When Black Women Walk, Things Change

Morgan Dixon talks walking, radical self-care, and Harriet Tubman

Vanessa Garrison and Morgan Dixon | Photo courtesy of GirlTrek

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence,” wrote Audre Lorde. “It is self-preservation.” Lorde was speaking to a problem that has particular weight for African American women—because they are so often expected to take care of other people in a culture that gives them few resources to do so, they suffer disproportionately from stress-related diseases.

More than a decade ago, two college friends, Morgan Dixon and Vanessa Garrison, made a compact to take care of themselves and to protect each other from these pitfalls. Over time, that compact widened to include thousands of women and became GirlTrek, the largest nonprofit focused on the health of black women in the country.

We featured a short profile of Morgan Dixon in our March/April 2018 print magazine. Here is the extended interview.

Sierra: When you were growing up, what was your relationship to health and fitness?

Morgan Dixon: We didn’t call it health and fitness, but I played outside every day. My family went to the roller skating rink. My mom walked to work. We played kickball at our family reunion. We just didn’t call it exercise.

Do you feel lucky that this was modeled for you, even if it wasn’t labeled in that way?

No, I think it’s generational. I would argue that most of my friends and family, and most of the women I know regardless of race or income led just a more active life 30 years ago. I attribute that to lifestyle shifts in America in general. Since then we’ve had incredible shifts in culture due to policy change, due to work expectations and because of economic inequality. I think people are working more. I think families are broken for a lot of reasons, institutional and otherwise. I think our families are different and our communities are different.

How did you meet Vanessa?

She was at UCLA and I was at the University of Southern California—USC. We were both the first person in our families to graduate from a university. We had to work full-time, so we were working at an investment banking firm in Century City, which is kind of like downtown Beverly Hills. I think we were there 10 A.M. to 8 P.M. every day, then went to school before 10 A.M. and on the weekends.

So you guys were busy.

Yep, yep, yep. We bonded quickly because we needed friendship and support. And we had lots in common. Like we both like Tupac. We both like Nikki Giovanni poems.

We both went to school in California and then decided to move to Atlanta because we were cool. Vanessa went to Atlanta to work for the record label SoSo Def. I taught at South Atlanta High School for Teach for America.

But the first job I had in Atlanta wasn’t Teach for America. It was as a park ranger at the [Martin Luther] King Center. I did tours of his birth home, on his block where he grew up, in his father’s church where he preached. I had the total head-to-toe like green hat and everything—buckle, shoes—everything ranger.

What was that like?

It was not the way to catch your husband. But it was fantastic. I joke with my mom that she must have really prayed because my job every day was to sit in Ebenezer Baptist Church and hear Dr. King’s sermons play over and over through a crackly speaker. I was like, “What did you do, Mom? Why is my job sitting at church?”

It’s sad because our national parks—particularly our urban parks—are not always visited in the way they should be. So I would have a lot of down time with Dr. King.

Did that have an impact on you?

Of course it did. I don’t know anyone who can sit in Ebenezer Baptist Church where Dr. King preached and listen to his voice day in and day out and not be affected by it. We call our training The Mountaintop, because I’ve heard the Mountaintop speech no less than 375,000 times. So we take women to Rocky Mountain National Park, with the YMCA. We take them on sometimes their first really serious hike, up to an alpine lake as a kind of training ground—a couple of days of training, but we call that whole experience “The Mountaintop.” That no doubt has to do with that. But I was already interested in civil rights and movement building. I was a girl scout until I was in the 12th grade. I think Juliette Low was a movement builder. Yes, I was affected by Dr. King, I was also affected by scouting, by the outdoors, by my own family’s civil rights history.

How did you and Vanessa first start talking about health and fitness?

After college, we both jumped into our careers. She was working at CNN, and I started with Teach for America. We both got married. We had lots and lots of responsibilities beyond our immediate families, both of us.

