The Sinking Cities and Rising Seas of (Near) Future Tomorrow

It's time to start thinking about life in a different world, says author Jeff Goodell

Many melt ponds on sea ice north of Greenland, as seen during an Operation IceBridge flight on July 24, 2017. | Photo courtesy of NASA/Nathan Kurtz

In a chance encounter, author and climate journalist Jeff Goodell found himself standing face-to-face with a man he had been trying to interview for months: billionaire Miami developer Jorge Pérez. Goodell was attending an art show at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, named after the developer, and Pérez happened to be there. “I’m standing in line and there he is,” Goodell says. “Being a journalist, I couldn’t help but walk up there and start talking to him.”

At the time, Goodell was reporting for his new book, The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World (Little Brown, October 2017), a potent examination not of whether seas will rise in our lifetimes, but of the fact that they will rise, how fast it could happen, and how coastal cities around the world are poised to drown. Miami is the epicenter of that story.

Pérez is known as the “Trump of the Tropics.” The development business he cofounded, Related Group, is the biggest builder in Miami, responsible for the construction of one out of every five condos there. Goodell was eager to ask him about sea-level rise, and whether he was concerned about how it would affect his real estate holdings.

“No, I am not worried about that,” Pérez told Goodell. “I believe that in 20 or 30 years, someone is going to find a solution for this.” Then, Pérez said, “Besides, by that time, I’ll be dead, so what does it matter?”

The encounter, which exposes a disturbing kind of new climate nihilism, is just an example of the many revelatory stories that make The Water Will Come one of the most important books of the year. While the terms of the climate debate often get misleadingly framed as a polarity, especially as defined by President Donald Trump and his surrogates—real or hoax—Goodell has illuminated a far more complex gray area. The facts of rising sea levels and the consequences thereof are already clear to political, military, and business leaders alike. The story behind why they fail to act in the face of that reality isn’t simply about whether they believe or not. It has as much to do with the all-too-human reflex to rationalize our actions, and a woeful inability to grasp the full import of those actions in a temporal world, as it does climate denial, or even greed. Meanwhile, as the lucidity of a changing planet gathers starker focus, for some, a quiet resignation has begun to settle in.

Jeff Goodell spoke with Sierra about his book, the COP23 climate conference now wrapping up in Bonn, and his views about where we’re headed as a planet in an age of climate change.

*

Sierra: You make the case in The Water Will Come that what matters more than the height the seas rise is the rate at which they rise. What is it that you want people to understand about this distinction?

Jeff Goodell: A lot of people think of sea-level rise, in fact I did for a long time, as an incremental thing—something that sort of had this nice smooth sloping curve, a few inches a decade maybe, that would gradually increase over time. I always thought of it as one of those things that was off on the horizon. It wasn’t until Hurricane Sandy and my dawning awareness of this power of water and the implications of sea-level rise that I learned differently about it. One of the fundamental truths that I came to understand in reporting the book is that in geologic history, it’s pretty clear that sea-level rise has risen in these pulses, not in a smooth curve. That’s one of the reasons why scientists right now are so concerned about west Antarctica, because of the potential for ice-cliff collapse there, and the fact that a whole lot of ice could go into the water really fast. In fact, west Antarctica might have been one of the triggers in the past for dramatic sea-level rise.

If we think of sea-level rise as a gradual problem, then it’s easy to deal with, or it’s easier to deal with: we can make decisions about elevating buildings, about moving away from coastlines. We can have a rational way of thinking about it. If, however, sea level comes in pulses—there’s evidence in the past of as much as 13 feet of sea-level rise in a century—if we get a dramatic pulse of sea-level rise, then the implications for coastal cities around the world are huge. Even a foot or two of fast sea-level rise, by fast I mean in a decade or two, would be enormously devastating for virtually every low-lying coastal city in the world. It takes a long time to build infrastructure, it takes a long time to make the political decisions about how to protect ourselves from rising seas. But if this has to play out immediately, then there basically is nothing that can be done beyond putting up sandbags, which is not exactly a defense strategy.

