Woman as Medical Waste

A cancer survivor reflects on the downstream costs of her treatment

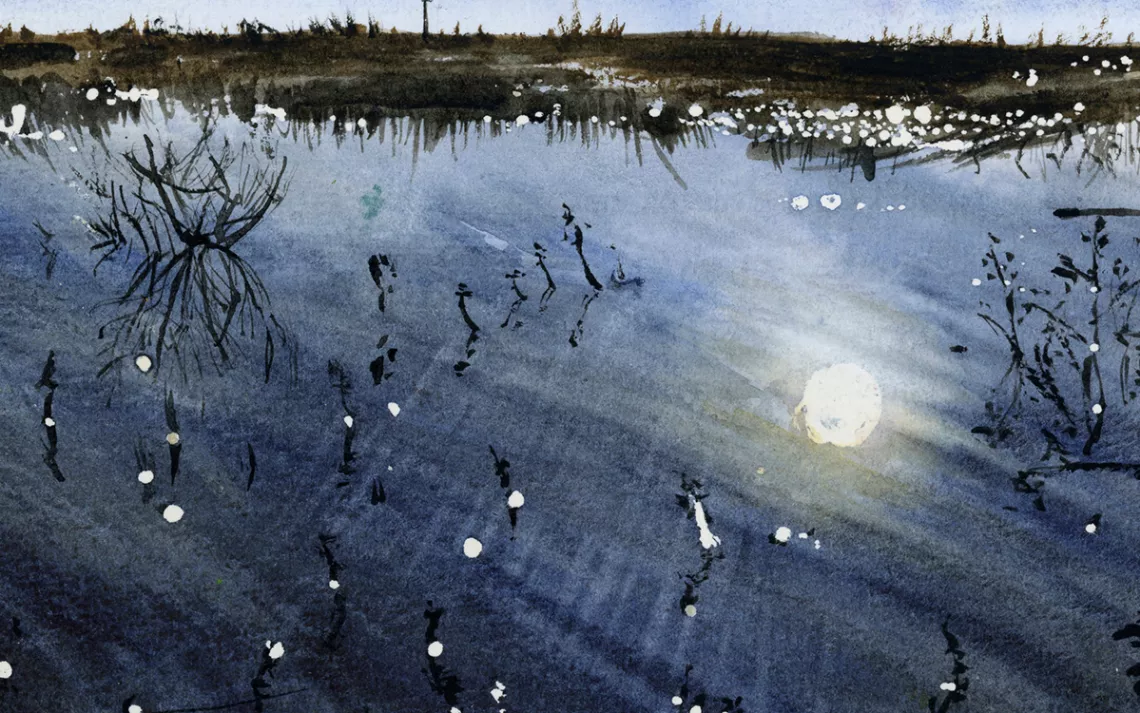

Illustration by Kate Golden

Recently, I decided to throw away all my old cancer drugs, a small mountain of orange-and-white plastic bottles. Cancer no longer deserved a whole shelf. It had been three years since the diagnosis, a year and a half since my last chemo treatment, six months since I started sleeping again. I was a healthy person, not a patient. All I needed now was tamoxifen and a few vitamins. These drugs weren’t my life anymore. Why did I hang onto them for so long?

The answer was, like chemo itself, a nasty cocktail: one part fear of recurrence and one part worry about where the drugs would end up.

Fresh out of treatment, I was being practical. Maybe a quarter of these drugs were anticancer therapies I had abandoned because of the side effects, but the rest were all my aunties—the pills I took to address the side effects of the cancer drugs. Anti-diarrhea, anti-constipation, anti-heartburn, anti-nausea, anti-vertigo. Two needles filled with a liquid that forced me into menopause. All the pills that failed to quell the hot flashes, or at least allow me to sleep through them. Some of them might come in handy.

Or not. As the shadow of recurrence receded, keeping them started to seem a tad implausible. Even though the cancer may lurk in my bones, where such vestiges are still my best and most morbid motivation for jogging. Also, the expiration dates were well in the past.