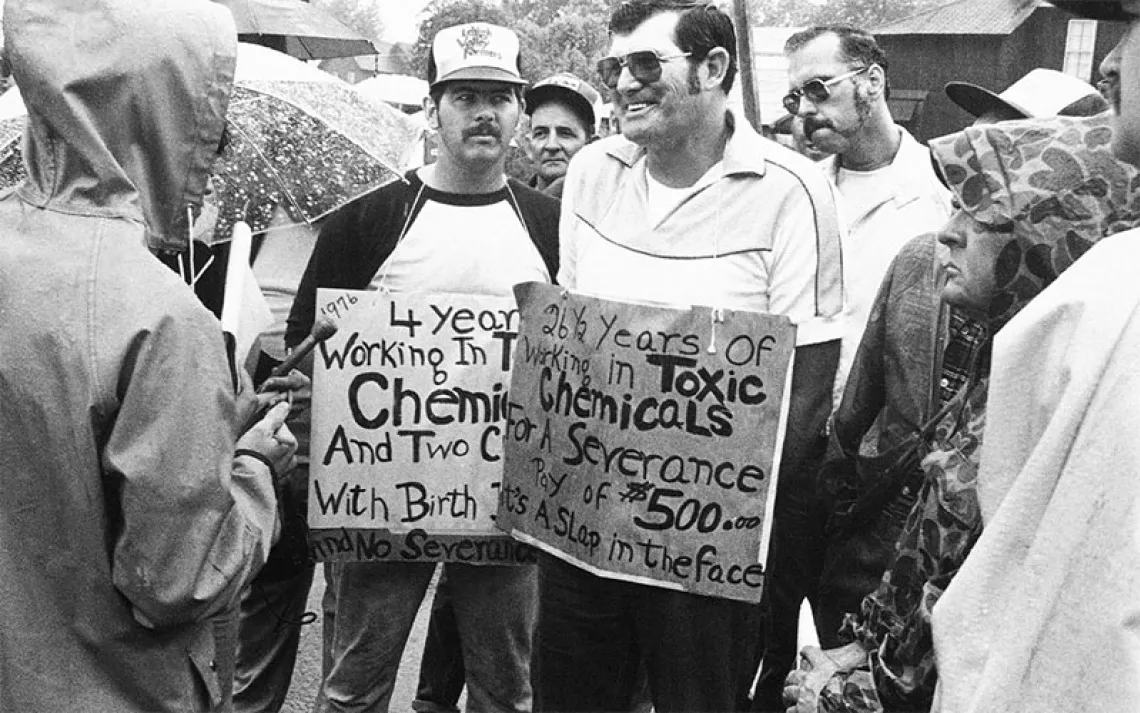

We were working really hard at our jobs, like many women. But we didn’t really see a reprieve. In fact we saw a trend of what was honestly a death sentence for a lot of women we loved—where service to others is championed over caring for oneself. They had incredibly stressful, high-labor lifestyles, and they just worked themselves to death.

We actually celebrate that in our communities—this kind of martyrdom. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the movie Soul Food, but everyone’s around mama’s bed at the end, she’s dying, and it’s an emotional end. She’s diabetic. She had cooked these wonderful soul food dinners every Sunday. She had become the glue of the family that was falling apart. I don’t find any sentimentality in that. I think that for far too long, too many black women have been dying early deaths.

For example, Fannie Lou Hamer. On October 6, we are doing Fannie Lou Hamer’s 100th birthday. She started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. She’s a civil rights icon, and she registered 60,000 people to vote in Mississippi. She died at 59 from heart disease and other obesity-related complications. She was beaten in prison. She’s this archetype of putting your body on the line for those you care about. That comes from a long, complicated history, and it is still something we do.

Vanessa and I started talking about it on a very, very personal level. We were two friends trying to hold each other accountable to not falling into those pitfalls. We tried every day to make a point to slow down and practice this radical mindfulness that went against everything the momentum of life was telling us—going against the judgment of others that we were kind of self-serving—that we were lucky that we could go on vacation or that we were lucky that we could go for a hike on the weekend, or eat fresh fruits and vegetables because we had more resources. That kind of thing.

Remember, just a generation before us, our parents were farmers. Fresh fruits and vegetables are not foreign to our culture. Fresh air and sunshine is not foreign to African American culture. It’s just that because of what had happened in the '60s, '70s, and '80s in this country, we’ve gotten farther and farther away from that.

