominantly black one across the street continues to suffer through debilitating pollution – “That’s a legacy of racial segregation.”

“It’s unusual,” Anderson concedes, discussing the joint efforts of Boynton and Oakwood Heights, “But the white and black communities really did work together. Oakwood Heights had the chance to escape, and they did.”

“My heart is in environmental justice,” admits Anderson. This is anything but a straightforward pursuit in her hometown, where companies and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) fog up details around the hard science of pollution in order to keep residents helpless and subdued, even as they find themselves with dramatically above-average rates of severe illness.

Theresa Landrum is a colleague of Anderson’s and a native of the 48217, the daughter of a one-time Marathon employee, a journalist by trade, and a cancer survivor. She lost both parents to cancer, long before her own diagnosis in 2007.

“It’s common to have your entire family taken out by cancer. We’ve had a funeral every day this week for someone who’s died of it,” Landrum says. The picture she paints is one of a carcinogenic warzone. “Often, cause of death is said to be blood clots and pneumonia – but I think these things are really symptoms of the cancer. We know we’re ill, but we’re not professionals. We need specialized doctors, a health study, and cancer mapping of the area.” At the time of this statement, Landrum was in bed with the flu, finally able to sit up again after a day of being too weak to do so. She knows the sinusitis she experiences is a result of her polluted surroundings.

In 2013, Rhonda Anderson spearheaded a program called the “Bucket Brigade,” which trained residents in the Boynton and Oakwood Heights neighborhoods to collect air quality samples from their own homes (a stellar example of citizen science, a growing movement which allows locals of an area to collect their own data on toxicity when corporate and government monitors flounder). Adrian Crawford, an Oakwood Heights native who refused to move when Marathon offered a buyout, took air quality samples from her basement and sent them away for lab analysis. Soon enough, the lab was contacting her, reporting levels of ethane and ethyl benzene so unsafe they urged her to evacuate her home immediately.

“We contacted the MDEQ and they did nothing,” Anderson remembers. No action was taken until Channel 7 News caught on and attracted the attention of the EPA. “The EPA came in and did their tests, and their results were consistent with the lab’s findings. Even then, when the MDEQ came in to do the same tests, they claimed there were no chemicals.” When trying to explain the difference between the EPA’s findings and their own, the MDEQ speculated they may have used the wrong equipment.

“But,” Anderson asks, “How many times have they used the wrong equipment? The explosion at Marathon,” – Anderson is referring to the explosion of a diesel tank at the Detroit refinery in 2013, which resulted in an order for a two-hour evacuation – “when they were testing the air after that, were they using the wrong equipment then?” Anderson chalks it up to deception, an attempt to shroud the danger the community faces every day.

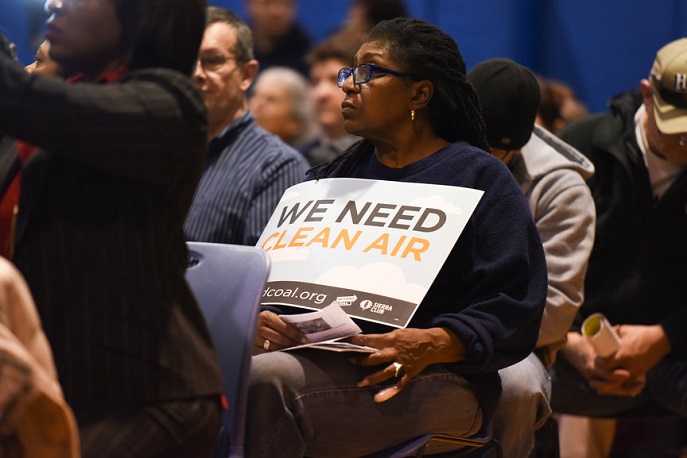

Activist Vicki Dobbins shows her support for the Beyond Coal Campaign and clean air at last night's hearing.