When the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its fifth and most recent report in 2013, it projected three feet of sea-level rise on the high end of possibility—which ended up serving as a basis for decision-makers at the 2015 climate negotiations in Paris. But you write in the book that those findings were already out of date by the time the report came out, as it did not include studies of the big melt in Greenland the year before. Instead, some experts now project as much as three, six, even nine feet of sea-level rise by 2100. What would the impacts be?

The latest NOAA study this past January had seven feet as the high end, and the National Climate Assessment that just came out said there was a risk of as much as eight feet in this century. One of the things that’s happening is that scientists understand ice dynamics better, and it becomes clearer and clearer that we are not cutting carbon emissions at anywhere near the rate we need to. The NOAA numbers from the late '90s were two or three feet. These numbers are only going one direction, so the risks are becoming greater and greater.

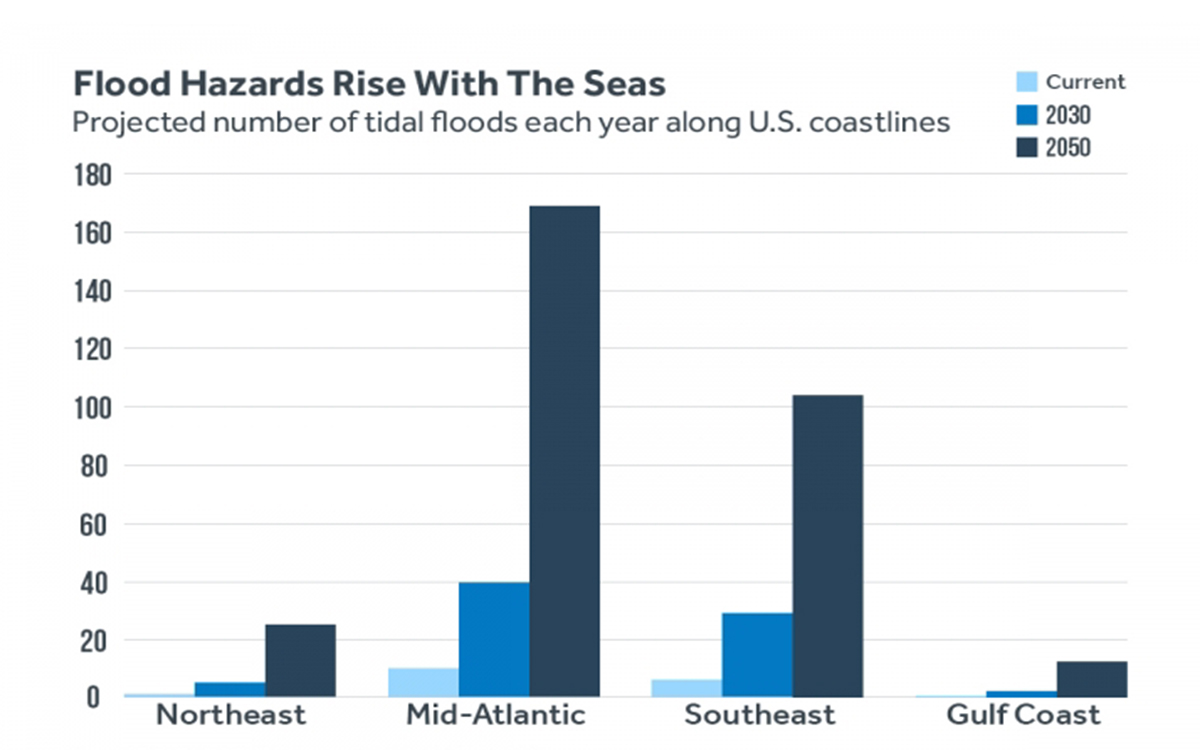

As to the consequences, every place is different. Certainly cities like Seattle are in better shape than a city like Miami. But even a modest amount of sea-level rise—like two to three feet, which is the low end of what we’re thinking about and could easily happen by 2060—would have enormous economic consequences for places like Norfolk, Miami, New York, Boston, all these cities with low-lying development, because the cost of trying to defend shoreline, to build sea walls, protect roads from erosion, relocate roads, is huge.