Once Vanessa and I got a taste of what healthy living looked and felt like, the more we wanted other people to come with us. We initially started this hiking club with girls in Bridgeport, Connecticut. That’s why we’re called GirlTrek. We had these amazing fifth-grade girls—I would take them hiking on the Pequonnock Trail and kept talking to Vanessa about it. It was making a big difference in their lives. But it wasn’t going to be transformative for the lives of all those women who were disproportionately suffering under the weight of obesity-related disease and chronic health problems.

So we talked and we tried a bunch of things and both decided, “What if we rallied their moms? What if we didn’t just rally their moms but a critical mass of their moms? What if a million black women started to walk every single day as a radical act of self-care? Just 30 minutes a day of meditation, prayer, walking, exercise outdoors—as therapy, as demonstration, as collective action, as sister talk?

When black women walk, things change. We talk about that all the time. It’s the title of our TED Talk, and it’s true. When women are walking and talking together, shit is about to go down. We started to invite our friends. We started using our email lists and said, “Hey, can you guys walk with us?”

We started blogging every day. We started posting things that inspired us on a Facebook page called “Healthy Black Women and Girls.” Before we knew it, we had more followers on social media than Michelle Obama and Susan G. Komen. We were like, “Oh! There’s a need for this.” Today we are 100,00-plus women who have committed to walking in their neighborhoods with us, for us. Our goal is to get to a million, and we’re on track for that. We’ve doubled in size from this time last year.

It sounds like Harriet Tubman is a very inspirational figure for GirlTrek.

I think she was a badass environmentalist. I said that one time in front of a crowd that I won’t name. Very elite outdoor trip folks—it wasn’t the Sierra Club—and they laughed. I don’t know if they were uncomfortable. I don’t know if they didn’t know who Harriet Tubman was. I give them a lot of latitude around why. But her ability to navigate through open woods, to carry a group to safety, to know different plants and fauna, to know river crossings. . . . There’s a famous quote of hers. When she crossed the Mason-Dixon line, she said, “I looked at my hands, and there’s a glory over everything.”

I am obsessed with her because she is folkloric in many ways, but she is so human. Yes, she was a social reformer. Yes, she was an abolitionist, and fighter, and military genius. And, she was very connected to the outdoors. She was also an incredible speaker, which took a kind of daily courage that’s different from running from dogs, or starry nights and dark woods. Sometimes, courage looks like having conversations with people who are different and have different opinions. That felt just as courageous in her life, and pretty under-reported.

I am a 40-year-old black woman. And I have been living in fear my entire life. I had Klan dreams when I was a kid. Audre Lourde wrote that she learned fear with her mother’s milk. So when we talk about the woods and cultural relativism, let’s keep in mind what the woods represented for people. I have felt afraid for many years of my life, I really have. I’m just not afraid anymore. The way you live is the way you win. You understand where your power lies, and you understand what is changeable and what is not changeable.

When I think about our current administration, when I think about global warming, those things are very real, but I also know that Donald Trump is no Bull Connor. I know that we have seen darker days and we have overcome darker days. We have overcome this before. We have vowed to protect our forest. We have vowed to protect our home. We have rallied to show love over hate. We’ve done these things, and who are we to not have hope after people have seen and won these battles before.

I’m not afraid. In fact, I am activated. In fact, I am awake or woke. I feel like for the first time in my lifetime, people who have had the luxury of not feeling hyper-aware are now awake too, and that feels good.

What are some changes you’ve seen in women participating in GirlTrek?

We just held something called a Stress Protest where women came together to relax and connect with nature. This was the weekend after the storm in Houston and there were I think 11 women who flew in from Houston and two of their houses were underwater.

Some of them came up and spoke in front of the whole group. They were saying that coming together in common cause at this time was the only thing that felt tenable. When we are feeling more and more isolated, more and more divided, more and more distrustful, it is the time to draw closer together to really double down on our values. We’re working with them to do some kind of restoration and philanthropy in support of our sisters in Houston.

