These Lands Belong to You and Me

Our federal public lands, including parks and monuments, are a collective treasure

Detroit youths enjoy an ICO (Inspiring Connections Outdoors) trip to Yosemite National Park. | Photo by Eliza Earle

“There are so many people in Detroit; there's so many people in Chicago; there's so many people in Atlanta and Washington, DC, and Cleveland and LA who don't realize that whatever is ailing them potentially could be cured by a visit to a place like this.”

Those are the words of Yosemite National Park ranger Shelton Johnson. Johnson is a renowned advocate for diversity in our national parks. As a community engagement specialist for Yosemite, he sees it as his duty to connect people with nature and our national parks—especially people who, in their communities, maybe do not historically feel a connection to them.

Recently, Johnson welcomed a group of high school students from his hometown of Detroit—actually, from the same high school he attended, Cass Tech—on their first visit to Yosemite. They were with a trip organized by Detroit Outdoors and the Sierra Club.

“You own this. This is your property,” Johnson told the students. “Yosemite is your property and your family's property. Yellowstone is your property and your family's property. The Grand Canyon is your property and your family's property. Any time you visit a national park, any ranger that you see, your taxes paid for that ranger. They work for you. Now, I never thought, growing up in Detroit, if I saw any guy with a badge that he worked for me.”

Ranger Johnson is right. America’s public lands belong to all of us. That goes for the more than 640 million acres of land that make up our more than 400 national parks, 560 national wildlife refuges, 154 national forests, more than 130 national monuments, and millions more publicly managed acres.

“Any time you visit a national park, any ranger that you see, your taxes paid for that ranger. They work for you.”

Diversity in our national parks is a tradition as old as the parks themselves. Decades before the National Park Service was created, the famed African American Buffalo Soldiers served as the first rangers for the country’s early national parks like Yosemite and Sequoia. (Ranger Johnson happens to be an expert on that topic.)

Making our national parks accessible to more people and communities is an act of patriotism and love. Kids like the group from Detroit and millions of others like them in cities across the country deserve the transformative experience had by those Cass Tech students in Yosemite: hiking among the majestic rock formations and expansive meadows of Yosemite Valley, finding peaceful sanctuary among the placid lakes and serene landscapes of Tuolumne Meadows.

Our national parks are part of America’s identity, gifts to us to enjoy and use to connect with nature in a profound way. But our parks and other public lands are more. They are a means of fighting both the extinction emergency and climate crises. They protect wildlife and critical ecosystems. They clean our air with their trees and remove carbon dioxide from our atmosphere.

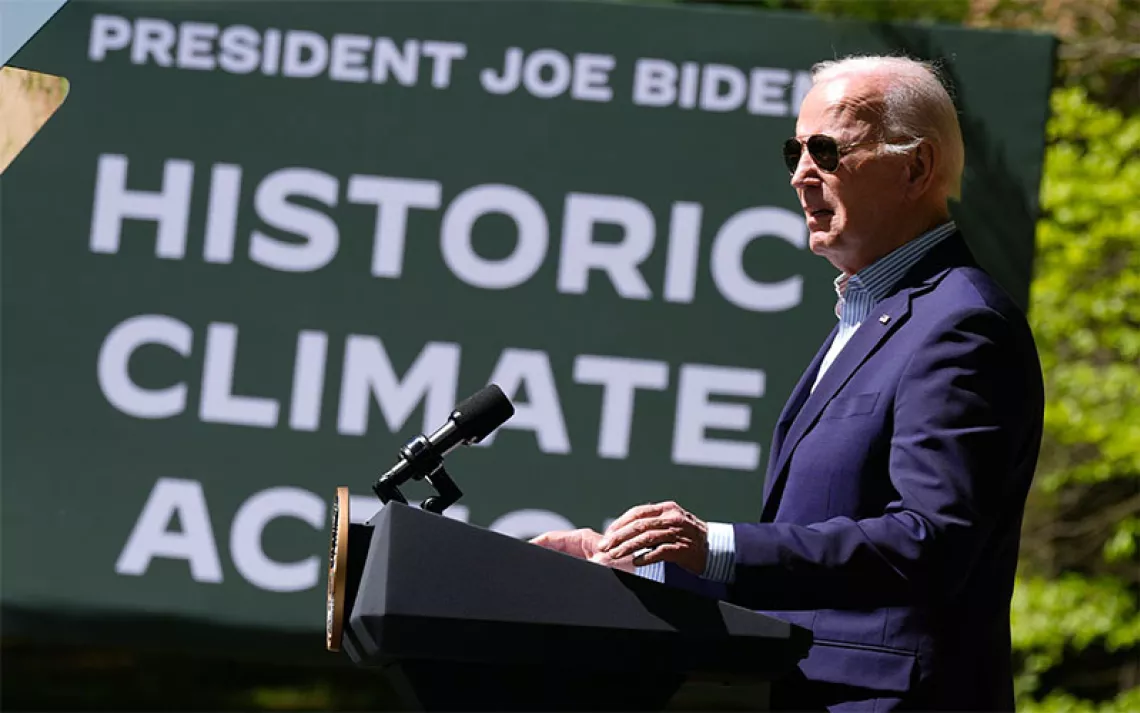

The Biden-Harris administration has advanced initiatives that recognize this. A new public lands rule from April recalibrated the Bureau of Land Management’s mandate from having a nearly exclusive focus on resource extraction to giving equal weight to conservation. And the US Forest Service just concluded a public comment period on a proposed plan that could protect the country’s remaining old-growth forests. Mature and old-growth trees have a unique ability to absorb and store carbon pollution, making them one of nature's most powerful climate solutions. This is near and dear to my heart. The first protest I ever organized was when I was a high-schooler and helped pull together an anti-clearcutting rally in Sacramento, California.

National Park ranger Shelton Johnson celebrates the legacy of the Buffalo soldiers with Detroit youths during an ICO (Inspiring Connections Outdoors) trip to Yosemite National Park. | Photo by Eliza Earle

There are boundless examples of why protecting public lands is so important. I recently visited the Western Arctic in Alaska where an effort to add so-called Special Areas would preserve millions of acres of public lands in one of the last untouched ecosystems in the United States. It would safeguard a vital habitat for imperiled species and help protect the Arctic from the devastation of fossil fuel extraction. I am convinced that witnessing the migratory paths of caribou and the ancient stone fences of the Inupiat people would drive home for anyone the urgency of protecting our planet and conserving wildlife and wild places.

And our national monuments recognize sites of not only natural but historical and cultural importance. Our newest national monument—designated by President Biden in August—commemorates the 1908 Springfield Race Riot that sparked the creation of the NAACP, a national reckoning with racial violence, and birth of the modern civil rights movement.

Last week, we celebrated National Public Lands Day. Let us use the opportunity to break down lines of race, income, and geography when it comes to enjoying America’s public lands.

As Ranger Johnson told those kids from Detroit, one of the reasons he was so excited to see them was because by simply being there, they were “changing the whole sociological dynamic right now, just being present.” He told them, “That's why it's powerful that you're here. Because this is a sign of change, and this is what the future looks like. You are the future.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club