Image by akaratwimages

By Dr. Neil Carman and Dr. Cyrus Reed

It’s easy to forget about ground-level ozone, often referred to as smog. In the upper atmosphere, ozone helps us by protecting us from the sun’s radiation, but at ground-level it is a dangerous and devastating pollutant, searing our lungs. Texas’s major metropolitan areas, including Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston-Galveston-Brazoria, have a more than 45-year history of taking too long to meet the four federal ozone standards established by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Some good news is that since 2010, the Houston and DFW areas did meet the old one-hour standard set in 1979 and the first eight-hour standard set in 1997.) But while there has been clear improvement in recent years in the levels of pollution – indeed, cars and trucks are getting cleaner, large industrial sources are required to meet stricter permit levels, older power plants are shutting down and being replaced, and more electric vehicles are on the roads – Texas still has a long road ahead of it to come into compliance with current smog safeguards. And recent evidence isn’t looking good.

First, the extreme Texas summer heat not only ramped up pollution from power plants that directly contribute to the gasses that create ozone, but the intense heat and sunlight likely led to higher ozone levels. Put simply, hotter sunnier days lead to higher levels of ozone since sunlight is a necessary ingredient in creating ozone: literally three oxygen atoms briefly bonded together for a few seconds that combine and separate over and over again due to high smog chemical concentrations. That ozone forms when volatile organic compounds (think highly reactive toxic gasses like acetylene, ethylene, propylene, butene, 1,3-butadiene, butylene, and less reactive benzene and formaldehyde) combine with nitrogen oxides (think combustion of fossil fuels) in the presence of strong sunlight, calm winds, and cloudless skies.

Second, in addition to Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth, San Antonio and El Paso are also routinely violating the two most recent ozone standards set in 2008 and 2015, with one new potential entry – Austin – also pushing (slightly) above the standard.

Third, the U.S. EPA stepped in and slapped the state of Texas with a real threat – either improve your “State Implementation Plan” to include meaningful contingency measures to reduce ozone pollution, or face the threat of potentially losing federal highway dollars and potentially facing a federally imposed Implementation Plan. Meanwhile, we are still awaiting a final decision on a newly reinvigorated rule – the Good Neighbor Rule – which could require significant cuts in summer emissions from coal and other large industrial plants that are contributing to higher ozone levels both in Texas and in other states.

So How Bad Was the Summer of 2023 on Ozone Levels?

Well it wasn’t the worst in history but it was pretty bad. The highest levels found during the ozone season (generally late May to early October) were not surprisingly found in Houston, with the highest level being recorded at 114 parts per billion (ppb) over an 8-hour period in West Houston on May 18th. The current health-based maximum standard for ozone is 70 ppb. But that reading – some 163% over the health-based standard – was just one of hundreds of readings in Texas major metropolitan areas that violated the health-based standards.

