What Does It Mean to Restore Bears Ears, in Words and in Spirit?

The Biden administration can improve upon our most unprecedented monument

Bears Ears National Monument | Photos by Jon Bailey

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Sierra Club.

One of the lessons of the Trump era, taught mostly through negative example, is that words matter. What we call people affects how we treat people. This is also true for the land—what we call a place affects how it is treated.

Bears Ears National Monument—the 1.35 million acres of rugged and beautiful land in southeast Utah declared by President Obama in 2016 and reduced by 85 percent a year later by President Trump in US history’s largest public lands protection downsizing—has been called many names over the years, including Hoon’Naqvut, Shash Jaa’, Kwiyagatu Nukavachi, and Ansh An Lashokdiwe. The words are different for various tribal nations, but the meaning is the same: Bears Ears. Two distinctive orange buttes that really do look like ears rise up above a meadow where Indigenous people from far and near have come to meet and trade for centuries.

As the only national monument to grow out of the thinking, planning, and advocacy of Native Americans, Bears Ears National Monument was unprecedented. The redemptive nomination of Deb Haaland as the first Indigenous secretary of the interior, and the first Native American to hold any cabinet-level position, comes at a crucial moment in our nation’s relationship with its more than 450 million acres of public lands. What’s more, on the very first night of his presidency, Joe Biden ordered federal agencies to reverse any of Trump’s executive actions considered “harmful to public health, damaging to the environment, unsupported by the best available science, or otherwise not in the national interest.” Bears Ears was specifically mentioned under that order, and early signals point to its full restoration. My hope is that its good name, too, will be restored.

The summer after the reduction, I met with James Adakai, president of the Oljato Chapter of the Navajo Nation and a Bears Ears commissioner, in the tiny town of Bluff, Utah, on the edge of Bears Ears. We sat at a picnic table not far from the San Juan River, and he told me about all the work that went into the creation of the Bears Ears National Monument proposal and the thinking that went into its name.

He pointed west toward Bears Ears, a landmark that you can see from a surprising number of places in the Four Corners.

“Those are sacred ancestral hills,” he began. “For thousands of years, our ancestors drew strength from them. The minerals, the vegetation, the woods, the birds, all the traditional uses. In Navajo it is a way of life. We want to teach that way to future generations. That’s what Bears Ears is all about.”

Though the Bears Ears Coalition was made up of five tribes, Adakai reiterated what I had already learned: that it was the Navajo who began the work, through the grassroots group Utah Diné Bikéyah.

“Diné Bikéyah did the cultural mapping of the area. They also did interviews of 80 elders. The cultural knowledge of the elders, their historical knowledge, was immense, and it wasn’t easy to collect. So that contradicts one of the assumptions about the Bears Ears proposal: that it came up overnight. There was a huge effort put into the research and the planning.”

It was after this initial work that Diné Bikéyah reached out to other tribal nations. “The Hopi and Zuni because of the rock art and Anasazi ruins,” Adakai said. “The Ute Mountain Ute, who have historically used the land and still have a piece of land east of Bears Ears. And also of course the Utes who had historical ties. So that formed the Inter-Tribal Coalition.”

It was after this initial work that Diné Bikéyah reached out to other tribal nations. “The Hopi and Zuni because of the rock art and Anasazi ruins,” Adakai said. “The Ute Mountain Ute, who have historically used the land and still have a piece of land east of Bears Ears. And also of course the Utes who had historical ties. So that formed the Inter-Tribal Coalition.”

Since each of the five tribes had names for the twin buttes of Bears Ears, all meaning, roughly, “bears ears,” the coalition concluded that the English name was best, to show unity and to avoid conflict among tribes.

Then along came Trump and Zinke. They not only massively reduced the monument but also chopped it into two unconnected, renamed sections: They called the southern section, that contains the Bears Ears buttes, by its Navajo name, Shash Jáa, and the northern section by its long-time local name: Indian Creek.

Despite the coalition’s efforts toward healing and unity, the new names spoke to division, disunity. Something historic was created with Bears Ears after much time, work, and thought. And then in no time and with little work, it was decided that that thing should be destroyed. Does it really matter whether it was done out of ignorance, or with the calloused thought of cynicism?

To James Adakai it mattered.

“They are trying to split us up,” he told me. “Trump is setting tribe against tribe. He is dividing and renaming the monument in a way that messes with the tribes. Trying to disunite. It is an insult to us.”

