Image via Canva Pro: Pgiam

By Neil Carman, Clean Air Director, Sierra Club Lone Star Chapter

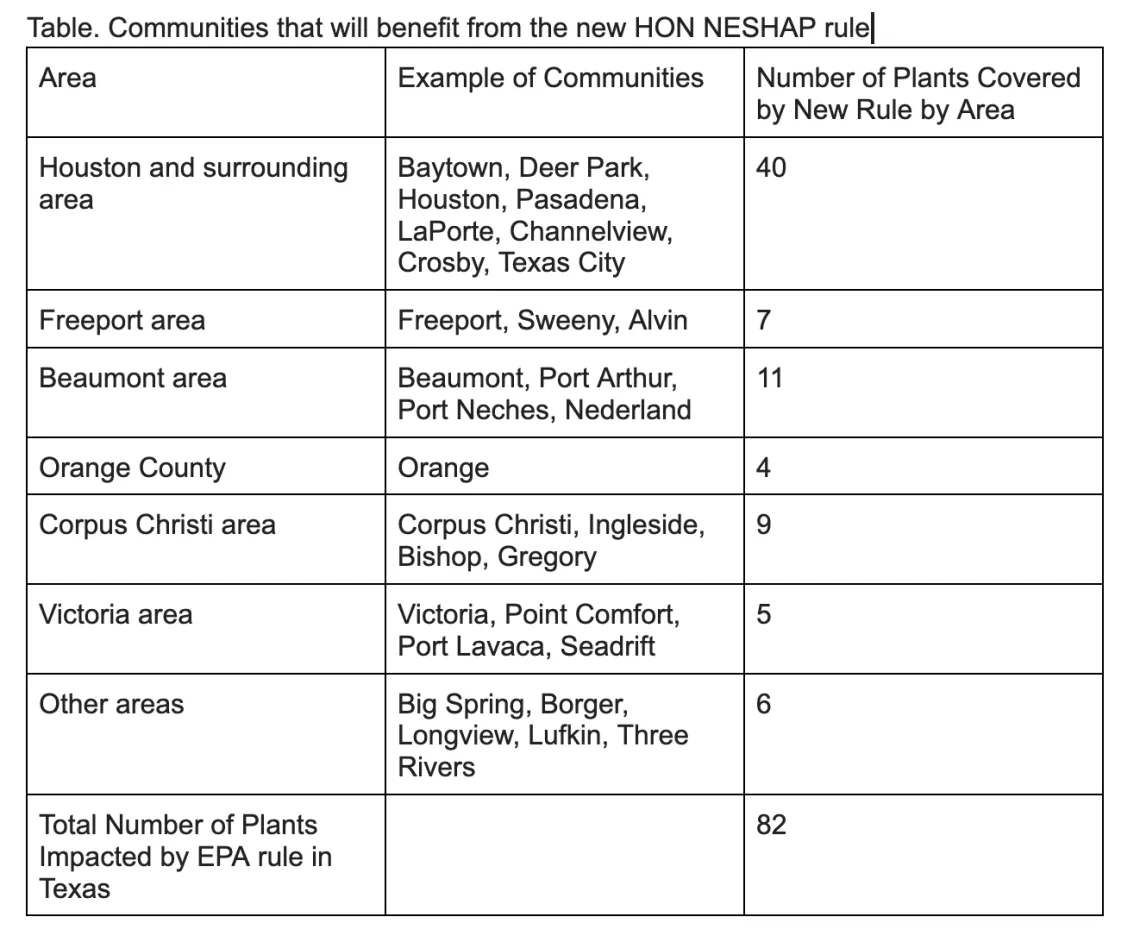

Well, it took a couple decades of organizing and legal efforts, but on April 9th, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finally adopted new Clean Air Act standards for chemical plants to lower toxic air pollution in fenceline communities by 6,200 tons. No state has more major chemical plants impacted by the rule than Texas. Under the final rule, released a year after an initial proposal, EPA is updating critical Clean Air Act standards that will reduce toxic emissions from more than 200 of the nation’s most hazardous chemical plants. All told, 82 large Texas chemical and petrochemical plants will have to install fenceline air monitoring systems (similar to fenceline benzene monitoring at oil refineries). About two-thirds of the plants are found either in Texas or Louisiana. The rule is intended to prevent cancer in surrounding low-income and minority communities, which have been sacrifice zones with high cancer rates for decades.

Plants emitting ethylene oxide, chloroprene, vinyl chloride, 1,3-butadiene, benzene, and other carcinogenic chemicals will have to make reductions in toxic emissions from their chemical process units, safety vents, equipment fugitives, emergency flares, storage tanks, and other sources.

This progress resulted after decades of organizing and specifically from a legal action taken several years ago where groups, including the Sierra Club, sued EPA over its failure to review the need of new air toxics rules in the last 20 years. It is a significant step forward to protect the right to clean air in Environmental Justice (EJ) communities.

Ethylene oxide has emerged from cancer studies in the last ten years as posing grave concerns in fenceline communities, because the EPA’s toxicologists discovered that it’s a more potent human cancer-causing agent than other carcinogens listed above. Indeed, ethylene oxide is similar in cancer toxicity to the super carcinogenic dioxins and dibenzofurans that the contaminated herbicide Agent Orange used in the Vietnam War.

However, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) could throw a horrible monkey wrench into the EPA’s ethylene oxide standard applied in Texas if it gets its way. TCEQ’s toxicologists have been working on an alternative, weaker standard the agency seeks to apply at 60 chemical and petrochemical plants in 26 Texas communities, which would sabotage the EPA standard. TCEQ is working through an expert panel at the National Academy of Sciences to weaken the EPA’s Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS) risk factor for ethylene oxide and replace it with a far weaker TCEQ toxicology standard many times less protective than EPA’s IRIS risk standard. Recently, I testified to the expert committee at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine about its review of TCEQ's Ethylene Oxide Development Support Document (2020).

In addition, in January 2024 at a TCEQ public meeting in Laredo on Midwest Sterilization’s commercial sterilizer, a TCEQ toxicologist stated that the agency has the authority to use TCEQ’s weaker ethylene oxide standard rather than EPA’s at commercial sterilizer factories in Texas. A serious concern is that TCEQ may also apply its own standard to the 60 chemical and petrochemical plants, allowing more ethylene oxide to be released into those EJ and fenceline communities.

TCEQ failed to release the ethylene oxide information used to propose its draft Development Support Document (DSD) in June 2019. By contrast, the EPA conducted a first-of-its-kind, comprehensive community risk assessment, which can be found here. For communities within about 6 miles of a chemical plant, the new EPA rule would reduce cancer risk by “96 percent in those communities overall, with the biggest reductions occurring in the areas where risks are highest.”

The cancer risk factor is highly controversial—TCEQ’s standard is orders of magnitude less protective of public health than the factor that EPA scientists published after robust, systematic, scientific process and peer review. TCEQ’s factor does not account for breast cancer, ignores in-utero exposure, and makes the unsupported assumption that Texas communities should be allowed to breathe a significant amount of ethylene oxide without any protection, even though there is no safe level of exposure to such a potent carcinogen. (Note that TCEQ revised the draft 2019 DSD and released a new draft DSD on January 31, 2020 with a slightly improved ethylene oxide standard, but it was still much weaker than the EPA’s IRIS risk factor.)

Where does all this sudden action come from?

Under the federal Clean Air Act, EPA action on hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) was slow, and initially only a few carcinogens – such as benzene and vinyl chloride – were covered in the early 1980s under the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP), which are stationary source standards for hazardous air pollutants. In 1990, due to EPA’s failures to adopt standards for more HAPs, the Congress changed that NESHAPS gap by amending the CAA and establishing Title III Air Toxics with 189 chemicals. However, despite the requirement that EPA develop standards for these additional toxic pollutants, EPA's slowness, lack of funding, and legal actions by industry to slow down and stop this type of progress has meant the promise of protecting communities from these toxics has not been realized. Frontline community groups, along with national groups like the Sierra Club, Earthjustice and other organizations have been suing the EPA since the early 1990s to fully implement the 1990 CAA Amendments.

The rules adopted last month are part of a consent decree reached by Sierra Club and other partners to cover these particular HON (Hazardous Organic NESHAPS) rules. The HON rule covers more than 100 air toxic chemicals for 227 chemical and petrochemical plants in the U.S. Of those 227 plants, 82 are located in 30+ Texas communities, most of them along the Gulf Coast.

Many communities in Texas will benefit from new air toxics reductions and, of course, these air toxics are also ozone-precursors, meaning they eventually contribute to ground-level ozone, commonly known as “smog.” Many of these chemical and petrochemical plants are sited in the area of Houston that already exceeds safe levels of ozone.

These chemical and petrochemical plants include hundreds of thousands of pieces of equipment in HON liquid service such as benzene. Though there are some Leak Detection and Repair (LDAR) programs in place, stronger LDAR efforts are needed to cover the vast numbers of liquid pumps, valves, flanges, compressors, and other pieces of equipment.

Emergency flare systems are directly affected by the new EPA rules, with plants needing to reduce HON chemical flaring events due to process unit problems as well as upsets, and working to ensure more efficient incineration of HON air toxics to water and carbon dioxide. Otherwise, unburned air toxics are released and de novo air toxics are formed such as PAHs, (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) containing PM2.5 soot particles which are highly carcinogenic.

To ensure the results of fenceline monitoring are available to communities, EPA will make the monitoring data publicly available on its WebFIRE webpage. The fenceline monitoring provisions in the final rule are modeled on similar Clean Air Act requirements for petroleum refineries first established in 2015, which have been historically successful in identifying and reducing benzene emissions.

So Everything Is Fixed Right?

No, not yet. In addition to TCEQ asking for a review of the ethylene oxide standard through the National Academy of Science, a number of other entities including TCEQ (through Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office), various other conservative states, as well as industrial groups like the American Chemistry Council and Huntsman Petrochemical have now gone to the D.C. Court of Appeals, essentially saying the U.S. EPA has gone too far in this new rule. Does it surprise anyone that our environmental regulator and state officials are legally on the same side as Huntsman Petrochemical and other large corporations?

And what is the Sierra Club doing? We are joining with other environmental and community organizations in filing a motion to intervene in support of the EPA final rule and standards. Joining the Sierra Club in our motion are Rise St. James, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, Louisiana Environmental Action Network, Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, Air Alliance Houston, Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League, Inc., Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, Environmental Integrity Project, and Union of Concerned Scientists.

We are also gearing up for an important legislative interim hearing on Wednesday, June 13th when the Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Economic Development will be taking up a charge looking at “Overcoming Federal Incompetence” of the Biden administration in moving forward with rules on air quality. We will be there to defend this rule and many other federal rules and proposals, and any member of the public can show up and testify. Here are the deets – that public meeting is open to anyone. And of course, legal work, motions to intervene, and organizing are not free, so please consider donating to the Lone Star Chapter or other organizations involved in this important work!