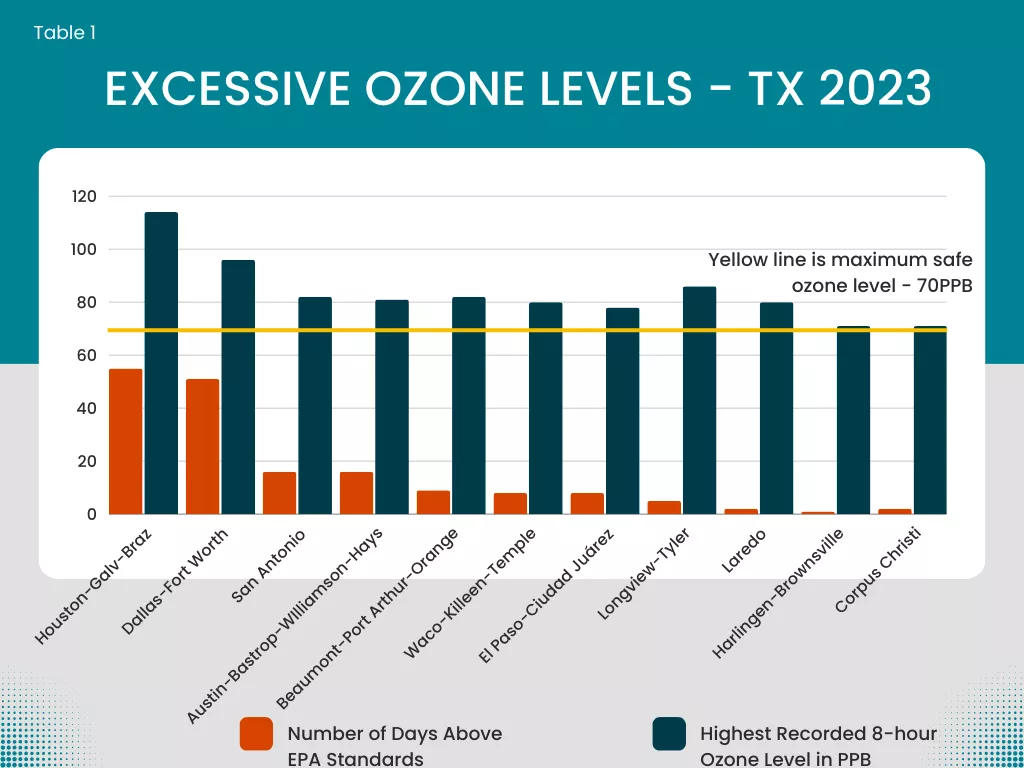

Table 1 shows the number of days that different regions experienced where ozone levels were above the current health-based standard of 70 parts per billion. It’s a lot, and found all over the state. Just because a region has up to three days above the standard does not mean it is technically out of compliance. EPA allows up to three high ozone days a year at a monitor, and this approach has been applied by EPA since the 1970s.

Table 1. Number of days that different air quality monitoring areas had high ozone levels that exceeded health-based standards

Based on these readings, for example, Houston-Galveston-Brazoria suffered from 55 days where at least one monitor registered more than 70 ppb, while Dallas-Fort Worth had 51 days where it was considered not safe to breathe for certain populations. Both the San Antonio metro and Austin areas registered 16 days with elevated levels of ozone, while other areas like El Paso, Waco and Longview-Tyler also had multiple unsafe days. Even South Texas had a few days where ozone levels were elevated.

Short-term levels above the standard do not equate to non-compliance, however. The compliance equation looks at:

- national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS) based on measurements of ozone over an 8-hour period,

- the fourth-highest reading averaged over three years at a certified air quality monitor, and

- whether the average over three years of the “fourth-highest” reading at a particular air monitoring station is above 70 ppb.

Table 2. Shows the fourth-highest ozone levels in 2023.

(A map with locations of all the air quality monitors in Texas can be found here.)

As reflected above, seven of the 10 metropolitan areas measured by TCEQ and private monitoring networks found at least one day that violated the fourth-highest day standard. (Which again does not equal non-compliance since non-compliance is based on a three-year average). Five of those seven – Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, San Antonio, El Paso, and yes now even Austin, are now in violation of national air quality safeguards.

Wait, did you say Austin now violates the standard?

Okay, it’s too soon to declare the Austin metro area to be in non-compliance with the ozone standard. That takes a finding by the EPA that quality-assured data shows a level above 70 ppb over three years of data, and would also require extensive input from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, local officials, and the public. But at the very least, the U.S. EPA will be looking at the evidence.

The worst monitor in Travis County is at Murchison Middle School on Northwest Hills Drive in far Northwest Austin, which averaged 71 ppb for three years (although the TCEQ's ozone monitor data will not be validated until early 2024 by the TCEQ). This monitor site is close to the MoPac freeway and not that far from IH-35 and SH183. Winds from the southeast transport the ozone and precursors to the Murchison monitor. Until this data is confirmed it is difficult to know whether this air monitor will be found to be out of compliance.

In addition to the Murchison air monitor, the Austin-metro-area monitor with the worst levels of ozone pollution is in Dripping Springs (Hays County). This monitor is operated by the Capital Area Council of Governments (CAPCOG) and it is considered to be a "non-regulatory" monitor, not to be used for nonattainment determination. That monitor shows even higher levels of ozone.

