Raccoons Are Chipping Away at New York City’s Diamondback Terrapins

Biologists say raccoon predation is a leading reason for a sharp decline in one important nesting population

Pepper, a diamondback terrapin rescued from captivity, now lives at the Salt Marsh Nature Center in Brooklyn to educate people and students about the species and its threats. | Photo by Marlowe Starling

It was a warm July day in southern Brooklyn when local biologist Alex Kanonik went for a routine walk along the shoreline at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. Summer is diamondback terrapin nesting season, the best time of year to catch a glimpse of the state’s marble-faced turtles. But she instead stumbled upon a macabre sight: two female terrapins belly-up in the sand. One of them was Science Turtle, Kanonik’s social media star. Scattered around her were the shells of her hatchlings’ eggs.

Kanonik’s encounter was startling but not surprising. These gory murder scenes have become a more frequent sight at Jamaica Bay in recent years, and scientists largely attribute it to increased raccoon predation.

A population of raccoons thrive on the islands at Jamaica Bay, a wetland ecosystem situated in one of America’s most urban environments. These furry masked bandits can be cute—endearing even—but in many parts of the city, they are considered pests, prompting people to illegally relocate the varmints from the city streets to the wildlife refuge, where populations have flourished.

But they are pests in the wild too. Scientists at Hofstra University and the American Littoral Society have collected 23 years of data showing that a crucial population of diamondback terrapins, a native species, has declined at an annual rate of 2.6 percent at West Pond, a terrapin nesting spot on an island called Ruler’s Bar Hassock. Today, this population is less than half the size it was in 1998. Raccoons are largely to blame: On average, 97 percent of the terrapins’ deaths are owed to raccoon predation, said Kanonik, the Jamaica Bay program director at the American Littoral Society in New York.

“We're very concerned about every single adult animal that dies for any reason other than extreme old age,” said Russell Burke, a biologist who leads the Jamaica Bay Terrapin Research Project at Hofstra. Adult females are the most crucial because they contribute young turtles to the population, Burke explained. When raccoons dig up a nest, they dig up the entire nest—meaning no hatchlings will survive a raccoon attack. And they kill the maternal turtle too, by gutting her for any remaining eggs. “It’s just horrible to see,” he said.

Terrapins live in New York City's urban wetlands, like this one at Marine Park. | Photo by Marlowe Starling

Losing female turtles more frequently means serious trouble for the West Pond population. “When you're losing an adult female, you're losing 10 years of effort,” Kanonik said. “So it takes 10 years to recover a single female.” Scientists don’t have enough data to know the actual hatchling-to-adult survival rate for terrapins, but they expect about 1 or 2 percent to survive. With raccoon predation, that margin decreases even more. The average female terrapin will lay 12 to 14 eggs per clutch, Kanonik said, and up to three clutches each year. That means that out of three clutches—and with good odds—roughly one terrapin hatchling should survive to adulthood.

Kanonik and Burke said raccoons feed on up to 100 percent of terrapin nests some years, setting the population even further into a deficit. “When we find an adult terrapin that’s been killed by a raccoon, you know, this is really bad,” Burke said. Out of about 200 to 300 females, even a 5 percent loss in a single year sets the population into a decline, he explained. “That’s years’ worth of potential growth already gone,” he said. “That’s the sort of thing that sends populations into downward spirals.”

Raccoons aren’t new predators, Burke added, but there was once a time when Jamaica Bay was free of them. As a human-altered wetland, it isn’t a completely natural environment, but raccoons weren’t a threat to terrapins 50 years ago when the area was named a national park. When Burke’s team started the terrapin research project in 1998, they came across an occasional dead terrapin with the belly-up signature of a raccoon mining for eggs. But over time, he said, the one or two raccoons who first developed this behavior taught the technique to other raccoons. Now, predation appears to be rampant, in part because the population has grown and spread to many of the wetland’s islands. (Yes, raccoons can swim.)

