By Myron Hess, Water Programs Manager/Counsel at National Wildlife Federation

Note: This article was originally published on the Texas Living Waters Project (TLWP) blog.

TLWP is a collaboration of conservation groups - made up of the Sierra Club, National Wildlife Foundation and Galveston Bay Foundation - working to transform the way we manage water so there will be enough for our wildlife, our economy and our kids.

Sometimes the work of the Texas Living Waters Project (TLWP) gets a little confrontational. While admittedly not as scintillating as scripted court hearings on cable TV featuring professional actors and colorful plot lines, the TLWP uses the state’s contested case hearing process, when necessary, to fight for Texas rivers and bays.

When significant new permits or permit amendments are proposed that we believe may cause substantial harm to our waterways, wildlife or economy, we try to negotiate stronger protective conditions. Those conditions are needed to prevent permitted water withdrawals from causing water flows in rivers and creeks to fall so low that fish and wildlife are seriously harmed, including by depriving coastal bays of needed fresh water. When protective conditions are included, they usually limit how much water can be taken out, stored or diverted from the river by requiring that some amount of water flow must be allowed to pass downstream.

Often we are able to work with permit applicants to agree on stronger water and wildlife protections than the ones proposed by Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) staff, who review all water permit applications and develop draft permits. But when an applicant won’t agree to reasonable protections or a project is so damaging that it should not go forward at all, Annie Kellough Schmitt and I put on our lawyer suits and use the court-like hearing process to fight to protect critters like river otters, Guadalupe bass, blue suckers (a state-listed threatened fish species), and Texas pimplebacks (a state-listed threatened mussel species).

River otters benefit from the work Texas Living Waters Project does to protect healthy rivers and wildlife. / Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Most recently, Annie and I used the hearings process to challenge an amendment application by the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA).

Protecting The Colorado River And Its Water-loving Wildlife

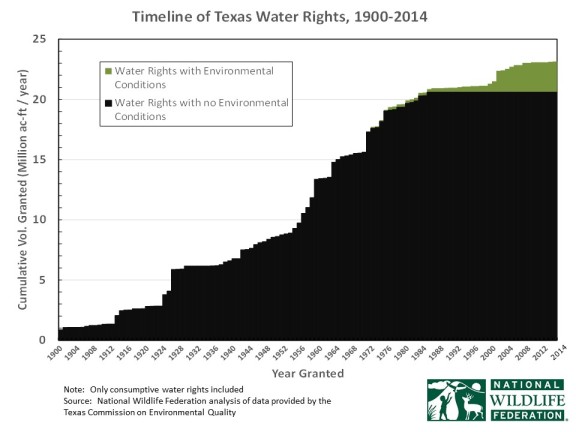

The water flowing in streams and rivers belongs to all Texans, but the TCEQ issues perpetual permits to allow people to take water out of a river or intercept that river’s natural water flow by constructing projects like dams and reservoirs. Even though the state has been issuing those types of authorizations since the late 1800s, only in the last 30 years or so have the authorizations included any conditions to protect water quality and the fish and other critters that depend on those water flows to survive. This means that the vast majority of Texas water rights in existence today do not include any requirement to leave enough flow for healthy rivers, bays and wildlife.

The black section of the chart represents all of the water rights in Texas that do not include conditions to protect rivers, bays and wildlife. The green section shows how few water rights include conditions that protect the environment.

LCRA has an existing permit, issued in 1900, allowing it to divert 133,000 acre-feet of water from the Colorado River at a point far downstream of Austin. For context, an acre-foot is the amount of water that would cover an acre of land (about the size of a football field from goal line to goal line) a foot deep, which equals about 326,000 gallons. This permit was issued without any limits to protect the Colorado River or the many fish and other critters that call it home.

Now, LCRA has applied for an amendment to their permit that would allow the full amount of water to be taken out as far upstream as Lake Travis. Taking it out there would deprive about 175 miles of the Colorado River of that amount of water flow. Without adequate flow protections, this could threaten 175 miles of wildlife habitat – for critters like river otters, Guadalupe bass, and herons – and the Texans who enjoy it, by depriving it of the water flow needed to maintain healthy conditions.

In place of the inadequately protective draft amendment that TCEQ staff developed in response to LCRA’s application, the TLWP team proposed a very reasonable approach that would still allow LCRA to make the upstream diversions while also protecting the river and wildlife. This approach would include permanent protections to prevent the diversions from dropping river flows low enough to cause serious harm. Based on our history of a good working relationship with LCRA, we were optimistic about the prospects for a negotiated resolution. Unfortunately, things seem to have changed at LCRA.

Not only was there no agreement, but LCRA never even provided a response to our detailed settlement proposal. That led to the hearing and a heated exchange about whether LCRA’s request to divert that full 133,000 acre-feet at Lake Travis falls under its current permit, or whether it represents a new water use appropriation. If it is a new appropriation, certain minimum levels of permanent flow protection are automatically mandated by TCEQ rules. If not, the specific level of protection is determined on a case-by-case basis. Regardless of that decision, we presented evidence that better protection is required than the draft permit provides.

Keeping Our Lawyer Suits At The Ready

Over the coming months, the various parties to the hearing will file written legal arguments about the appropriate interpretation of the evidence presented and about the flow protections that should be ensured. Then, the Administrative Law Judge who heard the evidence will develop a Proposal for Decision (PFD). Unless LCRA decides to negotiate, sometime next year the three commissioners at TCEQ will consider the PFD and the arguments of the parties and make a decision.

Contested case hearings are labor intensive but vitally important. They give us the opportunity to make sure that new perpetual permits and amendments governing the water owned by all Texans include strong conditions to help maintain healthy rivers and bays. The hearings also help ensure that river-front landowners, other water right holders, recreational and commercial fishers, and organizations like ours can protect their interests, including the interest in healthy fish and wildlife. Our organizations can only participate in a hearing when we are able to identify individual members who would be directly affected by the change being requested.

Since the late 1800s, the state has issued perpetual authorizations to divert and consume more than 23 million acre-feet of water from Texas streams and rivers. In the approximately 17 years of TLWP’s existence, through negotiation and contested case hearings, our team has improved the flow protections governing about 2.5 million acre-feet of water – that’s 2.5 million football fields, each covered with a foot of water – in Texas streams and rivers. Even though that is a good start, much more remains to be done on behalf of pimplebacks, bass, suckers, otters, and our precious rivers and bays, so we are keeping our lawyer suits at the ready.

About The Author: Myron Hess

When not working on legal and policy issues related to water quantity and quality, Myron likes to head outdoors in search of a bird, whale, crayfish, praying mantis, or just a cool plant. He also enjoys exploring Texas streams and springs, listening to singer-songwriters, traveling, and learning about new developments in science.