CAPCOG has asked the EPA 6 Dallas Ozone SIP staff about allowing CAPCOG's 10 monitors to be used for nonattainment determinations, but EPA continues to declare it a "non-regulatory" monitor as the TCEQ is avoiding designating any parts of the Austin 5-county region in nonattainment. The CAPCOG monitor C614 in Dripping Springs has had 4th highest values in 2021, 2022 and 2023 of 69, 81 and 78 respectively. Thus, the three-year average equals 76 ppb – well above the EPA's 2015 NAAQS of 70 ppb.

Texas currently has four confirmed ozone nonattainment areas (NA): Houston-Galveston-Brazoria's 8-county NA, Dallas-Fort Worth's 10-county NA, San Antonio’s 1-county NA, and El Paso’s 1-county NA. That's 20 counties among 254 counties in Texas.

Yet these four ozone nonattainment areas – areas where ozone levels are consistently unsafe to breathe – are very large population centers where more than half of Texans live.

Houston, which has the highest levels of ozone, is the nation's largest industrial hub for the chemical, petrochemical, and oil refining sectors, plus enormous supporting infrastructure. In fact, the City of Houston alone has over 10,000 small businesses with minor levels of air pollution that are visible everywhere you travel in the city and Harris County areas.

Will other cities (beyond the four NAs above) change ozone designation status from attainment to nonattainment?

Not likely at this time, even though there were monitors with ozone exceedances in Beaumont/Port Arthur/Orange, Waco/Temple/Killeen, Longview/Tyler/Marshall, Corpus Christi, Victoria, and Harlingen and Laredo in the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

Except for Austin’s high ozone levels, all other major cities with ozone monitors do not show a nonattainment potential using the 2021-23 ozone data based on either the 2015 EPA standard of 70 ppb or the 2008 EPA standard of 75 ppb.

Okay, if EPA is going to take its time to weigh in on non-attainment issues in Austin, is it doing anything to help lower ozone levels in Texas?

Yes. Recently, the EPA took a few important actions.

First, the Environmental Protection Agency, in a ruling issued in October, rejected the plans submitted by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to comply with the ozone standards for both the Dallas and Houston areas. At issue is the Houston and Dallas regions' longstanding noncompliance with federal ozone standards under the Clean Air Act. Basically, in nicer words, the EPA told Texas officials they need to do more to lower ozone levels in the two large metropolitan areas. If the TCEQ does not improve the plan and show real progress, EPA could intervene and issue sanctions. If Texas does not submit an acceptable ozone-reducing plan for those metropolitan areas by November 2025, the EPA said a federal plan will be implemented, and those areas could lose out on federal highway funding. The TCEQ has yet to respond. Sierra Club for years has advocated for a number of required improvements in permits and standards from thousands of small and large industrial sources of air pollution, from refineries, to Portland cement plants, to oil and gas drilling activities, to coal plants. We stand ready to again suggest those improvements to help assure safer air quality for millions of Texans.

Second, this year, in March of 2023, the US EPA issued a new “Good Neighbor Rule” – officially called the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, that would require large coal plants and certain other facilities to significantly decrease emissions of nitrogen oxides in the coming years in order to reduce the transport of ozone and its precursor chemicals into our metropolitan areas. Here’s where it gets pretty complex. The EPA plan requires action in 23 states, including Texas, as our large, polluting coal plants contribute to pollution both within Texas, but also transport pollution clouds into other neighboring states. However, the plan endorsed by the EPA is subject to multiple lawsuits, meaning while part of the plan is likely to go forward, other parts are still being hashed out in court, including the specific budget and reductions that coal plants would be required to meet. The Sierra Club is a litigant in these suits playing out in federal court, but we believe in the end, coal plants and other large industrial sources will be required to cut their NOx emissions even further than the NOx reductions in previous years, particularly during the hot summer months. Not surprisingly, the State of Texas, through embattled Attorney General Ken Paxton, is helping to lead the charge against cutting pollution from dirty coal plants. At least we know whose side he stands on!

Information about the Good Neighbor Rule can be found here.

Okay, so what can we do?

Sierra Club is looking into how we can pressure both TCEQ and the EPA to take further measures to clean up our air, including specific actions on oil and gas, coal plants, transportation, and use of federal funds. We are also exploring legal action we might take. But there is no doubt that public pressure can help.

Ozone is a killer and only through public pressure, strong federal rules, and legal action will we get our state regulator and local officials to do what is needed to keep our communities safe! Stay tuned for future actions you can take.