Is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault Truly Impregnable?

How “Noah’s Ark of Plant Diversity” will weather a changing climate

Photos courtesy of Landbruks- og Matdepartementet

A sharp concrete slab emerging from a permafrost mountain in an archipelago in the Arctic Circle bears an art installation that casts light in all directions. It’s the only clue to the importance of what lies inside.

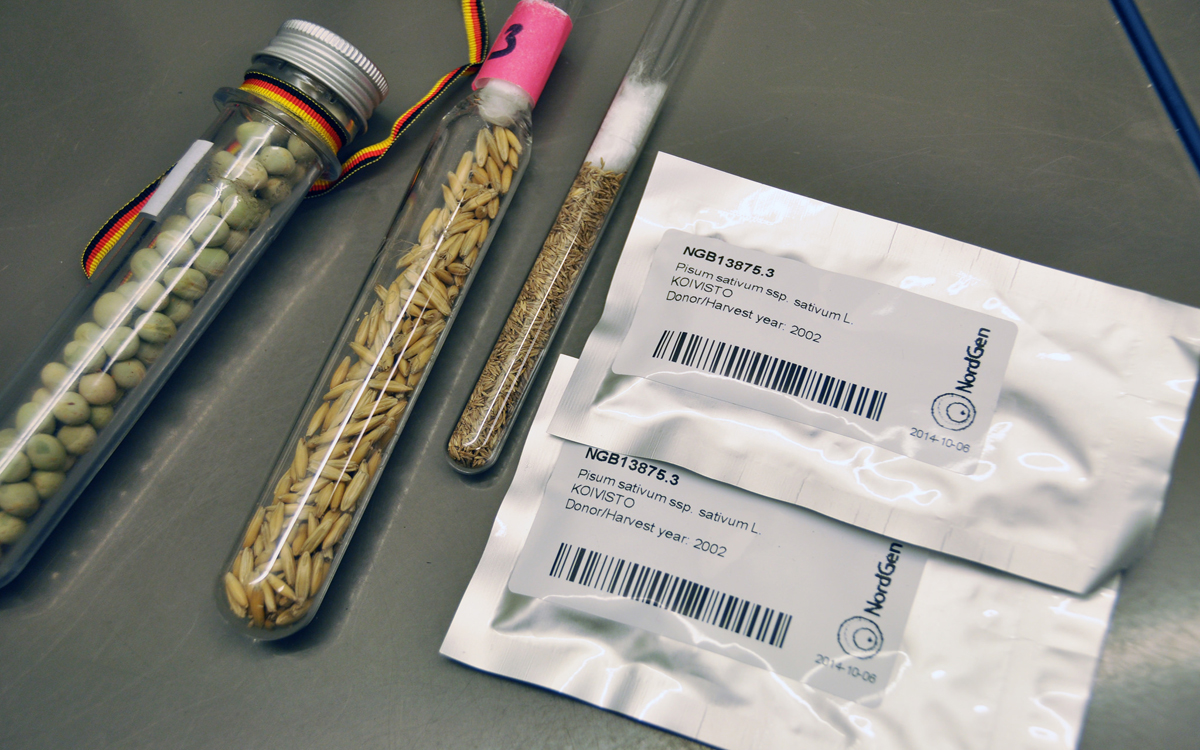

This is the sole visible-from-the-outside part of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Deep within the mountain are three caverns designed to accommodate samples of up to 4.5 million types of seeds from all over the world, cataloguing 13,000 years of agricultural history. Those seed types that are important for food and agriculture are given priority. All seeds are duplicates of samples already held in more than 1,400 gene banks worldwide.

All that came into question in May, however, when major news outlets including the Guardian reported that there had been a water intrusion, and that warmer, wetter Arctic weather was the cause. Enter climate change.

The event had actually taken place on October 15, 2016, and was described as a “water intrusion due to extreme weather with a lot of rain and high temperatures,” according to Hege Njaa Aschim, communications director for Norwegian Government-led organization Statsbygg. “The seeds and the vault were never at risk, but the water came about 66 feet into the entrance of the tunnel leading to the vault. It froze, and we had to take it out by hand, which took a few days.”

