You Can Get a Crazy Amount of BPA from Cash Register Receipts

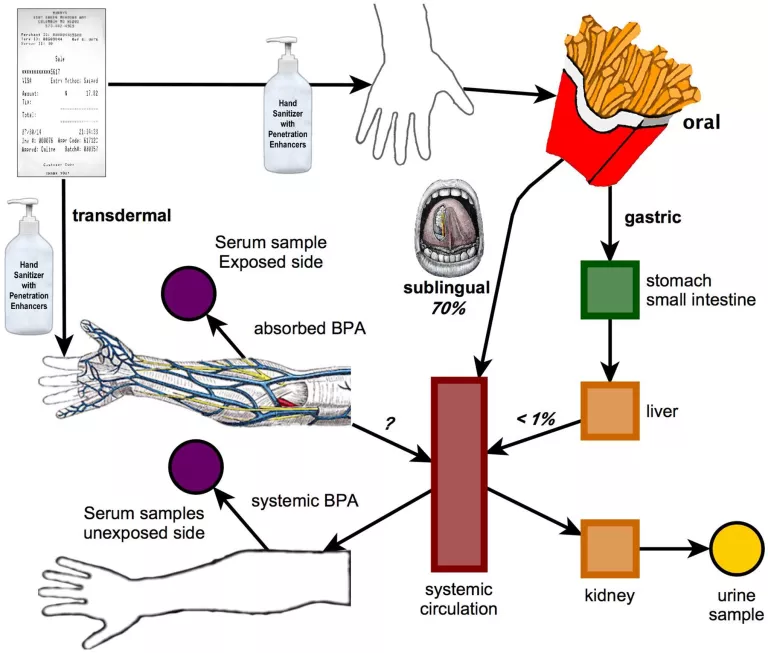

Schematic diagram of the transmission of BPA from thermal receipts to your skin and the food you eat.

Ever since early exposes showed the endocrine-system-disrupting effects of the industrial chemical BPA, manufacturers have discontinued its use in water bottles, baby bottle, and binkies. (That's why everyone drinks their water out of metal containers these days.) In estimating human exposure to the chemical these days, federal regulators assume that the main source of exposure to BPA is from food and beverage packaging. However, a new study by Frederick vom Staal and others in the journal PLOS One shows that another significant point of entry could be handling of thermal receipts--those ubiquitous slips of paper that come at the end of nearly every financial transaction--especially if you have used hand sanitizer or various other skin creams. Doing so, the study found, can increase uptake of BPA 100-fold. Worse, if you handle a BPA-coated receipt and then eat food with your hands, you ingest the BPA as well.

We found that when men and women held thermal receipt paper immediately after using a hand sanitizer with penetration enhancing chemicals, significant free BPA was transferred to their hands and then to French fries that were eaten, and the combination of dermal and oral BPA absorption led to a rapid and dramatic average maximum increase (Cmax) in unconjugated (bioactive) BPA of ,7 ng/mL in serum and ,20 mg total BPA/g creatinine in urine within 90 min.

The implications for the fast-food industry are pretty clear.

To assess the relevance of this research to real-world behavior, we conducted a preliminary observational study in fast-food restaurants, food courts and shopping malls in Columbia Missouri. Receipt contact time varied widely, but was sometimes substantial. In one restaurant, we found that receipt contact time ranged up to 65 sec for people purchasing food that was eaten in the restaurant; the 75th percentile for time holding the receipt was .12 sec, and the 90th percentile .32 sec. In a fast-food restaurant that is part of an international chain, take-out food was placed into a bag and the top of the bag was folded, then the thermal receipt was stapled to the top of the bag; the result was that the print surface of the receipt (coated with BPA) was grabbed when the bag was picked up. The contact time between the hand and thermal receipt was thus considerably longer than would be the case for food eaten in the restaurant. In a food court we observed that some fast-food restaurants had hand sanitizer dispensers available for use by customers next to the cash register, and customers were observed using the hand sanitizer before handling the thermal receipt. The estimate is that 50 million people eat in a fast-food establishment every day in the USA. Finally, our experiments here are also relevant to occupational exposures, because we observed in a national chain big-box store that all cash registers had a hand sanitizer dispenser next to them for use by the cashiers.

And if you're looking for investment opportunities, you might want to check out alternatives to those thermal-receipt machines. As the authors conclude:

Because no safe alternatives to the use of BPA or its primary replacement chemical BPS in thermal paper have been identified, our findings provide support for the EPA’s recommendation that thermal paper should be replaced with other safer technologies.

Finally, the study's results suggest a prudent course of action for shoppers:

"Receipt?"

"No thanks."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club