I was sitting in a meeting with all these government stakeholders. All the usual suspects were there—the health department, the YMCA—everybody was there at this stakeholder meeting led by the government. Somebody asked the question: “Getting a million women walking is one thing, but how do you turn that into advocacy? What is your move for advocacy?”

I gave a real politic answer. I was like, “We’re working with Stanford University. We’re training women to do walkability audits to change the built environment.” Everybody was like, “That’s so great!” And then one of the GirlTrek women, Susie Page, raised her hand. They said, “We’re not taking questions,” but she was like, “No, I just have one thing to add.”

Susie is the caretaker of her mom, who I think is the oldest Trekker—Grandma Nan might be 93 now. I think they have four generations of family in about five or six cities who walk with GirlTrek. Susie stood up and said, “There was a blighted lot right next to our church. It had an absentee landlord and graffiti everywhere. We kept making calls, and nobody would do anything about it. So now every single first Saturday my team started cleaning up the lot. We didn’t ask for permission. It’s beautiful. We’re thinking of planting a garden.” She got a standing ovation.

For me, slowing down, walking at human pace every single day—just practicing that level of mindfulness gives me perspective, instead of the rapid feed of news and all that other stuff that makes me anxious. It gives me the ability to hope.

Tell me about the walking audits that you train people to do.

When you get a million women walking, you need other capacities, right? We identified what else needs to happen for those women to start walking, continue walking, and lead their healthiest, most fulfilled lives.

What happens is women train for several months with Stanford on how to use their walking audit tool, and they walk through their community and they audit the needs of their community. If there needs to be a crosswalk here, if there’s not enough tree cover for you to have shade to walk, if there are trash cans. They take that data, and Stanford helps us compile that into community reports that we can then do community planning around. We bring together civic leaders and citizens, and they rank what are the most important issues, and then they share out with their city or representatives, in New Orleans in the Ninth ward, in Baltimore, in Philadelphia, in Denver.

We have GirlTrekU—our advanced public health training. We train women to stand on the front lines of what we call disease disruption—everything from changing the big infrastructure of communities to increasing access to free public health classes. We partner with the American Council on Exercise to teach fitness instructors, so we are pipelining our women into becoming fitness instructors with ACE. We have instructors teaching mental health first-aid like it was CPR to people all over the country.

What was it like to meet Michelle Obama?

One thing you should know is that Vanessa and I are CEO and COO of the largest health nonprofit in the country for black women, but before that we are really good girlfriends. We were laughing so hard, because neither one of us knew what to wear. We wanted to wear like our Sunday best, like our nylons and pearls when we were with Michelle. We were just all flustered—“Is our hair right? Are we perfect?” Because Michelle Obama was literally perfect in person. Like perfect. Like more perfect than TV.

I said, “There are hardly no black people in here. She is going to see us. Do not take pictures.” As soon as she came out, we started taking pictures. She is stunning, she is radiant, everything you would imagine. She’s so smart. We’ve seen her in a bunch of contexts now. We are involved with Partnerships for a Healthier America, which is an initiative that she started with corporations. She’s doing just incredible work.

Do you have a fun biographical story about you and Vanessa to share?

One time we got into a fight because a reporter had put somewhere—I don’t even remember what they said. They either said I’m the brains and Vanessa is the heart or Vanessa is the brains and I am the heart. And we argued so hard. I said, “No, I’m the brains!”

When we were just starting to get on our health game, we wanted to set an ambitious goal. We had never done races of any kind, but Vanessa was like, “Well I’m going to do a half marathon!” I did outdoor leadership training at the National Outdoor Leadership School—a 50-mile backpacking trip.

I did a 50-mile backpacking trip, and when it came time to do her half marathon, she was like, “Are you going to come?” I was running so slow, and she was like, “Is that how you run?” She finished way before me. There was this group of ladies that were much older than me. They beat me.

But the pictures of me backpacking, and Vanessa sweaty coming across the finish line—they were really instrumental in our circle of friends. They said, “Oh we want to get involved! We want to do things like that!"

I said, “Well, first we start walking.”

This interview has been condensed and edited by Heather Smith.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club