*

The pills could tell the whole story of what I had undergone. I was angry at them. This was easier than getting mad at doctors who were just trying to heal me (but failed to warn me about the side effects) or the drug companies that squeeze endless lists of "toxicities" into the tiniest of fine print, or the cold hand of fate that mutated my cells in all the wrong ways. I felt a strong urge to flush them all down the toilet. As everyone knows, flushing the toilet is an act of powerful magic that cleanses the soul. Things go away—they disappear from our lives, provided that they fit down the plumbing.

But there is no away, as I knew from all the stories I had written on wastewater systems. Catharsis has consequences. A problem you disappear, even just your unused birth-control pills, becomes someone else’s. And that someone may well be a frog or a fish.

*

Did it matter what I flushed now, though? I already had put so much dark matter down the drain. The safety protocol for chemo was that nurses didn’t touch me, for their safety, and neither should anyone else in the first day or two after infusions. The waste I produced at the hospital was closely regulated, but then I went home.

Carboplatin, one of my first chemo drugs, has the essence of world-destroying Shiva, compared to the well-mannered targeted drugs I got later. It binds its platinum complex to cells’ DNA, preventing them from replicating. It made things taste cancer-weird and attacked my marrow, causing copious nosebleeds and reducing me to a shadow of myself. In a 2021 review article of the effects of anti-cancer drugs on aquatic systems, platinum-complex drugs were ranked as the most toxic.

Endocrine-active drugs, which I will be on until my body stops trying to make the estrogen that feeds my cancer, were ranked number two. Docetaxel, another of my harsher chemo drugs, topped “most often detected in waterways.” The review included a map showing where cancer drugs had been detected in waters across the planet, but it placed a big question mark on the United States.

*

Twenty years ago, the US Geological Survey found 80 percent of the streams it tested had some drugs in them. But just knowing they’re in there doesn’t tell you how much to worry. Say a pharmaceutical makes it through wastewater treatment, as many of them do—these facilities were not designed to handle pharmaceuticals. That triggers a long chain of questions: What is the half-life of this drug? How much is there? What happens to creatures that encounter it? Does it affect their survival? Their reproductive success? Coming at the problem from the other end is just as tricky: Many weird, bad things are happening to aquatic ecosystems, but how much, if any of it, can be blamed on our drugs?

Being human is bad for the environment: No shortage of evidence there. As a cancer patient, I felt like walking medical waste. I idly wondered whether my body’s chemical residues should cause me to reconsider my personal disposal plan of burial at sea. I wanted to feed the crabs that fed me, but crustaceans are particularly sensitive.

What happens to pills that go into med drops, anyway? Out of a sense of responsibility or curiosity, you may try to find out where your waste really goes—but collectively we have done an incredible job of setting up our systems so it is much easier not to. The State of California’s medical waste management website was geared more for those who had medical waste to throw away, and less for those concerned about wherever away was. Eventually, I learned that pharmaceuticals are incinerated, whether they come from hospitals or homes—but it happens somewhere outside California, because the state forbids such incineration of its own waste due to air-quality concerns. (Incinerators used to be one of the state’s biggest emitters of dioxins, which, unhelpfully, cause more cancer.) So what’s in the ash, and where does it go?

“I’ve never thought about where the ash goes,” said an employee at the state’s medical-waste-management program, gamely trying to answer my questions on a Friday afternoon. “I’m certain that it’s disposed of responsibly, though.”

*

Wherever the ash went, it had to be better than the toilet. I took my pills down to my cancer clinic’s pharmacy, where I had seen a drop box. A sign pasted onto its front demanded that I remove all personal information from the bottles.

I tried peeling up one label, failed, looked at my pile, got angry again, and considered setting the whole bag on fire. I thought of the fumes, and the guilty feelings that would result.

The pharmacist saw me and mentioned casually that the chain of handlers was pretty tightly controlled. I shoved the bottles into the med drop like I was force-feeding it. It took three batches. No satisfying swirl, but it would have to do. The pharmacist glanced up. He’d seen this ritual before.

“I get it,” he said, kindly. “You want them out of your life.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club