When Fossil Fuel Money Talks, the DNC Listens

The DNC drew a bright line against oil money. Then Tom Perez smudged it out.

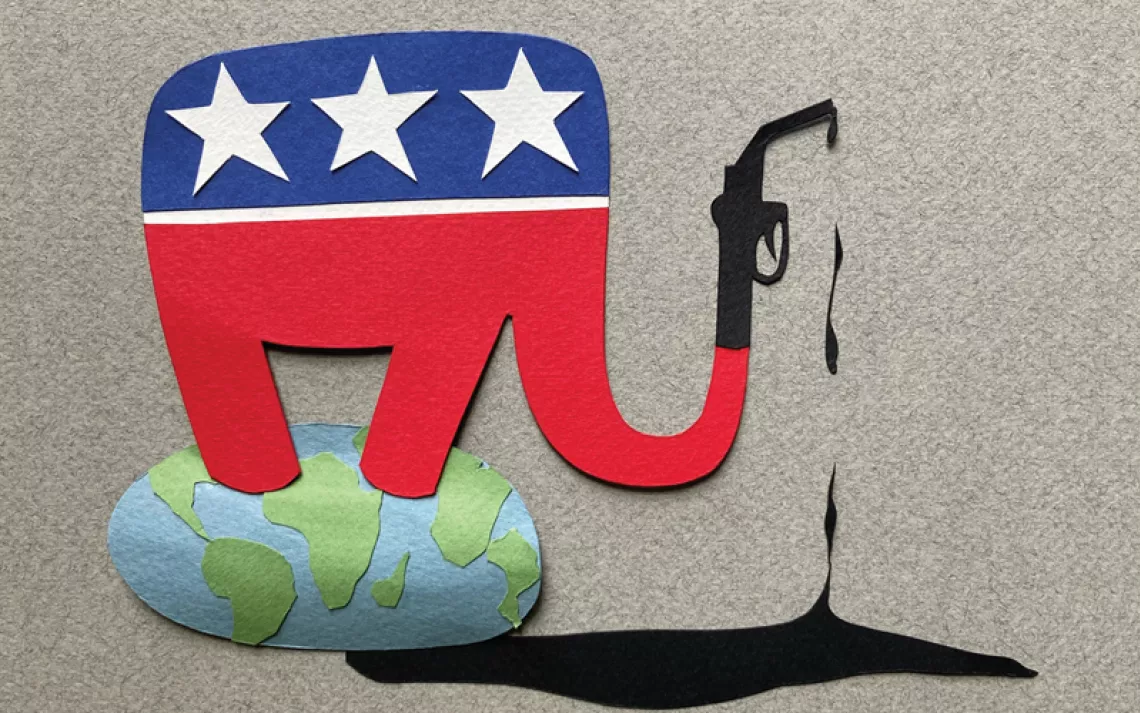

Photos by StudioRoma-biz/johnnylemonseed/iStock

Leadership, famously, requires making tough choices. Real leaders know that decisions are rarely easy and often mean prioritizing one competing interest over another and, in the process, making a statement of values.

This summer, the Democratic Party leadership faced just this sort of difficult decision involving the party’s approach to global climate change and money-in-politics. Unfortunately, the party’s leaders chose poorly.

The executive committee of the Democratic National Committee passed a resolution last week stating that the party “gratefully acknowledges and will continue to welcome” political contributions from workers in the energy industry and their “employers’ political action committees.” Or, more simply, the DNC will continue to accept donations from companies such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Peabody Coal that are systematically burning down the planet. The resolution also appears to affirm the party’s support for an “all-of-the-above energy economy”—code for saying that coal, oil, and gas should be considered equal to wind, solar, and smart hydropower.

Grassroots environmentalists, progressive-minded party insiders, and some members of Congress have responded with a mix of righteous anger and genuine confusion. “I am just furious,” RL Miller, founder of Climate Hawks Vote, a grassroots political action committee that pushes candidates to take aggressive stances on climate change, told me. “I don’t have anything good to say.” On Wednesday, dozens of young climate activists with the Sunrise Movement protested outside the DNC headquarters in Washington, D.C. In the last few years, the Sunrise Movement has spearheaded a national movement that has succeeded in getting more than 900 political candidates to pledge not to take any fossil fuel corporation donations. “Which side are you on now? Which side are you on?” Sunrise Movement activists chanted, as some held a banner reading “No Fossil Fuel Money.”

For Congressman Raúl Grijalva, a progressive stalwart from Arizona who is the ranking member of the House Natural Resources Committee, the DNC resolution is just plain “weird” and “a mistake.” “I was terribly disappointed,” Grijalva told me, and then went on to say that the decision will make it harder to demonstrate to voters that the party believes climate change is a top priority. “It doesn’t make sense, because you have to provide a sharp difference to the American people. And that sharp difference is that we, as Democrats, accept climate change and man’s role in climate change and the fossil fuel industry’s role in climate change.”

The resolution was especially galling since it marked the reversal of a policy banning fossil fuel donations that the DNC approved just two months ago. At a June meeting in Providence, Rhode Island, the DNC’s executive committee voted to stop taking campaign contributions from fossil fuel corporations. That resolution—which was sponsored by Christine Pelosi, a veteran party activist and daughter of the House minority leader—described climate change as an “existential threat to civilization” and declared that “fossil fuel corporations are drowning our democracy in a tidal wave of dark oily money.” The measure passed unanimously.