Alex Kanonik lays out male and female terrapins on a dock after they were discovered in an abandoned crab trap in 2017. The incident prompted a statewide order requiring crab traps to have turtle excluder devices: small rectangular openings that prevent terrapins from entering the cage. | Photo by Don Riepe

Biologists like Burke and Kanonik say raccoon management would help protect terrapins, but the National Park Service—which oversees Jamaica Bay’s wildlife management—has not agreed to kill or remove raccoons. “If you pay more attention to species that are rare, and less attention to species that are dirt common, then you could argue that returning the park to what it was like in the ’70s is a good thing,” Burke said. One management idea, he says, would be to adopt feral cat control methods that sterilize the animal without harming it.

But removing raccoons from Ruler’s Bar or sterilizing them wouldn’t be much help, said Patti Rafferty, chief of resource stewardship at Gateway National Recreation Area, which includes the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. The raccoons at West Pond are not an isolated population, she said, because it’s adjacent to areas with more raccoons. By contrast, New York City’s sterilization program for deer on Staten Island has been successful because the population is isolated: No deer in, no deer out. With that in mind, the Park Service is discussing future raccoon management in partnership with NYC Audubon to target marsh islands, where more isolated populations of raccoons are threatening wetland birds by eating their eggs too.

Raccoons aren’t the only terrapin predators. People still poach terrapins for their meat. Other turtles get tangled up in nets or illegal crab traps. The biggest recent effort to protect New York’s terrapins came after one incident in 2017, when Kanonik and her colleagues at the American Littoral Society discovered an overflowing crab trap full of half-dead terrapins. It sparked outrage in the conservation community and prompted a statewide law requiring anglers to fit their crab traps with turtle excluder devices: small rectangular gates big enough for crabs to enter but small enough to prevent terrapins from entering so they don’t get stuck inside and drown.

Biologist Alex Kanonik found “Science Turtle” dead from raccoon predation this summer at West Pond between scattered showers, when nesting females like to come ashore. She found the female turtle's microchip nearby in the sand. | Photo by Alex Kanonik

While excluder devices help, terrapins aren’t formally protected at the state level, meaning there isn’t legislation to enforce conservation measures for them in New York. Across the river, however, New Jersey’s terrapins are listed as a species of concern. Still, there are some protections for New York’s turtles: It’s illegal to harvest, possess, or otherwise tamper with any reptiles or amphibians. Plus, local conservation organizations have named terrapins a species of “special interest,” granting them more attention from state and federal agencies. Commercial harvests used to be legal too, until overharvesting eventually prompted an administrative order to end commercial terrapin harvests early in 2016. And on the national scale, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species lists the terrapin as vulnerable because of its overall decreasing population trend along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, from Massachusetts down to the tip of Florida and up to Texas.

But it wasn’t always this way. There was once a time when terrapins were abundant in the US. In the early 1900s, diamondback terrapins abounded—so much so that terrapin farms were commonplace along the Eastern Seaboard. From Maryland to Georgia, people relished terrapin soup, a delicacy popularized by former president William Howard Taft, who was said to have hired a private chef for that particular dish. With the beginning of the Great Depression came the end of terrapin farming, a business too pricey to sustain (although turtle soup remained on menus across the Southeast for a few more decades).

Beyond predation, climate change also threatens terrapins. The sex of turtle hatchlings is determined by how warm the sand is around a nest. Sand temperatures higher than 86°F (30°C) breed females—and more and more females are hatching. Although this would appear to skew the population demographics, Burke said that isn’t the case. Ironically, having more female hatchlings could help the population survive. “One male is all it takes to fertilize a lot of females,” Burke said. Even with a small number of males—take a ratio of 10 females to one male, for example—the population would still be fine, he explained.

The real issue is that climate change in the Northeast is causing drier conditions—which is deadly for terrapin nests. Even nests that escape the paws of raccoons are at risk of drying out during drought periods because eggs are porous and need moisture to keep hatchlings alive, Burke explained. Summer 2022 was especially harsh, he said, adding that he suspects very few hatchlings survived.