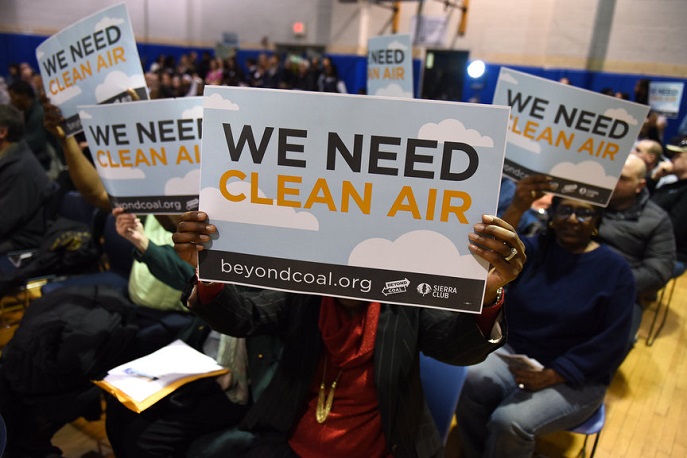

The effort underway now, to block Marathon from relaxing its emission standards, can’t make up for the decades of abuse heaped upon this low-income community. However, the hundreds of protesters who turned out to last night’s public hearing, held in Detroit’s River Rouge neighborhood to review Marathon’s proposal, have big plans. Although 22 tons more of sulfur dioxide may seem negligible for a plant that releases over 200 tons each year, the issue has provided a much-needed media hook for the Detroit community. The well-organized opposition is drawing attention to larger issues, and, following massive media focus on Flint’s water crisis, the hearing made news in dozens of print and online publications.

Andrew Sarpolis admits that it’s a bit of a stretch for Michigan’s Beyond Coal Campaign to be putting so much effort into thwarting an oil refinery, but finds relevance in the emphasis on cleaner air, a major focus of Beyond Coal.

The area is already in nonattainment for sulfur dioxide, meaning its levels are in violation of EPA standards. On the precipice of the MDEQ’s decision, resistance couldn’t be more urgent. As Anderson explains, “The community is overburdened with toxic emissions. We don’t usually have the luxury of being able to say, ‘This pollutant is the most important.’”

According to Anderson, “Marathon says that down the line, this will mean a reduction in automobile emissions – but it doesn’t bode well for the community. We are the ones hit first with pollution, before reductions can even take place.”

Anderson draws a parallel between this battle with Marathon and the unfolding two-year water crisis in Flint. In an attempt to cut corners on the state’s budget, Flint’s water supply was redirected from Lake Huron to the notoriously unclean Flint River. Soon, residents noticed their tap water was running red with iron, and their toddlers were getting sick and losing hair. This turned out to be lead poisoning. The toll now stands at 10 dead and 10,000 sickened. Michigan Governor Rick Snyder was pressured into releasing 273 pages of emails pertinent to the unfolding scandal; the documents, a concerning number of which are censored, reveal that the governor’s office tried to evade responsibility by allocating blame to Genesee County and the City of Flint, which lacked the water quality data and tax revenue to take up the issue.

Like Detroit, Flint is an industrial, primarily black city. Ironically, the state legislature found the budget cuts necessary because Michigan’s economy was suffering from auto industry failings. The health of an entire community was gambled away in an attempt to clean up the state’s finances, put at risk by the same industries doing the polluting.

“We were Flint before Flint was Flint,” Theresa Landrum avows. This seems the perfect retort to an MSNBC article released yesterday, titled, “Will Detroit be the next Flint?” “Like them, we find our water poisoned, but it’s also our air and land.” Heavy metals and noxious gases are pumped daily into the surrounding environment by a slew of different industries, and as Landrum says, “What goes up must come down.”

“All environmental justice communities are sacrifice zones,” Anderson asserts. “To the government, Flint was expendable. The residents didn’t matter. The governor didn’t think he’d get caught, and it’s the same thing with the MDEQ. Flint was just the one that got exposed – it’s easier to see contamination in water than it is in air.” But Landrum describes a visibly decimated landscape in Detroit: “We are under a blanket of pollution. The toxic atmosphere sits, is held there. It is not dissipating.”

If there’s any good that might come of Flint’s scandal, it’s the flagrantly irresponsible MDEQ being held on a tighter leash by national attention. State legislators, Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, and the director of Detroit’s City Health Department are standing with the 48217, sending a strong message that the well-being of residents is non-negotiable.

The Sierra Club is determined to push back against the MDEQ, which reported in its statement on the Marathon proceedings that the proposed increase in emissions “would continue to meet health protective standards.” Whatever these “health protective standards” are, they are insufficient. The affected community knows it. The 48217 zip code is an environmental battleground, and residents are taking up arms in the form of social activism.

“Governor Snyder is at the head of this,” promises Anderson. “He’s been allowed to literally kill people – and he thinks, ‘They’re not valuable. Poor black people? Poor brown people? Even poor white people. Who cares?’”

Clearly, Anderson and her fellow activists in the Michigan Chapter of the Sierra Club care immensely. It’s time that Detroit sees the justice it deserves.