So maybe it’s more accurate to describe the policy reversal as a rout—one that took place under the cover of a Friday afternoon in the dog days of August. The new resolution, sponsored by DNC chairman Tom Perez, was sprung on the executive committee members at 10 A.M. on August 10, giving them just four hours to review it before a scheduled 2 P.M. conference call. In a lengthy conversation this week, Pelosi told me that she was given no warning what was coming. “We got a notice for a telephonic executive committee meeting, but they didn’t say what it was for,” she said. “I kept saying, ‘What is this meeting about? What’s on the agenda?’ And they didn’t tell us. I mention that because the process on this oil money was as closed as the process on my [original] resolution was open. I spent months on mine. But on this, it was completely hide-the-ball.”

During the Friday afternoon conference call, Pelosi moved to strike what she considered the most offensive part of the resolution, the mention of “employer political action committees.” “There’s no such thing as ‘employer political action committees’ in the FEC [Federal Election Commission] code—they are corporate political action committees,” she told me. Pelosi’s amendment was voted down 28 to 4. The resolution ultimately passed on a vote of 30 to 2, with just Pelosi and one other executive committee member, Garry Shay of California, dissenting. “It was clear the fix was in,” Pelosi told me.

Which raises the obvious question: What is the new resolution intended to fix? On a call after the vote, DNC chair Perez said that some in organized labor had expressed concerns about the ban on fossil fuel industry donations, which he characterized as “an attack on working people in these [fossil fuel] industries.” “We’re not a party that punishes workers simply on how they make ends meet,” Perez, who served as labor secretary in the Obama administration, went on to say.

The notion that the original ban on fossil fuel industry contributions was somehow anti-labor is nonsense, Pelosi and others say. The June resolution made no mention of shutting out small-dollar donations from rank-and-file workers. And, more to the point, if some unions felt attacked by the original resolution, then they should have shared their concerns in the open instead of engaging in backroom politics. “I had heard some vague rumors that labor wanted a do-over,” Miller of Climate Hawks Vote told me. “To which I let it be known that I was happy for a very public discussion on whether the DNC should be taking money from fossil fuel industries. But nothing ever happened.”

“Nobody is demeaning the role of organized labor, now or in the future, and for the fossil fuel industry, primarily the big corporations, to use the workers as a cleavage point to get the DNC to back off is, I think, really hypocritical,” Representative Grijalva told me. “I wish the leadership of the DNC had pushed back to find a middle ground, because I think most of organized labor understands climate change is an important issue.”

Yet instead of trying to find that middle ground (another hallmark of leadership), Perez decided to steamroll greens. The Democratic Party leadership has gone from allegedly attacking energy workers to quite obviously insulting those who are passionate about sustaining a livable planet. The party has pivoted, at least on paper, from aspiring to create enough “renewable energy to power every home in the country” back to an “all-of-the-above energy economy” that shrinks from any choices at all. Pelosi sought to draw a bright line against the corrupting influence of fossil fuel monies; Tom Perez smudged it right out.

(The DNC press office did not respond to a detailed list of questions I sent via email.)

I’m no Democratic Party partisan (my allegiances are to wild nature and the health and welfare of human communities), but this whole saga is demoralizing. Two central pillars of the progressive movement are in an unnecessary internecine tussle. Grassroots environmentalists who expect the Democratic Party to, well, lead on climate are worried that there’s a leadership vacuum at the top. Meanwhile, political donations from the fossil fuel corporations continue to flow overwhelmingly to Republicans. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, almost 90 percent of the oil and gas industry’s contributions go to the GOP, and so far during the 2018 election cycle, energy and natural resource industries have given a scant $238,000 to the Democratic Party. “For $238,000, it’s not worth it,” Grijalva told me.

I’m sure the Koch brothers are laughing all the way to their nearest petcoke pile.

Perhaps the most distressing part of the DNC’s decision to prioritize the bruised feelings of some labor unions over the necessity of taking bold action on climate change is that it’s fundamentally a false choice. There are, to be sure, real tensions between labor and greens—most obviously, how to manage a shift away from fossil fuels without tossing workers over the side of the lifeboat. And, at the same time, those tensions are not irreconcilable. From what I can see, the environmental movement is fully committed to creating a “just transition." That is, ensuring that the clean energy economy is built by union workers who earn family-sustaining jobs. “We have to reject the false choice between the economy and the environment,” Pelosi told me.

You’ve probably seen the old bumper sticker “There Are No Jobs on a Dead Planet.” If that sounds a bit too tie-dyed, consider this—that’s exactly what the director-general of the International Labour Organization recently told Time magazine. Smart, forward-looking labor leaders recognize that the path to collective prosperity on a hot and crowded planet runs straight through the renewable energy economy. The fact that the DNC leadership can’t see that truth seems, to me at least, a stunning case of political myopia.

Tom Perez and the DNC leadership sought to avoid having a hard, honest conversation about balancing the interests of workers with the imperative to turn away from the fossil fuel economy. They thought they could shrink from standing up to Big Oil and King Coal. In doing so, they have delayed, by some small measure, action to address climate change and its accompanying heat waves, fires, and storms—all of which narrow the choices left to the rest of us.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club