* * *

Bears Ears is many things, including an attempt at correcting history. The first national monument was Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, proclaimed in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt. Its almost 900-foot-tall granite monolith, made famous in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, had long been called Bears Lodge by the Plains Indians and was considered sacred by many tribes. Which means that in “saving” it, the United States government also claimed it. This usurpation of sacred ground would be repeated again and again in the creation of parks and monuments; places of ceremony and cultural import were claimed in the name of recreation, conservation, and science.

The years since have seen some incremental movement toward tribes becoming more actively involved in the management and administration of national monuments and parks. A precedent for the creation of Bears Ears was set in 1951, when the Grand Portage Band of Minnesota Chippewa and Minnesota Chippewa Tribe asked that tribal land be recognized as a national monument, thus creating Grand Portage National Monument in Northern Minnesota.

More recently, the Ogala Sioux have assumed administration of the South Unit of Badlands National Park in South Dakota. Not far from Bears Ears, Canyon de Chelly National Monument is effectively comanaged by the National Park Service and the Navajo Nation. While the Park Service takes care of park and visitor services, the Navajo Nation manages the land and resources, including mineral rights. But studies have characterized the relationship between the Navajo Nation and the Park Service as historically “turbulent.”

Bears Ears was to take this a step further, but in at least one way, its original proclamation fell short. The coalition and its backers wanted true comanagement by the tribes and the government. Obama’s proclamation almost got there but not quite, stating that the secretary of agriculture and the secretary of the interior would manage the monument through the US Forest Service and the BLM, while a Bears Ears Commission, made up of a member from each of the five tribes that brought forth the original proposal, would “provide guidance and recommendations.”

Guidance and partnering are fine; actual authority and comanagement would have been so much better. The hope is that Secretary Haaland and President Biden will understand this and not just restore but improve Bears Ears.

* * *

Here is another way that words matter when it comes to how we treat the land. The Trump un-declaration of Bears Ears was a short, peremptory missive—an order, basically—as blunt and unpoetic as the man who signed the document. The difference between that proclamation and the original proclamation of Bears Ears speaks worlds.

National monuments are created solely through the decree of the president, according to the 1906 Antiquities Act’s directive to preserve “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures.” That is why we say national monuments are “declared,” and why they are declared through proclamations. Originally these proclamations were direct and concise, much like the Antiquities Act itself. This started to change with the Carter administration but really changed under Bill Clinton, whose proclamation for the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument grew out of the work of several Clinton aides and Utah scientists. “The Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument’s vast and austere landscape embraces a spectacular array of scientific and historic resources,” its proclamation begins. “This high, rugged, and remote region, where bold plateaus and multi-hued cliffs run for distances that defy human perspective, was the last place in the continental United States to be mapped.”

The Grand Staircase–Escalante proclamation paints a complete picture of the landscape—its geology, paleontology, archaeology, flora, and fauna. The proclamation also approaches the level of literature. It makes the point repeatedly that “the rugged canyon country of the upper Paria Canyon system, major components of the White and Vermilion Cliffs and associated benches, and the Kaiparowits Plateau” are scientifically and historically vital for the United States and therefore fit the criteria laid out by the Antiquities Act.

But it also tells a good story.

The Bears Ears proclamation outdoes it. Drawing heavily on the original proposal written by the Inter-Tribal Coalition, and then tweaked and refined by Interior Secretary Sally Jewell and the acting chair of Obama’s Council on Environmental Quality Christy Goldfuss, it describes the land thoroughly and at times even poetically.

How many government documents contain sentences like these? “From earth to sky, the region is unsurpassed in wonders. The star-filled nights and natural quiet of the Bears Ears area transport visitors to an earlier eon. Against an absolutely black night sky, our galaxy and others more distant leap into view. As one of the most intact and least roaded areas in the contiguous United States, Bears Ears has that rare and arresting quality of deafening silence.”

The proclamation tells the story of Bears Ears, down to its black-tailed jackrabbits and sacred datura plants and alcove columbines. It is an American story of place that includes the first Americans, along with archaeology, anthropology, natural history, and even the phenology of the place. In it we learn that “numerous seeps provide year-round water and support delicate hanging gardens, moisture-loving plants, and relict species such as Douglas fir.” It also tells of the human beings who inhabited the place, beginning with the Clovis people who “hunted among the cliffs and canyons of Cedar Mesa as early as 13,000 years ago,” and moving through the Ancestral Puebloans who built their rock homes there, to the Native farmers and Navajos who came later.