At the same time, you’re going to have radical devaluation of property values, because nobody is going to want to buy a place where we know the sea is coming up and the flooding is only going to get worse over time. It’s very obvious that there’s going to be a big real estate crash in these coastal areas. That’s going to hit government property tax revenues really hard, so state and local governments will have a harder time paying to rebuild infrastructure. It becomes this downward spiral.

Then there’s the ecosystem. Two or three feet of sea level would basically transform the Everglades into a marine environment. The whole ecosystem of the Everglades would be completely destroyed. And that’s just one example. Coastal swamplands in North Carolina, where I am right now, would be hugely impacted. All kinds of animal life would be affected, everything from alligators to nesting turtles. Two to three feet is massive beach erosion on all coastlines. Even in places where the risks are not obvious. I was just in Half Moon Bay, near San Francisco, at the Ritz Cartlon Hotel, where I happened to be for a conference. It’s on a high cliff, so it’s not exactly at risk for flooding, but the rising sea is eating away at the cliff and the cliff is eroding, and the hotel could go into the water. The value of that hotel is rapidly heading downhill toward zero in real time right now because of what the seas are doing to the cliffs there. So, it’s hard to overstate the consequences.

Courtesy of Little Brown and Co. | From The Water Will Come by Jeff Goodell

That speaks to a point you raise in the book about why we’ve been so slow to realize the gravity of the situation. You write that we as a species can’t really absorb scenarios of this breadth, that we are poorly designed to grasp the scope of a situation like this.

We view the world through our own experience. We go to the beach and we look at the beach and we think this is where the beach is and this is where the land is, this is where the sea is, and we think that’s more or less a hard line. Not only can we not always be thinking about ancient time and Pangaea and continents drifting around and all that, but we don’t normally think about beaches as temporal arrangements of sand that move all the time. So we build all kinds of infrastructure on our coastlines with this idea that this line between water and land is defined, because that’s how we see it, but in fact, in nature, it’s a very loose and fluid boundary that over time changes radically. We’ve built all this infrastructure with this assumption that the way we see it is the way it will always be. What we’re about to discover is the risks and dangers of that.

I can’t tell you how many coastal roads I’ve walked on that are eroding away, houses that are falling off banks. The ocean is kind of this relentless attacking force on the coastlines, and as seas rise and storms get harder, that force is only going to get stronger and more profound.

Were you surprised by what Jorge Pérez told you when you asked him if he was concerned about the impact rising sea levels will have on his business empire?

In retrospect, I kind of respect him for what he said. He didn’t bullshit. He basically said, "I don’t care about this. I don’t think about this. It’s not my problem." On one level, that’s incredibly inhuman of him to not care about future generations, to not care about how his work carries into the future. But in a strictly capitalist sense of "my job is to build the buildings that people want and to sell them and build more." . . . You know, you can’t ask a lizard to go ride a horse. That’s sort of what that was about: This is who I am. I am the lizard that catches flies, and that’s my job, and I’m really good at it.

To talk about sea-level rise in Miami is to talk about real estate really, because Miami is a real estate engine, and that defines the economy of, and the gestalt in, Miami. I’d talked to a number of developers, some of whom spoke to me off the record and others who were more or less forthcoming or just weren’t that educated about it while others were basic deniers. They explained to me that for a person whose business it is to build a cool building that sells for a lot of money and then use that money to build more buildings, and that’s what you do for a living, there’s no reason to think about the long-term future.

You open The Water Will Come with a fictional vision of Miami underwater in 2037, in a prologue aptly titled “Atlantis.” What was your reaction as you watched Hurricane Irma flood the city?

It was surreal. It was like prophecy. I had written that opening a couple years earlier. It’s not like it was such a wild thing to imagine, but still, it just looked like exactly what I had written about in the book. It could well have been. It will be at some point. There’s an inevitability to a Category 5 hurricane hitting Miami. It’s just kind of a roulette game in terms of how long before that will happen.

Based upon what you know, what did you think about the fact that the U.S. delegation in Bonn this week made a presentation defending fossil fuels and the importance of coal?

