Ron Howard Depicts Life After the Camp Fire

“Rebuilding Paradise” emphasizes community resilience over corporate culpability

A home burns as the Camp Fire rages through Paradise, California, on November 8, 2018. | Photo by Noah Berger

|All photos courtesy of National Geographic

Shortly after the November 2018 Camp Fire tore through 153,335 acres and killed 84 people in Paradise, California, Ron Howard’s Imagine Documentaries team set out to capture the scorched aftermath. While most of us moved on to the next tragedy after mourning the most destructive wildfire in the US in the last century, Howard’s crew embedded in Paradise for a year to chronicle the struggle that persists long after a blaze fizzles out.

Premiering tonight at 8 P.M. central on National Geographic, Rebuilding Paradise follows a handful of characters who are dedicated to restoring the close-knit town, nestled in the Sierra Nevada foothills, to its former glory. As the fire’s destruction drives away longtime residents, former mayor Woody Culleton is shown saying he must help mend the community that supported him as he struggled with alcohol addiction. Meanwhile, Superintendent Michelle John is shown working tirelessly to send students back to class—in neighboring schools and rented mall spaces.

Steve "Woody" Culleton outside his newly rebuilt house. | Photo by Sarah Soquel Morhaim

Crew members were struck by how the subjects’ reactions closely aligned with documented cycles of grief—especially in observing the six-month “dip,” when residents came to terms with the disaster’s worsening psychological toll.

“There was no way of knowing what the personal story lines would be,” Howard told Sierra. “It really was an honest exploration, and we didn’t go in with an agenda … just our curiosity and a hope that we could build a bridge of empathy and understanding to our audiences.”

Rebuilding Paradise reveals many burdens that people consuming quick stories about the disaster may not have considered. In addition to destroying around 30,000 people’s homes, the Camp Fire tainted the town’s water supply with toxic chemicals like benzene, which can cause cancer.

In fact, massive wildfires may poison a community’s drinking water for years afterward. This hazard derailed Paradise school psychologist Carly Ingersoll’s plans to have a child—because she showers with local water, she can absorb benzene through her skin. “I have to put off that idea for a while or I have to move, and there’s nowhere to move,” Ingersoll says on camera.

The fire spared Ingersoll’s home, but the majority of Paradise lost theirs: Only 5 percent of Paradise structures remained standing. And few residents had the available funds to find stable housing elsewhere, given that the county poverty rate is nearly double the national average. Justin Cox, who then worked as the head Paradise school district custodian, used a federal loan to buy his family a trailer that he shuffled between friends’ driveways. Because they lacked renters’ insurance, the Coxes lost all of their belongings.

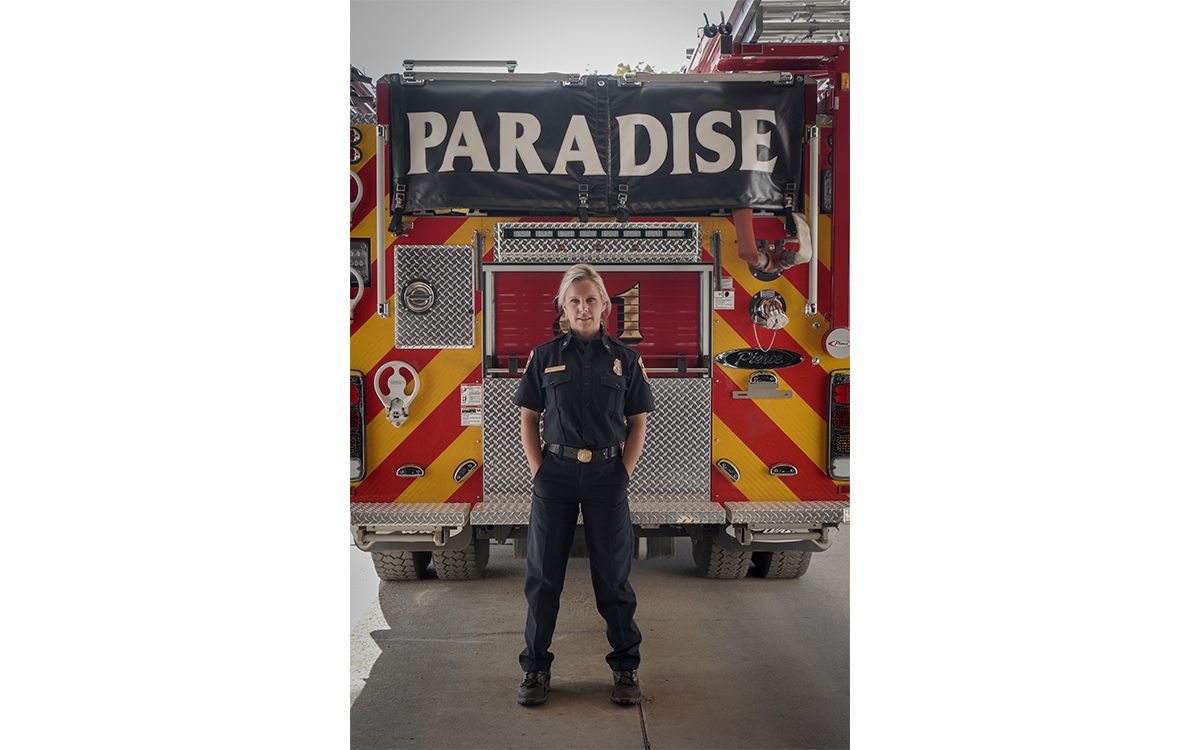

Shawna Powell, Cal Fire Northern Region Peer Support Battalion Chief | Photo by Sarah Soquel Morhaim

