Two Cheers for California’s Fracking Ban

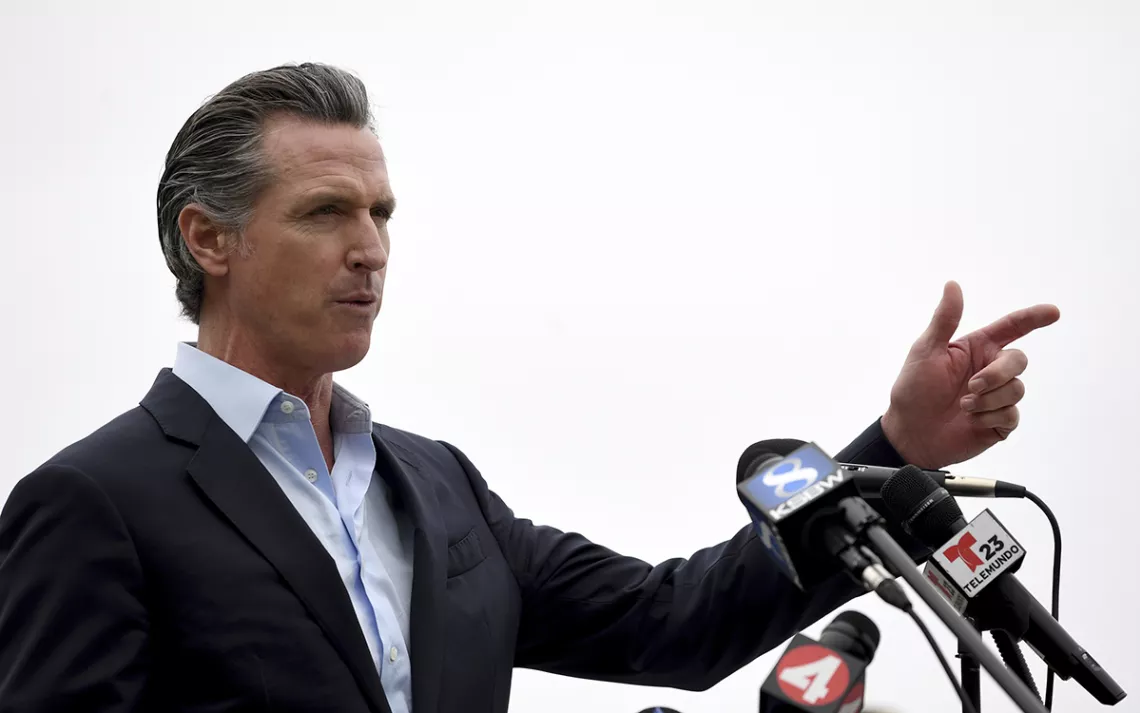

Gavin Newsom did what no other oil-state governor has—but more is needed

Photo by AP Photo/Nic Coury

Last Friday, when California governor Gavin Newsom directed state regulators to begin a process of ending new permits for hydrofracturing in 2024, it seemed like reason for environmentalists to celebrate. With a recall effort threatening Newsom’s job and a pandemic still raging throughout the state, moving to restrain the state’s influential oil industry is clearly an act of political courage.

But, as the governor himself noted, fracking—which in California means shoving huge amounts of water laced with sand and chemicals into oil-bearing rock formations—accounts for only 2 percent of the state’s oil production. And even that may overstate just how little oil Newsom’s directive will leave in the ground.

What’s more, it takes only a few days to frack a new reservoir, after which oil can flow unimpeded for the next 20 years. By the time the proposed fracking ban kicks in three years from now, most of the rock that traps the state’s recoverable oil will already have been propped open, freeing vast pools of crude that can be drawn up for decades. That’s why the proportion of fracked oil in the state has declined from 20 percent in 2015 (according to a state-ordered report) to 2 percent now: Before the California Geologic Energy Management division (CalGEM) imposed new fracking regulations in 2016, “well stimulation was more common,” CalGEM said in an emailed statement. So in the two-year period between the passage of Senate Bill 4, a 2015 law to regulate fracking, and the law’s regs taking effect, drillers got their fracking out of the way.