The shamelessness with which they are answering to their fossil fuel daddies is unbelievable. Ultimately, this kind of clown show is damaging, because we’re in a race against a warming climate. As President Obama told me while we were in Alaska, this is one situation where there is such a thing as being too late. That’s the great risk here with what the Trump administration is doing: losing valuable time.

Your meeting with President Obama in Alaska is fascinating on many levels. The conversation, as you report in the book, brings into stark relief his approach—that of the gradual politicking of a climate pragmatist—and whether or not there’s even time for that at this point. The exigency of the issue is so clear, and here is someone who is so intelligent, so clearly immersed in the climate science, and yet he seems to surrender to the politicking required of his office, talking about how when he was a community organizer he learned that you have to knock on doors and build consensus and so forth. His approach doesn’t seem commensurate with the urgency of the situation. And yet at the same time, he also points out something very important, which is that if you just throw something like world hunger at people, they glaze over, and so how do you deal with that?

Yes, that’s the central paradox of my conversation with Obama, which is his understanding the urgency and the need for action and the climate science very well, but having a practical mindset of how to go about it. That defines him as a politician. Unfortunately, we can’t run a double-blind experiment where we do it his way and my way and see which one works better.

I don’t know if he’s right. No one knows. He did a lot in his second term for climate. He set the world up very well for the next step. If he would’ve led marches in the streets. . . . I don’t know if that’s something he’s capable of doing. That’s partly the larger tragedy of this whole story. We should absolutely be out there in the streets and not taking any prisoners on this, but that’s not happening for many reasons that are pretty obvious: our lives being comfortable, the disruption of it, the disinformation out there about the risks.

I have tremendous respect for what Obama accomplished and for him as a man. Usually, when you talk to people like that, they want questions ahead of time and they want to know what you’re going to talk about. They did not ask for any of that. They just said, here’s the president. We’re closing the door. You guys have a good time, and we’ll be back in an hour and a half. It was extraordinary, because he had no idea what I was going to ask him about. I have a very good bullshit detector for people who understand climate science and climate change issues and climate politics and people who read notes about it. There’s a difference. And he really understood this stuff in nuanced ways.

But ultimately it’s depressing, because with Obama we had our best shot. We had a two-term president who was arguably one of the great presidents of our lifetime. And yet still, we’re in a situation right now where we just learned a few days ago that CO2 emissions are climbing again, up 2 percent after being flat for a couple of years. So we’re not even making incremental progress. We’re still going backward.

I have great hopes for innovation and solar panels and all that, but it’s hard. Ultimately, that’s why I wrote this book and called it, The Water Will Come, not The Water Will Come Unless Solar Panel Prices Drop Fast, or The Water Might Come. This is happening, and we have to think about living in a different world, and how we’re going to do that.

This book is a very sober analysis, coming from a journalist who has covered climate change for some time, and has covered related topics such as solar geoengineering and so forth. Given that you’ve interviewed so many people and have talked to scientists and world leaders, has this left you shaken? Not just as a journalist but as a human being—as someone getting clearer and clearer on the grim reality all of humanity now faces and talking to people who either don’t really understand what’s coming or don’t want to face it?

Here’s a weird and honest and interesting fact that happened to me in reporting this book: The book has made my life, and my experiences in Miami and other places I’m talking about in this story, better. I mean that in the sense of making them more vivid. It’s like the fact that you know and I know that we’re going to die at some point, that we only have so much time on the earth. There’s a moment when you start to be aware of your mortality and you realize you’re only going to see the sun rise X number of times, and you’re only going to be with your mother or your father or your daughter or your friends X number of times, so you damn well better pay attention.

That’s what this book has done for me. I walk on Miami Beach now and I realize that this place is not going to be here long. Obviously I’m sad about the stupidity of that. But I also walk around and look at it with a kind of appreciation and wonder, and I pay attention to things. It’s made my time in these places very vivid and very alive. I’m sorry that it all has to go, and that it will go. But, understanding and embracing change—and not thinking that just because we built something somewhere, or just because we were lucky enough to be born, we won’t ever die—is the central lesson to being human. I’ve gotten that from this book. It sounds weird, but it's true.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club