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. While Rebuilding Paradise begins with horrifying dashcam and cellphone footage documenting residents’ initial escape from an orange-tinted inferno, Howard later includes scenes of a community Christmas tree lighting and the former gold rush town’s annual Miss Golden Nugget parade. Still, these events are overshadowed by loss—the parade marches past a charred lot filled with workers wearing hazmat suits and gas masks. Surrounding hazard tape warns that the wreckage is contaminated with asbestos.

Throughout Rebuilding Paradise, viewers are reminded how climate change and forest mismanagement set the conditions for the unprecedented wildfires that now wipe out Western communities with alarming regularity. During a restoration meeting, pyrogeographer Zeke Lunder recommends prescribed burns throughout the West Coast to match the immense scale of the problem. But, he notes, “We can’t really vegetation-manage our way out of the problem.” (Two decades ago, Lunder coauthored a paper that noted Paradise’s particular vulnerability to wildfires.)

Howard also illustrates PG&E’s role in the deadly blaze: Its neglected transmission line ignited the Camp Fire, which spread up to 80 acres per minute due to drought conditions and hot, dry air.

Paradise residents don’t hold back in castigating PG&E, which filed for bankruptcy merely two months post Camp Fire. Legal clerk and environmental activist Erin Brockovich, who successfully sued PG&E for groundwater contamination in 1996, appears on film to condemn its utilities monopoly and urge survivors to hold the company accountable. Shortly afterward, PG&E executive Aaron Johnson faces a glaring crowd and outlines plans for future equipment inspections and entirely underground electric lines.

Audience members respond by demanding that the company pay for the massive overhaul and apologize to the families of the deceased. “I think they should have to come live here and see what people are going through,” Superintendent Michelle John says in the film. “They can take all this fricking dirt and burned-up cars away, but you’re still left behind with broken people.”

PG&E did ultimately face retribution: Last June, the company pleaded guilty to 84 counts of manslaughter in the Camp Fire case and agreed to pay a $3.5 million fine. And in a 2019 settlement, PG&E said it would shell out $13.5 billion to people who lost properties from its recent equipment-sparked wildfires. Yet half the money will likely take the form of company stocks, which have tumbled during the pandemic.

Make every day an Earth Day

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

As a director, Howard believes that it isn’t his role to impose blame or demand retribution for destructive wildfires—or for the broader consequences of a climate catastrophe wrought largely by the small group of corporations that foresaw our current crisis. Rather, he’s most interested in capturing the resilient characters of Paradise, who he says speak for themselves.

“If [a filmmaker] has a clear-cut vision that they want to put forward the way a columnist does, then the film can become a polemic where you’re making your point,” Howard told Sierra. “I didn’t come into this film with that. I just wanted to share what we observed.”

Ron Howard tips his hat to Steve "Woody" Culleton on Woody's property in Paradise. | Photo by Lincoln Else

Rebuilding Paradise may not intend to identify a villain, but its damning portrayal of PG&E is pointed. By focusing on a single town seemingly demolished by one company’s mistakes, the documentary obscures the fossil fuel industry’s culpability (and that of its investors) in exponentially magnifying greenhouse gas emissions with government support.

In the finale, a swift, terrifying montage flashes clips from other natural disasters intensified by climate change, like Hurricane Dorian, the Australian wildfires, and the floods that plagued Bangladesh. We can connect the dots, yet Rebuilding Paradise remains silent on the financial incentives that have allowed the world to burn.

It does, however, address the morality of reconstructing its titular community: As Woody Culleton shows off his newly repaired home, he wonders whether it’s “wrong” to remain in a fire zone, as so many others have done in hurricane-prone areas. Although Paradise is overwhelmingly white, this scene points to a broader systemic problem: Low-income people and communities of color are more likely to live in homes vulnerable to natural disasters, but are often less able to leave.

Rebuilding Paradise also recognizes Western wildfire survivors as some of the country’s first modern climate refugees. One resident, for instance, is depicted explaining that while he felt for the people of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, he never thought he’d personally experience a natural disaster.

In reality, the number of Americans vulnerable to the climate crisis continues to grow. “I don’t think any family is immune,” Howard told Sierra. “If you reach out to your extended family, somebody is going to live in a precarious place.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club