Newsom also took the significant step of calling on CalGEM to “evaluate how to phase out oil extraction by 2045.” That may be slower and less decisive than environmentalists would like, but it signals an intention that no other governor of an oil-producing state has dared to set. California is an environmental trailblazer, and to see a governor address the supply side of climate mitigation—not just consuming less oil but phasing out extraction—can give other officials at home and abroad the courage to follow. In that way, says Kassie Siegel, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Center, Newsom’s announcement “is a really big deal. For decades, limits on fossil fuel production have been the missing piece of climate policy. It's the most fundamental thing we need to do.”

But, she adds, California oil poses many other dangers to the climate and public health beyond fracking. Monica Mariko Embrey, associate director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Dirty Fuels campaign, agrees. “If the effort is to ban the most dangerous types of extreme oil extraction in California,” she says, “fracking is just one of many different types that really need to be phased out as soon as possible to protect the health of our communities and our climate.”

Embrey says she’s “encouraged” that the governor chose to take on oil in this fraught political landscape, “but the timeline [of his directive] is too long and the scope too narrow.” If Newsom wants to mobilize his progressive base to come out for him against the recall, she says, he needs to step up his game. “What's glaringly missing from Friday's announcement,” she says, “was a justice and equity component that protects the communities”—most of them Latino and lower-income—“who are currently bearing the brunt of our fossil fuel production.”

Just a week before Newsom’s announcement, a far broader phase-out of California oil production failed to clear the state senate’s Committee on Natural Resources. Senate Bill 467, introduced by state senators Scott Wiener and Monique Limón, would have ended fracking permits after 2021 and banned it altogether by 2027. It would also have ended the more common and dangerous method of injecting high-pressure steam into wells. Steaming melts stubborn crude deposits into extractable liquid that can be drawn up by a conventional pumpjack, and California oil production depends on it to an astonishing degree: More than half of California’s oil wells require steam to manage their viscous crude.

Wiener and Limón’s bill would also have required 2,500-foot buffer zones between new oil and gas development and schools, homes, and hospitals. Such setbacks, or “health protection zones” as the bill called them, have been a top priority for environmental justice organizers around the state, who have documented how residents’ health deteriorates as oil production steps up in their neighborhoods. A new study, led by Jill Johnston of the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, associated “living nearby and downwind of urban oil and gas development sites” with reduced lung function.

Asked what was the one thing he would have asked Governor Newsom to salvage from SB 467, Kobi Naseck, coordinator for the environmental justice coalition VISIÓN, didn’t hesitate. “Setbacks,” he says. “No question about it.” He’s not unappreciative of Newsom’s new mandate to CalGEM, calling it a “historic moment” and a "huge win” for climate activists. But, he adds, “it doesn’t appear the governor is listening to frontline communities,” the people who live up against oil and gas facilities in California.

(Since 2019, CalGEM has supposedly been working on a variety of public health regulations, including setbacks. The results were due by the end of 2020, but CalGEM says the process has been delayed by COVID-19. A rulemaking was expected in April 2021; now it’s been pushed to mid-May.)

Roger Lin, climate and air counsel for the California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA), says that even if the governor’s announcement does result in a fracking ban, and phases out oil production by 2045, “that’s still 20-odd years from now.” But protecting public health and safety is something the governor’s office “has the constitutionally built-in authority” to do now.

Lin notes, however, a subtle but important effect of Newsom’s announcement: His proposed phase-out of oil production sets a new goal post for the upcoming re-evaluation of the state’s greenhouse-gas reduction mechanisms, something that happens every five years under the landmark climate law that then-governor Jerry Brown signed in 2006. It was something proponents of shuttering the state’s oil industry thought they were going to have to fight for, and now it’s on the table.

“It's just up to us to keep up the pressure to make sure that it actually happens,” VISIÓN’s Naseck says, “and on a quicker timeline.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club