At the time, Norwegian and Swedish media covered the event. In May, The Guardian picked up the story from Dagbladet, a Norwegian newspaper, citing the incident as “flooding.” The piece went global, causing many to think there had been an additional water intrusion. “The story has been covered in more than 1,100 international media, and we have had the opportunity to tell our story on 40 radio and TV channels all over the world,” says Aschim.

The world’s largest collection of crops’ genetic diversity is not a Doomsday Vault for a remote future following some kind of apocalypse, but is rather intended to function as a back-up stock of seeds to guard against the risk that existing gene banks could be destroyed as a result of war, pollution, or, perhaps most pressingly, climate change. “Gene banks face continuous problems, and many gene banks have lost their seeds, unfortunately without having deposited duplicates in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault,”says Åsmund Asdal, the Vault’s coordinator for the Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen). “When duplicated in the vault, seeds will not go extinct. To date, only one gene bank has retrieved their seeds from the vault: ICARDA, the international center that had its gene bank outside Aleppo in Syria.”

Svalbard, situated halfway between Norway and the North Pole, was long believed an ideal vault location, and not merely thanks to its remoteness and distance from conflict. Even during midsummer, when temperatures hover around 40 degrees Fahrenheit, mountaintops are still draped with snow, and vast glaciers sweep across the islands. Permafrost keeps residents from farming, and despite a few small projects, most food is shipped from mainland Norway. In Longyearbyen, the archipelago’s capital, wooden pilings from long-gone buildings stick out of the earth like rotten teeth—as the permafrost shifts, it pushes matter out.

At 78˚ North, the vault’s surrounding Arctic permafrost means that the temperature should never exceed 25˚ Fahrenheit, even in the event of a power cut and subsequent cooling system failure. Cooling systems in seed storage bring the temperature down to -4˚ Fahrenheit—the same temperature seed banks keep for their seed collections.

“When the seed vault was built in 2007 and opened in 2008, the purpose was to store seeds in permafrost with possibilities for additional artificial cooling. The intention was not to make something ‘climate change-proof,’” says Asdal. “As in other areas, the knowledge about climate change has developed and evolved gradually, and is on a totally different level today, compared to when the plans were discussed and made.”

“When the seed vault was built in 2007 and opened in 2008, the purpose was to store seeds in permafrost with possibilities for additional artificial cooling. The intention was not to make something ‘climate change-proof.’”

Before October’s water intrusion, Statsbygg had already planned to take measures to waterproof the tunnel, so as to provide additional security as Svalbard’s climate becomes wetter and warmer—the Arctic Circle is not exempt from the fact that 2016 was the warmest on record globally. It’s part of why about $1.7 million has been set aside for the seed vault improvements. These include the removal of heat sources in the access tunnel, construction of drainage ditches on the mountainside (to prevent meltwater accumulating near the access tunnel), the construction of waterproof walls inside the tunnel, and consideration of alternatives for a new access tunnel. The group conducting the investigations and design work for the improvements is scheduled to submit a proposal outlining further suggestions in spring 2018. Statsbygg is also carrying out a research and development project to monitor Svalbard’s permafrost, and The University Centre in Svalbard, too, is conducting ongoing permafrost research.

“The water intrusion did not change our plans,” says Aschim. “But it did cause us to work more rapidly.”

Fewer than three miles from the seed vault, recent avalanches in Longyearbyen also point to a warming climate. There, increasingly widespread concern about hillside instability, due to thawing permafrost, has Norwegian officials scouting future spots for new buildings—places located a safe distance from the permafrost mountains, but still within the settlement. However, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault won’t be being relocated anytime soon, as officials feel planned improvements will sufficiently address climate change-related concerns.

Fewer than three miles from the seed vault, recent avalanches in Longyearbyen also point to a warming climate. There, increasingly widespread concern about hillside instability, due to thawing permafrost, has Norwegian officials scouting future spots for new buildings—places located a safe distance from the permafrost mountains, but still within the settlement. However, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault won’t be being relocated anytime soon, as officials feel planned improvements will sufficiently address climate change-related concerns.

For information about those seed samples conserved, consult the Svalbard Global Seed Vault’s Seed Portal.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club