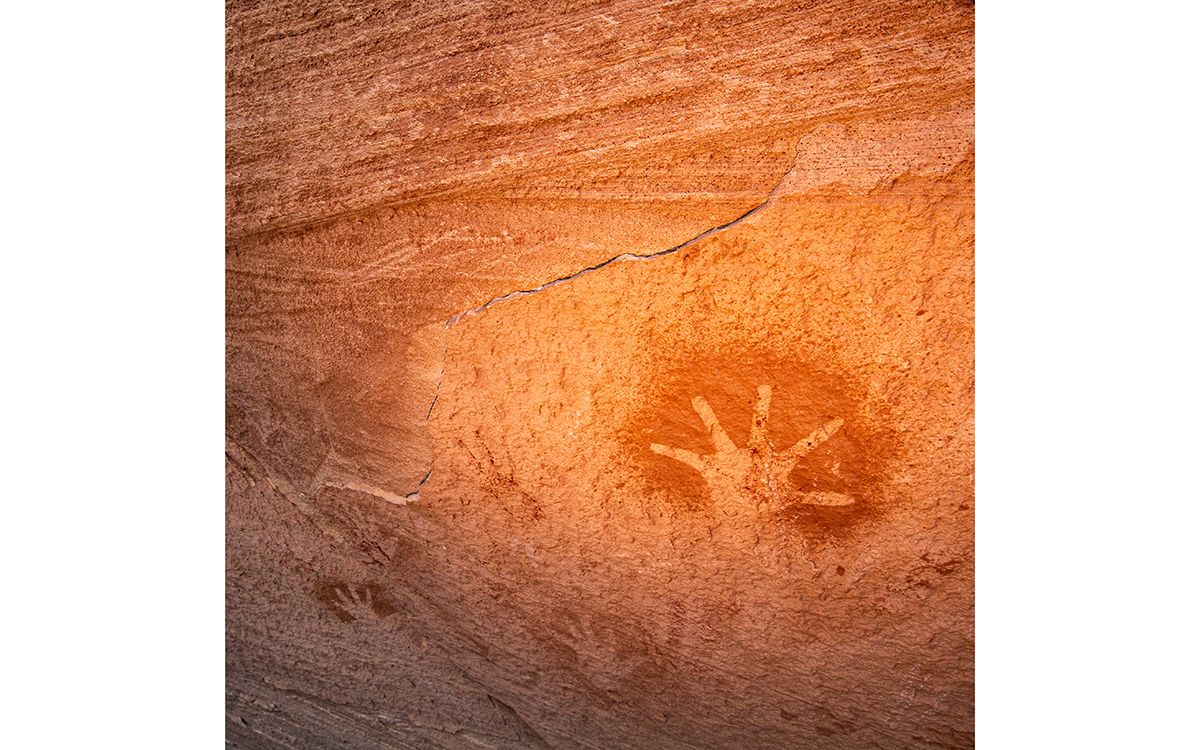

The proclamation document/prose poem goes on: “The landscape is a milieu of the accessible and observable together with the inaccessible and hidden. The area's petroglyphs and pictographs capture the imagination with images dating back at least 5,000 years and spanning a range of styles and traditions. From life-size ghostlike figures that defy categorization, to the more literal depictions of bighorn sheep, birds, and lizards, these drawings enable us to feel the humanity of these ancient artists.”

A key concluding sentence effectively connects Native knowledge of the place to chief directives of the Antiquities Act: “The traditional ecological knowledge amassed by the Native Americans whose ancestors inhabited this region, passed down from generation to generation, offers critical insight into the historic and scientific significance of the area.”

Western values of science and study—values that led to the creation of the Antiquities Act—are not ignored, but a different way of knowing is put on the same plane. This is radical. This is new. This is a possible confluence. This traditional way of understanding the land is not just a way of knowing. It, too, is something that the act must defend. “Such knowledge is, itself, a resource to be protected and used in understanding and managing this landscape sustainably for generations to come.”

The document also brings natural and human history into the present. “The area's cultural importance to Native American tribes continues to this day. As they have for generations, these tribes and their members come here for ceremonies and to visit sacred sites. Throughout the region, many landscape features, such as Comb Ridge, the San Juan River, and Cedar Mesa, are closely tied to Native stories of creation, danger, protection, and healing.”

The Bears Ears proclamation takes what was best about the monument ideal—setting land aside from development and protecting wildlife—and melds it with something better. To read the original document proclaiming Bears Ears a national monument is to feel hope. And now we are poised, with Joe Biden as president and the nomination of Secretary Haaland, to not just restore the original promise and good name of Bears Ears, but to take what was strong and make it stronger.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club