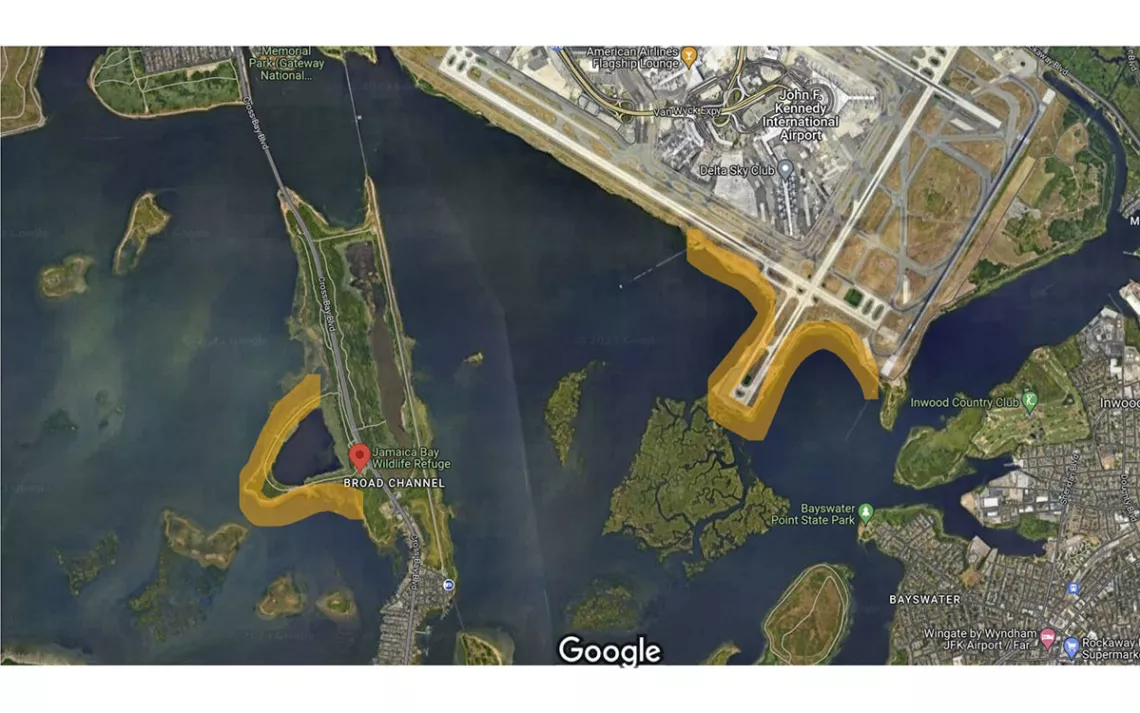

Two terrapin nesting populations live at Jamaica Bay: West Pond, which sits on an island of the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge called Ruler's Bar Hassock, and the John F. Kennedy International Airport runway, which is managed by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Scientists aren't sure why the JFK population is doing better than the one at West Pond, which mostly has old, female turtles—the Golden Girls, as Kanonik calls them. | Map courtesy of Google Maps; illustration by Marlowe Starling

As a keystone species, diamondback terrapins are crucial to the ecosystem. They eat small invertebrates, keeping those populations in check; they help transport nutrients from the bay to the shoreline, which fertilizes plants like native beachgrass; and they disperse seeds by eating plant material and pooping it out elsewhere.

But beyond the West Pond population's ecological benefits, if it disappears, so will New York City’s most accessible terrapin population to the public: an education tool and a way for residents to connect with nature in an urban landscape. “It's rare to have a population that is so easily viewable and accessible for the public,” Kanonik said. “New Yorkers generally don't know that there's a turtle nesting population here.” In the summer, Burke added, it’s especially cool to see terrapins nesting on the banks just beside the trails at Jamaica Bay. “In my years working there, I have again and again turned the corner on the trail and seen a gathering of people with binoculars and spotting scopes,” he said. “When you don’t have very many terrapins, you’re not going to see that. It just doesn’t happen anymore.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club